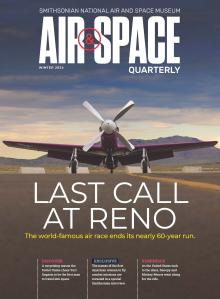

Last Race at Reno

Dec 20, 2023

By Preston Lerner | Photography by Chad Slattery

The world-famous event ends its 60-year run with excitement, nostalgia, and tragedy.

Six decades—that’s how long they’ve been racing in Reno, Nevada. Six decades of outrageous speed. Six decades of remarkable innovations. Six decades of gut-wrenching calamities. Clay Lacy remembers how it all began.

Now 91, Lacy is one of the most celebrated aviators in history, a pioneer in the field of air-to-air photography and the holder of dozens of speed records. In January 1964, however, he was just “flying the line” for United Airlines. When a snowstorm stranded him in Reno, he happened to see an advertisement for an air race the following September. It was the first race to be held since a fatal crash at the National Air Races in Cleveland, Ohio, 15 years earlier, and he immediately started making plans for the fall.

“The Unlimiteds are the big dogs,” says Vicky Benzing, a pilot who flies Plum Crazy, one of several P-51s that came to Reno.

Lacy decided on a war-surplus North American P-51 Mustang as a cheap but competitive ride for the Unlimited race. When he got back to Los Angeles, he discovered that his friend, airplane dealer

Allen Paulson (the founder-to-be of Gulfstream American—now known as Gulfstream Aerospace), was selling a Cessna 310, and a guy in Idaho was looking to acquire it in a trade for his Mustang. “Allen told him, ‘Bring the P-51 down here and 10,000 bucks and you can have the Cessna,’ ” Lacy recalls with a wry chuckle. Today, you can buy a cherry 310 for $200,000, while flyable Mustangs start at more than $2 million.

“We couldn’t believe what was unfurling in front of us. It was just so magical to bring the days of Cleveland back in such grand style—except for the place where we had it,” said race announcer Sandy Sanders.

Back then, the races were held at Sky Ranch, a crude airfield 10 miles northeast of Reno that had been spruced up with grandstands rented for the occasion. The narrow dirt runway was so rocky that hotshot test pilot Darryl Greenamyer refused to land his Grumman F8F Bearcat on it and was disqualified for proceeding to Reno Municipal Airport. “It was just a dust bowl,” recalls Sandy Sanders, who announced the races.

Races were run on an 8.019-mile course marked by pylons made from painted 55-gallon oil drums affixed atop 50-foot-tall telephone poles. The championship race was won by Bob Love, a Korean War ace whose white P-51D, Bardahl Special, was modified with a high-performance, anti-detonation injection (ADI) system. But an odd scoring system and a time penalty for pylon cuts (flying inside the pylons) led to Love being demoted to second. Mira Slovak was declared the winner while Lacy finished third in Paulson’s Mustang.

Man O War, a P-51D (at right), battles Pretty Polly, a P-63C. Air racing is “unanticipated aerobatics, because the wake from a big airplane can roll you upside down,” says racer Alan Preston.

Thanks in part to support from local casinos, the event was a huge hit. “The wind blew, it was hot, it was dusty, and we didn’t give a sh*t,” says Sanders. “We couldn’t believe what was unfurling in front of us. It was just so magical to bring the days of Cleveland back in such grand style—except for the place where we had it.”

Two years later, the races moved to a more hospitable venue—the recently decommissioned Stead Air Force Base—and they’ve been held there every year since, excluding 2001 (due to 9/11) and 2020 (in response to COVID-19). But all good things must come to an end. When the Reno Air Racing Association (RARA) announced last March that 2023 would mark the final year of the National Championship Air Races in Reno, the press release was greeted with resignation.

A 1932 poster promotes the National Air Races in Cleveland, Ohio. After a fatal crash in 1949, the event went on hiatus until being revived at Reno in 1964.

Everybody had known for years that the event was running on fumes. Insurance premiums had skyrocketed ever since a P-51D Mustang crashed in 2011, killing the pilot and 10 spectators. Housing tracts and warehouse complexes encroached on what had been a remote outpost surrounded by sagebrush and rattlesnakes. Entries in the Unlimited class—the showcase for gleaming World War II-era fighters powered by sleek Merlin V-12s and massive American radials—were dwindling, as pilots became less inclined to risk their rare airplanes for meager financial rewards. Attendance was down. Enthusiasm was muted. In a world dominated by digital technology, the analog glories of air racing seemed quaint, if not entirely passé.

A North American T-6 Texan, Midnight Miss III, is parked near an appropriately named street.

But precisely because 2023 was billed as Final Flag at Reno, the turnout for race week was stronger than it had been in years—an estimated 140,000 fans and so much congestion it was hard to walk from A to B without being run down by a tow vehicle or a golf cart. Bringing the event full circle was the presence of two warbirds that had been featured at 1964’s inaugural Reno Air Races.

Lacy’s purple Mustang was back, lovingly restored as Plum Crazy and owned and piloted by airshow veteran Vicky Benzing. “I’ve flown in the Sport class, and I’ve flown in the Jet class,” says Benzing. “But the Unlimiteds are the big dogs.”

Alan Preston, three-time Reno air race champion reflects on the risks of air racing. “The airplanes themselves are dangerous. They are high-performance machines that were made either to go to war or to train people to go to war. We’re operating the same airplanes so we have exactly the same risks.”

