The World Wasn't Ready for Nuclear-Powered Bombers

Mar 20, 2025

By Robert Bernier

The dangers of powering military aircraft with nuclear energy.

Seventy years ago, on September 17, 1955, a modified Convair B-36 departed Carswell Air Force Base in Texas. Legendary U.S. Air Force test pilot Fitzhugh L. “Fitz” Fulton Jr. was in the cockpit. Fulton would fly the heavy bomber 460 miles west to Roswell, New Mexico—and, in doing so, he made history.

Though the flight appeared to be routine, Fulton was, in fact, flying a top-secret mission that day. Unknown to the population below, his aircraft—which had been redesignated as the NB-36H Crusader—was emitting radiation along its entire flight path from Texas to New Mexico. The source of the radiation was an unusual payload in the aft bomb bay: a 35,000-pound, one megawatt nuclear reactor built by General Electric.

Also known as the Nuclear Test Aircraft, the NB-36H—its tail marked by the ubiquitous 1950s radiation symbol—was the world’s first flying nuclear reactor. The NB-36H would make an additional 46 test flights through March 1957, logging 215 hours of flight time, during which the reactor was operational for 89 hours. The reactor could be winched aboard from an underground pit before a flight, then lowered back underground postflight for storage between hops.

The ultimate objective of the risky flights was to lay the foundation for the Air Force to build a nuclear-powered bomber. At the time of Fulton’s flight, though, the air-cooled nuclear reactor didn’t propel the bomber—or power any of its systems. The reactor was aboard solely to test shielding that would protect the flight crew from exposure to nuclear radiation and to study the effects of said radiation on aircraft systems.

Despite the Air Force’s enthusiasm for a nuclear-powered strategic bomber—an eagerness described by retired nuclear engineer Bill Jones as “unbridled enthusiasm”—many physicists of the time, among them J. Robert Oppenheimer, thought the idea of nuclear-powered flight “perhaps bordered on lunacy” given the technology then available. The physicists were right. The project would prove to be one of the most technologically challenging military programs ever undertaken, one that would involve major industrial companies and research laboratories throughout the country. The 10-year quest to build a nuclear-powered bomber would consume nearly $1 billion of government funding (equal to $12 billion in today’s dollars).

Adding to the formidable technological challenges, the Nuclear Test Aircraft program was dogged by political squabbling and fragmented management. “It’s understandable why the military would find this idea attractive, unfortunately it was never practical,” says Stephen Schwartz, an independent nuclear expert who previously led the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Cost Study Project at the Brookings Institution in the 1990s. “But that didn’t stop the military from trying.”

The power of the atom

Postwar United States was a confident United States, a country capable of anything, with a huge industrial base and money to spend. American scientists and engineers dreamed big: Atomic power would be employed to generate dirt cheap electrical power, desalinate the world’s oceans for drinking water, and power ships and aircraft, among other ambitious schemes.

“There was a technical optimism around all things nuclear after World War II,” says Schwartz. “And there was also a strong desire on the part of many who worked on nuclear weapons to find something beneficial and constructive to nuclear energy as opposed to destructive.”

In 1957, a nuclear physicist studied alpha rays in a continuous cloud chamber to obtain information aimed at minimizing the undesirable effects of radiation on nuclear-powered aircraft components.

Strategic planners during the Cold War saw nuclear energy as a way to safeguard the U.S. against a Soviet first strike that could be carried out while U.S. Air Force bombers were still on the ground. A fleet of nuclear-powered bombers, they believed, could patrol the skies for days or even weeks. “If you needed to keep airplanes airborne as a deterrent, a nuclear-powered aircraft would give you the ability to do that without aerial refueling,” says Michael W. Hankins, an aeronautics curator at the National Air and Space Museum. “So, that gives you a lot of advantages.”

Such aircraft, if successfully developed, would possess tremendous range and endurance, and they wouldn’t need vulnerable forward air bases from which to operate. Atoms were the future! A study commissioned by the Atomic Energy Commission and conducted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology confirmed that nuclear flight was possible. But the study also warned—prophetically, it would turn out—that such aircraft would likely be made obsolete by newer technology.

General Electric’s Heat Transfer Reactor Experiment 3 was a direct air cycle engine where air from the turbojet’s compressor was routed through the hot reactor core. Designed to generate up to 35 megawatts, it could potentially power two J47 engines for 64 continuous hours.

Still, to the Air Force, the appeal of nuclear-powered flight was thought to trump its disadvantages. The military had begun investigating the idea in 1946 and, in 1951, the Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission created the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion (ANP) program. Experienced airframe and engine manufacturers such as Convair, Lockheed, General Electric, and Pratt & Whitney were soon enlisted in the effort, along with research facilities that included the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee and the Idaho National Reactor Testing Station.

