The fact that transportation was a segregated business in the American South for many decades of the twentieth century is well known. Many older African Americans who grew up in the South painfully remember the time when black passengers had to sit in the back of busses or use separate train compartments; and when train stations and bus terminals provided separate but mostly unequal facilities such as drinking fountains, restrooms, waiting lounges, and eating facilities for black and white passengers.

Most people I talk to about my research are surprised to learn that segregation laws also regulated access to air transportation well into the post-war period. While African American travelers enjoyed free and unrestricted access to the aircraft cabin, and the airlines, as federally regulated businesses for the most part, provided non-discriminatory services to all passengers, many airports across the South subscribed to so-called Jim Crow practices. Studies conducted in the mid-1950s by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Congressman Charles Diggs, a Democrat from Michigan, showed that in fact the vast majority of Southern airports provided duplicate waiting rooms, restrooms, and dining facilities in order to separate the races in their use of airport terminal space. To many critical observers such as Diggs it seemed absurd that travelers who were en route to enjoy the most modern means of transportation – the airplane – had to subject themselves to the humiliating experience of having to pass through segregated terminals. Local municipalities, in charge of airport management, in most instances ruthlessly enforced segregation claiming local laws or local customs as the basis for their actions. Eager to preserve the South’s system of institutionalized racism, mayors and airport managers in places such as Jackson, Mississippi, Montgomery, Alabama, and New Orleans, Louisiana, resisted change. They saw no contradiction between the shiny exteriors of their newly constructed modern terminals and the datedness of the rules that structured their use.

Opposition to airport segregation began to express itself as early as the 1940s, when National Airport in Washington, DC became a target. To many observers it was a particular embarrassment that foreign dignitaries had to pass through segregated spaces at a facility which not only served as the gateway to the nation’s capital but was run by the federal government. The fact that at the time the District of Columbia still practiced segregation did not alleviate the criticism but rather enforced it. Civil rights organizations like the NAACP demanded that something be done and supported Helen Nash’s lawsuit against the airport in 1948. While the courts deliberated the merits of her case, which would ultimately go nowhere, the Administrator of Civil Aeronautics, the head of the federal agency responsible for the regulation of aviation and the administration of the country’s only federally-owned airport, stepped up his act and ordered the integration of the airport by way of amending the Washington National Airport Act in December 1948. Considered a bold regulatory move at the time, it ended discrimination at National Airport and enabled travelers to enjoy terminal services without “segregation as to race, color, or creed.”

Due to the special ownership structure at National Airport, the case could not be used to force airports elsewhere into compliance with the government’s new anti-segregation policy. Instead, the fight against airport segregation had to be fought on a case by case basis. It involved different actors: civil rights organizations, individuals, and federal agencies. And it relied on various strategies: direct action, litigation, and statutory reform. The airport in Atlanta was one of the first airports to be hit by direct action in 1959. Protesters had appeared before city councils and airport authorities. But until then none had staged protests in the locations where black air travelers experienced discrimination. The Atlanta Airport protest was organized by The Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) and is best described as an eat-in. It was carried out by an interracial group of activists who went to the segregated Dobbs House restaurant on August 8, 1959 to have lunch together. Unable to receive service for all members of the group they shared the meals they were able to buy and were asked to leave by the airport management thereafter. Although the protest did not lead to the immediate integration of the airport, James R. Robinson, CORE’s executive secretary, encouraged others to imitate it in an interview with the Cleveland Call and Post on August 8, 1959: “We all agreed,” he said, “that it was the best coffee we had ever had – the extra tang of drinking your coffee interracially across the Georgia color bar is highly recommended!”

Over the course of the next two years, more airports were targeted by direct action campaigns: CORE staged a “prayer pilgrimage” at the Greenville Airport in South Carolina; a group of CORE Freedom Riders targeted the airport in Tallahassee, Florida; students from the local colleges staged a protest at the Raleigh-Durham Airport. As a result of the protests, all three airports were desegregated.

Direct action protest was flanked by efforts to challenge segregation in the courts. The NAACP had long championed litigation as an effective road to integration and helped plaintiffs bring suit. This resulted in a number of individual damage suits against airport administrators and airport restaurants filed during the 1950s. But litigation was a slow and tedious process that moved from case to case. With an urgency that increased in the late 1950s and early 1960s civil rights leaders also tried to put pressure on the federal government and its regulatory agencies. They demanded the enforcement of existing anti-discrimination provisions in the Federal Airport Act and otherwise called for statutory reform. The Civil Aeronautics Administration, subsequently organized as the Federal Aviation Administration, was slow to react but eventually joined the fight against Jim Crow practices. Its attention focused on the Federal Aid Airport Program, a grant-in-aid program designed to subsidize airport construction across the country, as a way of preventing the construction of segregated airport facilities.

