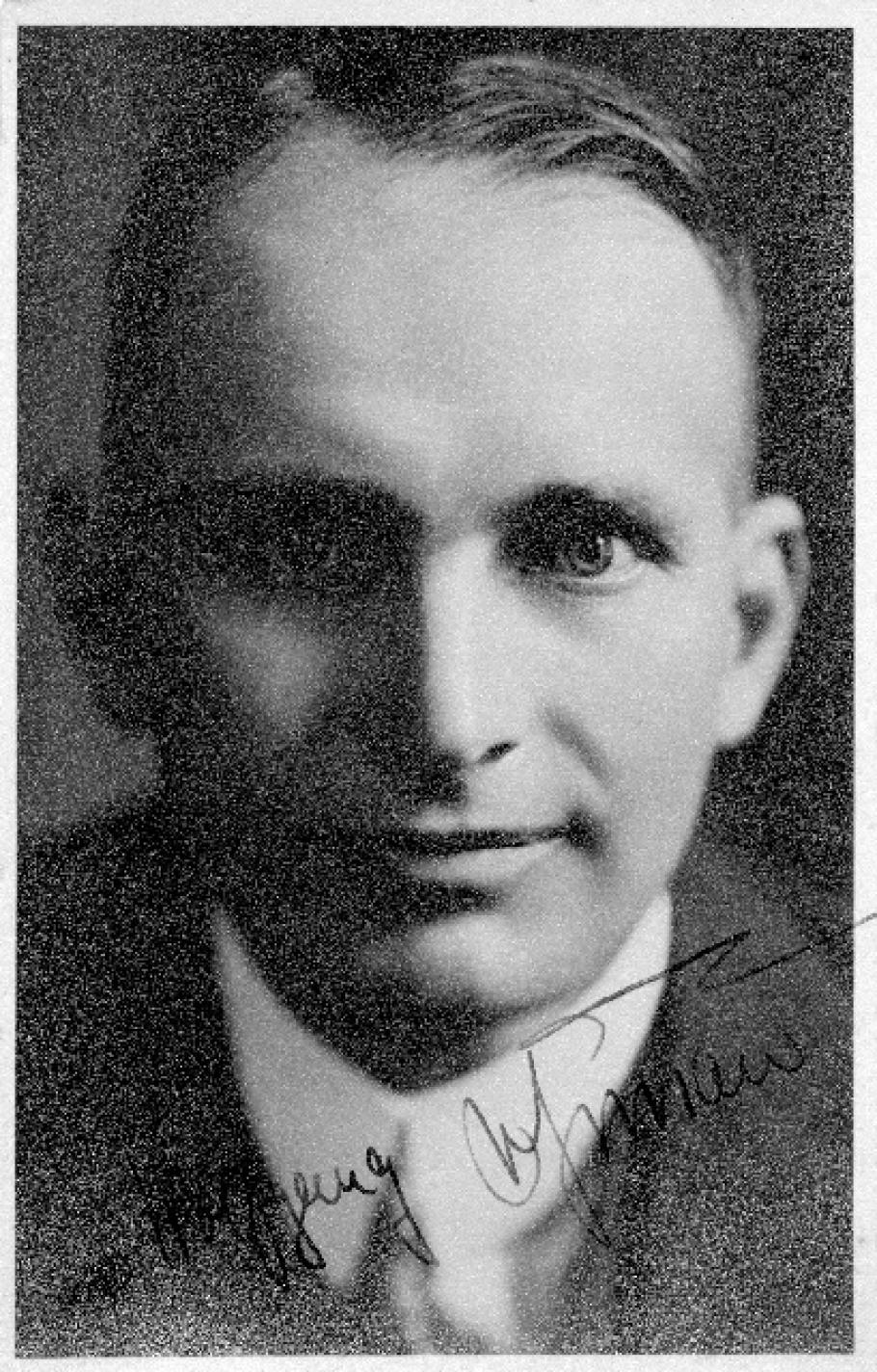

Wolfgang von Gronau and his Greenland “whales”