A major challenge confronting engineers was the energy conversion problem—transforming the intense heat created by a nuclear reactor into mechanical energy. A successful system would consist of a reactor powering a thrust-producing engine, but in a combination light enough to be carried aloft in an aircraft, a tall order for the technology back then.

Two types of reactor-engine combinations were considered. General Electric was tasked with developing a direct air cycle engine. Air from the turbojet’s compressor was routed through the hot reactor core, then through a turbine, before being expelled from the tailpipe at high velocity. The direct air cycle engine reactor combination promised better performance and simplicity. This type of engine would, though, leave a trail of radioactive exhaust in its wake.

Pratt & Whitney pursued an indirect air cycle arrangement for which air from the engine’s compressor did not go through the reactor core but instead was routed through an intermediate heat exchanger plumbed to the reactor, then through a turbine and out the exhaust nozzle. This configuration was much kinder to the environment, but far more complicated.

While engineers and program managers were debating reactor-engine configurations, it was decided that a flying testbed was needed to see if getting a functioning nuclear reactor airborne was even feasible.

Thankfully, a tornado arrived.

Winds of change

Air Force strategists worried that a Soviet first strike could wipe out U.S. bombers while they were on the ground. Mother Nature confirmed their fears when, on Labor Day in 1952, a string of tornados ripped through Carswell Air Force Base, destroying or incapacitating two-thirds of Strategic Air Command’s fleet of B-36 heavy bombers.

The NB-36H was outfitted with a lead-encased cockpit to protect the flight crew from radiation exposure.

It took three months to repair the aircraft, but one of the damaged B-36 “Peacemakers” was destined for greater things: It was selected for conversion to a flying nuclear laboratory, redesignated as NB-36H. The aircraft, with its 230-foot wingspan and impressive maximum takeoff weight of 410,000 pounds, was powered by six large piston engines, in a pusher arrangement, along with four General Electric J47 jets mounted on pylons. Often described as having “six turning and four burning,” the Convair bomber was just the sort of airplane that could take flight with a nuclear reactor—and literally tons of protective shielding.

The nose section of the NB-36H, which had been damaged by the tornados, was removed and replaced with a lead- and rubber-lined cockpit section weighing nearly 12 tons. A water barrier was installed behind the cockpit to absorb radiation from the reactor, which was located in the aft bomb bay, as far from the crew as possible. The five-person crew consisted of a pilot, co-pilot, flight engineer, and two nuclear engineers.

The U.S. Air Force faced intense political pressure to complete a nuclear-powered bomber after the U.S. Navy’s successful launch of its first nuclear sub, the USS Nautilus.

The Air Force was facing mounting pressure to get something into the sky following the U.S. Navy’s 1954 triumph in launching the USS Nautilus, the world’s first operational nuclear-powered submarine. During its shakedown cruise, the Nautilus had “oohed” and “ahhed” the American people. Capable of traveling submerged beneath the world’s oceans at full speed without ever refueling, this was the sort of wonder everyone had come to expect from the atomic age.

Members of the U.S. Congress had high expectations as well. In early 1955, the joint Congressional Atomic Committee convened a special session while aboard the Nautilus—voyaging 300 feet below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean—where, according to a newspaper report, they ordered the Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission to “stop dawdling” and “speed up the development of nuclear-powered aircraft.”

The committee blamed the delay on mismanagement. “They have let contracts for this purpose, but there is little or no coordination and supervisory responsibility of the kind that created the Nautilus,” they said. They weren’t wrong. While the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion program encompassed numerous government agencies and private contractors, the Navy’s atomic submarine initiative had come to fruition through the strong and focused leadership of Admiral Hyman Rickover. Still, the two programs faced very different technological challenges. It had been much easier to accommodate the weight of protective shielding in a submarine than carrying it aloft in an aircraft.

Nonetheless, the Navy wasn’t shy in suggesting that maybe the Air Force “should leave it to us,” and it’s not like Navy leadership didn’t have airborne aspirations of their own. In 1953, the Navy had awarded contracts to Convair and Martin to investigate adapting Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion technology to flying boats, while also looking into atomic-powered early-warning airships to protect against a surprise enemy first strike.

Commander Arthur Struble, writing in the November 1957 issue of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings, argued that flying boats would be ideal for nuclear propulsion: “By confining flights to ocean areas, the radiation and contamination hazards to populated and industrial areas can be reduced.”