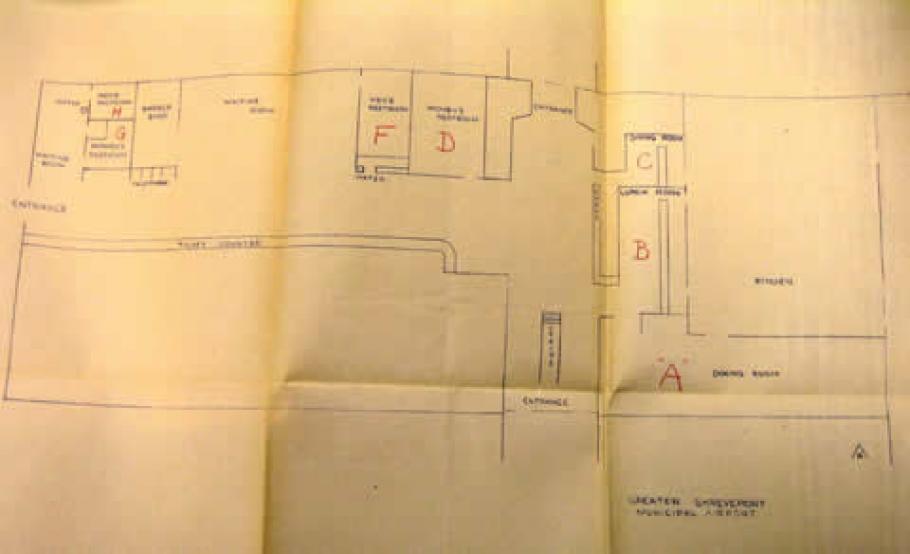

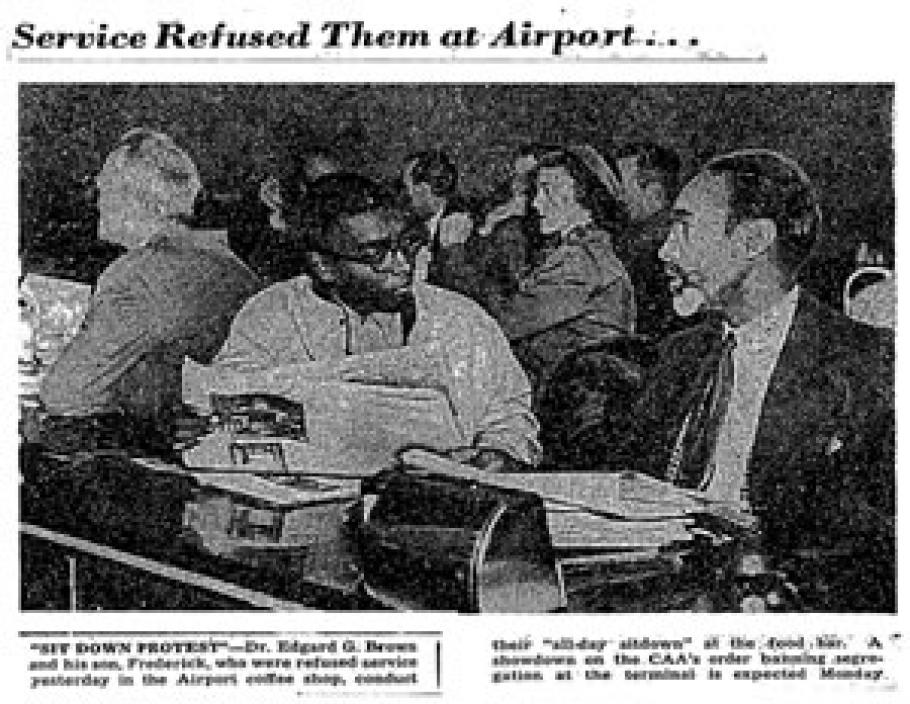

Finally in the early 1960s, the Department of Justice weighed in. In 1961, it initiated law suits against the airports in Montgomery, Alabama, and New Orleans. The following year, it filed actions against the airports in Shreveport, Louisiana and Birmingham, Alabama. In the leading case against Montgomery, the Justice Department produced testimony, images, and floor plans to prove that the airport management and the restaurant proprietor had systematically discriminated against black travelers by posting signs and segregating along racial lines the airport’s waiting, eating, drinking, and restroom facilities. The court ruled in favor of the government in January 1962 and ordered the integration of the airport. The case served as the precedent upon which the other cases were decided. Shreveport was the last airport to be forced into compliance. Losing its appeal against court ordered integration, the last signs at an American airport leading travelers to segregated facilities were ordered to come down on July 10, 1963.