Aug 27, 2013

By Roger Connor

With the depredations of Nazi Germany dominating the international memory of the middle decades of the twentieth century, many German social, cultural, and technical contributions not associated with the tainted influence of the Third Reich have been forgotten or overlooked. One of the individuals who contributed significantly to the prospects of regular transatlantic air service before open warfare ended such endeavors was Wolfgang von Gronau. Between 1930 and 1932, von Gronau undertook a series of flights in Dornier Do J Wals (“whales”) that did much to determine the viability of using Greenland as a way station on aerial North Atlantic routes, particularly for flying boats. Von Gronau began his aviation career in World War I as a naval aviator who quickly rose through the ranks. By the end of the war, he was adjutant to the commander of aviation in the German high seas fleet and had introduced a number of innovations for German flying boats and floatplanes. In post-war Germany, he found a niche in commercial aviation. By 1926, he headed the Lufthansa seaplane school on the island of Sylt in the North Sea. Von Gronau took the opportunity in that role to begin considering the form of transatlantic commercial air service. His aircraft preference was for Dornier flying boats, particularly the Do J Wal, which had already established a reputation for reliability and ruggedness in harsh long-distance flights. Von Gronau began exploring routes to Iceland from northwestern Europe as part of his training exercises. The German government appeared ambivalent about this type of effort. Germany’s airship program and pioneering Lufthansa commercial services were bringing the nation much-needed prestige at a difficult time and authorities were likely reluctant to encourage risky endeavors that could call German equipment or personnel into question. Von Gronau’s airplane had a remarkable history. Polar explorer Roald Amundsen had escaped death in it during a failed attempt to reach the North Pole in 1925. It was also the aircraft in which Irish aviator Frank Courtney had nearly perished in while adrift in the middle of the Atlantic after an engine fire in 1928 (it was ultimately destroyed in a 1944 Allied bombing raid against Munich that leveled the Deutches Museum). By 1930, the American media was abuzz with speculation on whether von Gronau was likely to utilize Greenland as a way station for a transatlantic flight to the United States. The reason for the interest was uncertainty over the reliability or practicality of commercial air service across oceans.

While Charles Lindbergh and a number of other pioneering aviators had flown the Atlantic in the previous eleven years, prospects for oceanic commercial airplane service still appeared remote. Lindbergh’s continuous and exhausting thirty-three and a half hours in the air were not a viable option for large commercial transport aircraft. The shorter arctic great circle routes had the advantage of providing a more affordable route with stopovers in Canada, Greenland and Iceland. However, Greenland was a significant challenge. While the sparsely-populated Danish territory had seen some exploration by air, including by the U.S. Navy in 1925, it lacked suitable facilities for supporting landplanes. No one knew enough about the coast to judge the safety of flying boat operations on the southern coast and the weather was exceptionally unpredictable and often extreme. However, the success of the Graf Zeppelin in circling the globe as a herald for global commercial service during 1929 placed Germany at the center of North American and European hopes for reliable air transport between continents. It was in this context that von Gronau’s flights generated excitement, especially as the massive twelve-engine Dornier Do X airliner appeared to be preparing for its first demonstration of transatlantic passenger service. In August 1930, von Gronau reached Greenland from Iceland and then flew to Nova Scotia where officials greeted him and his three crewmembers with great enthusiasm for making the first complete transit of the northern transatlantic great circle route since the U.S. Army Air Service around-the-world flight of 1924. The essential difference between von Gronau’s flight and the Army flight was that the latter had a massive logistical effort behind it, whereas von Gronau improvised his arrangements. This included scavenging fuel from stores left behind from Swedish pilot Albin Ahrenberg during his successful rescue of British scientist Augustine Courtauld from Greenland’s interior three months earlier.

Von Gronau continued on to New York City, arriving on August 26 to even greater acclaim. A little over a week later, President Hoover invited him to the White House. Von Gronau attempted to wave off the attention, arguing that it was principally a training flight (one of his crewmembers was a pilot cadet). The lack of clear (or at least public) German government support allowed advocates for DELAG, the German airship corporation, the opportunity to disparage von Gronau. Graf Zeppelin captain Ernst Lehmann argued, “it proves nothing; in the first place, because the northern route is hopeless most of the year on account of fogs, and secondly I don’t believe planes are adapted to these long hops. It is asking too much of a motor, as numerous failures in the past prove.”

Ultimately, Lehmann was partially right. The German government continued its preference for transatlantic airship service through the 1930s until the Hindenburg disaster in 1937. The Dornier Do X did indeed make a transatlantic flight beginning in 1930, but it was a debacle in which significant accidents and mechanical trouble disrupted almost every leg of the flight resulting in a ten-month voyage to New York. With the poor showing and the Depression descending to its depths, the Do X was a hopelessly expensive leviathan that made even rigid airships appear profitable. By the time transatlantic airplane service became economically viable in the late 1930s, aircraft performance had increased to the point that stops in Greenland were no longer necessary and direct hops from Labrador to Ireland and back were possible.