The Air Force was all too aware of the risks of flying over land. Concerned about possible accidents during takeoff and landings, the reactor was activated only when the aircraft was at cruising altitude. Flights were conducted over remote and sparsely populated areas of west Texas and New Mexico. With the possibility of airplane accidents, local first responders were informed of impending test flights so that (if the need arose) they could keep lookie-loos away from radiation-contaminated crash sites.

During test flights, the Convair NB-36H (foreground) was accompanied by a Boeing B-50, staffed by technicians who monitored the experimental aircraft’s radiation emissions.

During its flights, including the Fitz Fulton mission in September 1955, the NB-36H was closely followed by a Boeing B-50 carrying technicians who could monitor radiation emissions. A Fairchild C-119 transport was also part of the procession, flying with a team of gung-ho parachutists (waggishly dubbed the “glow in the dark squad”) ready to jump onto a crash site to secure the area.

The NB-36H flew its final test flight in 1957. The Air Force had demonstrated that a nuclear reactor could be safely operated aboard aircraft—barely. The weighty shielding to protect the crew from radiation made the future of crewed nuclear aircraft doubtful.

Reporter Blair Justice summed up the dilemma in a September 1956 Daily News article: “It would be possible to build an entirely safe atomic airplane that would be too heavy to get off the ground. To make it safe and make it fly is the Air Force’s problem.” Still, the project continued. Another modified B-36, designated the X-6, was to be equipped with four X-39 nuclear-powered engines grafted onto its belly beneath the reactor. Though the X-6 was canceled, development work continued on nuclear-powered engines. General Electric successfully operated its X-39 engines (J47 turbojets configured to run on nuclear energy) on a ground test stand in 1956.

Red Menace

Despite the ongoing failure to get a nuclear-powered bomber into the sky, the program was kept aloft by growing alarm about the Soviet Union’s technological prowess following the surprise launch of Sputnik on October 4, 1957.

The panic only increased when the influential Aviation Week published an article in 1958 titled “The Soviet Nuclear-Powered Bomber,” which argued that the Soviets had leapt ahead and were well into the process of flight-testing a fully operational nuclear bomber. “Once again, the Soviets have beaten us needlessly to a significant technical punch [due to] technical timidity, penny pinching, and lack of vision that have characterized our own political leaders,” wrote Aviation Week’s editor, Robert Holtz.

Says Schwartz: “Our program was in part spurred on by what we thought the Soviets were doing.” The alleged Soviet bomber even found its way onto toy shelves when Aurora, a maker of plastic models (see “Some Assembly Required,” Summer 2022), quickly capitalized on the Aviation Week story by producing a kit with box art that depicted a menacing delta-wing bomber flying over Red Square.

The contents of the Aviation Week article matched details in classified intelligence reports—including a briefing that had given the purported Soviet nuclear bomber the codename Bounder—which has led aviation journalists and historians to surmise that the information was strategically leaked to boost support for the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion project. “I’m sure they were convinced at the time,” a longtime Pentagon correspondent commented decades later in the Washington Post. “But it makes you wonder who convinced them.”

Since 1954, the Air Force had been working on a supersonic nuclear-powered bomber program labeled WS-125A without success, and in 1958, it tried again with a less ambitious bomber proposal—and nifty new acronym—called CAMAL (continuous airborne alert, missile launching, and low-level penetration). Convair won the contract with its futuristic-looking subsonic NX-2 equipped with four GE nuclear-powered engines.

That same year, General Electric had achieved another significant milestone: running its X-39 engines on nuclear power for 64 continuous hours. David Shaw, head of GE’s Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion department, announced to professional engineering gatherings in early 1961: “We have reached the point that we can say that when an airframe is ready, we can have the nuclear direct-air-cycle powerplant ready for installation.” Well, maybe. The X-39 engines could run on nuclear power while mounted on an enormous ground test-stand located at a test facility, but they were far from flight ready.

The projected NX-2 bomber would have been a behemoth, capable of staying airborne for days, even weeks. Shielded crew quarters were planned with a galley, bunks, lavatory, laundry bins, and hi-fi entertainment for the crews’ use during their anticipated long aerial patrols. Menus were drawn up for the galley, and some news stories anticipated the heavy NX-2 would operate from a 23,000-foot runway. The Air Force began construction of the NX-2 air base adjacent the remote, sparsely populated Idaho nuclear engine test site where technical support was available in case of an accident.

But it was not to be. By the end of the decade, enthusiasm for the project had waned, and thoughts of nuclear-powered aircraft flying overhead and possibly crashing had alarmed both the public and government officials. Doubters within the Pentagon canceled the NX-2 program in 1959.