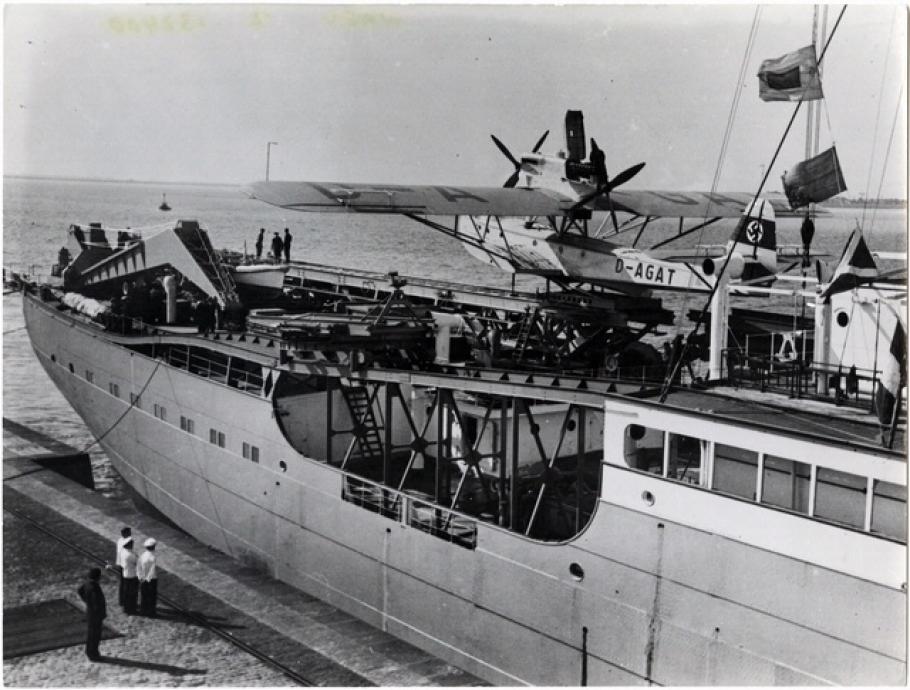

Nonetheless, von Gronau’s 1930 flight, along with a repeat flight in 1931 and an around-the-world flight in 1932 (both with a new Wal he called the “Greenland Whale”), revealed several key considerations in northern transatlantic service. First, and foremost, was the issue of weather. The weather near Greenland was remarkably unpredictable and could be disastrous if it obscured suitable landing sites with fog. Von Gronau singled out the lack of reliable meteorological data as one of the largest obstacles to regular air service. In terms of navigation, von Gronau felt that the unpredictability of the weather in this region made reliance on celestial navigation impractical and suggested that construction of a network of radio navigation beacons would be essential to reliable air service. His vision did come to form but only during World War II when the Army Air Forces Air Transport Command and other agencies established significant navigation and meteorological facilities in Greenland, including LORAN stations, that were critical to supporting the movement of aircraft to Europe during the war. One other outcome of von Gronau’s 1930 flight was that it was another nail in the coffin of Edward Armstrong’s “seadrome” project of building floating airfields strung across the Atlantic every 375 miles. The simple expedient of improvising new landing or harbor facilities in Greenland was a far more economically viable option than spending billions on offshore platforms at a time when the Depression had radically constrained government spending. The Dornier Wal’s eventual role in commercial transatlantic flight was small, but significant. In mid-1933, Lufthansa began to evaluate the aircraft for shortening mail service across the South Atlantic by using “catapult ships.” Crossing the South Atlantic even at its shortest distance, between Bathurst (Gambia, Africa) and Natal, Brazil, would still have meant more than 3,000 kilometers, and about eleven hours flying time. By using a freighter as catapult ship, Lufthansa broke this distance into shorter legs, and helped pilots with navigation. After successful trials in 1933, Lufthansa established a regular service in 1934 with the former freighter “Westfalen,” stationed west of Bathurst in the South Atlantic as a floating relay station and radio navigational beacon. Mail arrived from Germany via Stuttgart-Böblingen, Seville, Las Palamas de Gran Canaria, and then to Bathurst. A Dornier Wal took the mail to the “Westfalen.” There, the Wal made a water landing and the ship’s crew hoisted it aboard for maintenance, refueling, and catapulting towards South America. Soon, a second ship, the “Schwabenland,” was stationed near Fernando de Noronha. By the end of 1934, Lufthansa had four Dornier Wal flying boats in regular service in the South Atlantic, with one flight in each direction per week.

Von Gronau’s flights of the early 1930s established him as one of the nation’s premier aviators (and perhaps its best long-distance air navigator), allowing him to become an undersecretary in the air ministry in 1933 and, subsequently, president of the German Aero Club. His ambivalence for Nazi leadership resulted in something of a self-imposed exile as air attaché in Germany’s Tokyo embassy on the eve of World War II where he served out the remainder of the war. Post-war he became a technical advisor to Lufthansa as they developed their transatlantic service – though with landplanes rather than flying boats.

Related Topics

You may also like

Related Objects

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.