The Soviet Union, meanwhile, hadn’t made any significant progress either. Moscow had envisioned fleets of nuclear-propelled flying boats that could transport 1,000 passengers at unheard of speeds. In 1955, determined to build their own nuclear-propelled bombers, the Soviets modified the largest bomber they had, a four-engine turboprop Tupolev Tu-95 (NATO codename Bear) to fly with a nuclear reactor on board.

Like the American NB-36H, the Soviets’ flying laboratory was not propelled by nuclear power. And, like the Americans, the Soviets eventually concluded that nuclear aircraft were impractical. Says Schwartz: “It’s fundamentally a problem of the shielding. There’s so much weight required to keep the reactor from killing the crew, that it’s too heavy. It can’t fly anywhere.”

Over and out

The shielding issue was never adequately solved by either side. In an attempt to skirt the weight impasse and keep the program alive, some diehard Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion proponents suggested that nuclear-propelled bombers should be crewed by a cadre of older aviators who would likely die of natural causes long before succumbing to radiation poisoning. The draconian proposal would have reduced the amount of shielding required, making the bombers significantly lighter.

But the old guys never got the chance, because by 1961, great strides had been made in the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles, which made further spending on nuclear-powered aircraft not worth the effort.

Upon taking office in 1961, President John F. Kennedy took a look at the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion program with fresh eyes and decided to cancel it. Kennedy stated in a national security report: “Nearly 15 years and about $1 billion have been devoted to the attempted development of a nuclear-powered aircraft; but the possibility of achieving a militarily useful aircraft in the foreseeable future is still very remote.”

A report published by the General Accounting Office was even more brutal: “The ANP program has been characterized by attempts to find short cuts to early flight and by brute force and expensive approaches to the problem. Thus we find that only a relatively very small fraction of the funds and energies applied to this program has gone into trying to develop a reactor with a potentially high performance.... As a result, we are still at least four years away from achieving flight with a reactor-engine combination, which can just barely fly.”

The new president redirected U.S. scientific efforts toward the race to the moon. At NASA, scientists who studied the feasibility of nuclear-powered rocket engines made use of research conducted by the ANP program. Robert Deissler, a scientist at what is now known as the NASA Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, told a NASA historian in 1991: “The fact that nuclear propulsion never quite materialized as a viable scheme did not lessen the value of the research, which aided in understanding heat transfer in a variety of situations.”

Indeed, NASA’s Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application program continued until 1973, when it fell prey to post-Apollo program budget cuts. But NASA’s space nuclear propulsion office continues to explore the concept—most notably, a joint project with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency that aims to test a nuclear-powered rocket in space as soon as 2027.

Despite great effort, the U.S. never did field a nuclear-powered bomber. “There were just too many technical hurdles to get over, and past what was state of the art at the time,” notes Hankins. “And the cost, the cost on top of that, these things would have been just too expensive.”

Even if the technological issues could have been overcome, the bomber would have had a more difficult time overcoming public uneasiness, says Bob Hartman, who formerly served as a reactor operator aboard nuclear-powered submarines “It’s hard enough convincing people you want to put a nuclear powerplant near their house in a giant concrete building,” he says. “Try telling them you want it flying around their city.”

Robert Bernier is a former U.S. Navy aviator and commercial pilot now working as an aircraft restoration volunteer at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.

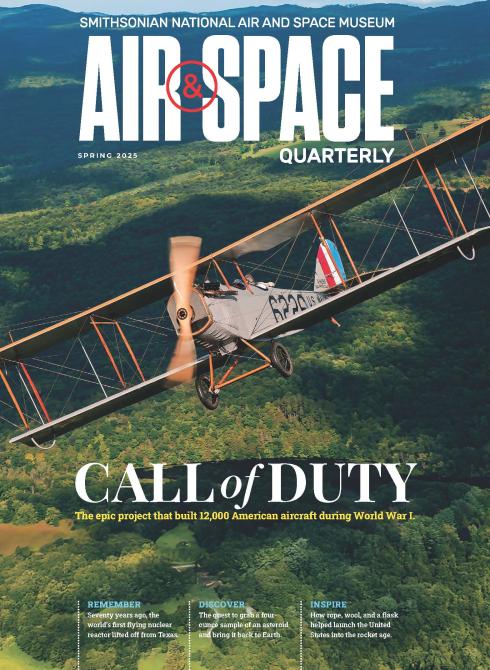

This article, originally titled “Up and Atoms,” is from the Spring 2025 issue of Air & Space Quarterly, the National Air and Space Museum's signature magazine that explores topics in aviation and space, from the earliest moments of flight to today. Explore the full issue.

Want to receive ad-free hard copies of Air & Space Quarterly? Join the Museum's National Air and Space Society to subscribe.

Related Topics

You may also like

Related Objects

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.