The meanest of the big dogs was the white P-51D, Bardahl Special, which Bob Love piloted when he coulda, woulda, shoulda won Reno’s 1964 Unlimited championship. With air racing’s rock star—the handsome and remarkably congenial Steven Hinton Jr.—in the cockpit, Bardahl Special was the prohibitive favorite this year. But just hours before Hinton’s expected coronation as the winningest pilot in Unlimited history, the Reno Air Races ended prematurely.

At 2:15 p.m. Sunday, the final day of racing, there was a midair smash-up between a North American Aviation AT-6B and a T-6G, two loud and rugged World War II trainers that competed in a class of their own. The class’ defending champion and past champion Nick Macy collided with Chris Rushing after finishing first and second in the race and crashed short of the runway. They were the 22nd and 23rd pilots to die at Reno during the show’s 60-year run.

A highlight of the 2023 races was when a Korean War-era Grumman F8F Bearcat (below) flew formation with a Boeing F/A-18 Super Hornet in a tribute to U.S. Navy aviators.

Air racing just might be the most dangerous mainstream sport—several orders of magnitude more perilous than automobile racing. “The airplanes themselves are dangerous,” says longtime racer Alan Preston, who earned championship titles at Reno in three classes. “They are high-performance machines that were made either to go to war or to train people to go to war. We’re operating the same airplanes, so we have exactly the same risks. The difference is, back then, they had an acceptable loss rate. And we do not.”

Twenty-five years ago, Preston helped create the curriculum for a rookie school designed to mitigate the risks that are baked into air racing. “It’s low-level fast,” says Preston. “It involves what I call ‘uncooperative formation.’ It’s unanticipated aerobatics, because the wake from a big airplane can roll you upside down or just throw you out of the racecourse. And then the other factor is emergencies.” Inevitably, parts fail and mistakes are made, and it’s the nature of aviation that most serious accidents result in fatalities.

The easternmost section of the grandstands is the domain of the spirited orange-clad fans known as Section 3, who enjoy rating the day’s activities with scorecards. The group was founded more than 40 years ago.

Still, there’s no shortage of pilots willing to run those risks. This need for speed has encouraged RARA to seek new venues to keep air racing alive. Board chairman Fred Telling—a hardcore enthusiast (a veteran T-6 racer who owns one of three Mustangs that raced at Reno in 1964) and a high-powered businessman (he retired from Pfizer as a vice president)—says six locales have responded to a request for proposals to host air racing in 2025, if not 2024.

On September 16 at the 1982 Reno air races, fan Bob Lewis invited everyone to meet in section 3 of the spectator stands the following day, which marks the beginning of the group and explains why they still wear the number today.

Most racers seemed cautiously optimistic that RARA would find a new home for air racing. But they’re universally melancholy about what they’re leaving behind—the cinematic backdrop of mountains surrounding the airfield; the long, wide runways and largely empty airspace; and, most of all, the annual camaraderie of what they call their “September family.”

“It’s been a good, long, hard run, and it’s been fun,” says perennial Unlimited crew chief Larry Rengstorf, who in 1972 slept on a mattress in the back of a Pontiac Bonneville station wagon to attend his first race. “We’ve lost some good friends. We’ve even lost some enemies, you know?” He laughs as he runs his hand across his face. “We’ll miss it, that’s for damn sure. The other day, we were talking about something we forgot to bring. I said, ‘No sweat. I’ll put it in a checklist. I won’t forget it next year.” He shakes his head. “Next year? Oh, yeah, that’s right. Not here. Might be somewhere else. But not here in Reno.”

The 2023 event included a kid-size version of Dreadnought—a modified Hawker Sea Fury that has claimed Gold six times.

“Gentlemen, you have a race”

“Air racing fills a motorsports niche like hydroplane and powerboat racing,” says Jeremy Kinney, associate director for research, collections, and curatorial affairs at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, who attended the 2023 races in Reno. “It may not be the most popular nationwide in terms of visibility, but the dedication of the racers, owners, suppliers, and fans is infectious, and indicative of the lifetimes dedicated to the sport.”

The first air races were held in France in 1909, and the wildly successful Los Angeles International Air Meet was staged the following year. Some of the races during the ensuing decades left their mark on aircraft design. “The military air racers that flew in the Pulitzer and Schneider races in 1920s America and Europe reflected a desire to push aircraft development, which resulted in indirect and direct advances in aircraft streamlining and engine development,” says Kinney. “The Supermarine S.6B air racer and its Rolls-Royce ‘R’ engine, often hailed as the precursors to the Spitfire and Merlin of World War II, is a perfect example.”

During the Great Depression, ingenious homebuilts like the stumpy Gee Bees and the streamlined Wedell-Williams racers were faster than the military fighters of the day, and racing pilots such as Jimmy Doolittle and Roscoe Turner became national celebrities.

“The populist National Air Races of the 1930s in the United States reflected innovation for the sake of competition,” says Kinney, citing Turner’s iconic RT-14 Meteor as an example, as well as later aircraft, such as the “heavily modified World War II surplus fighters competing in the Unlimited class at the National Championship Air Races, including the former Bearcat Conquest I or the purpose-built Formula I racers like the Nemesis DR 90.” The relatively new Sport class, Kinney says, is a “great example of innovation driving design since that class exists to influence new designs and to see that implemented in homebuilt and production aircraft like Nemesis NXT.” (These four aircraft are part of the Museum’s collection.)

The National Air and Space Museum is home to several famous racing aircraft, including a Grumman F8F-2 Bearcat, Conquest I.

In the years before Reno, the National Championship Air Races in Cleveland drew tremendous crowds. More than 70,000 spectators were said to be in attendance on September 5, 1949, when a heavily modified P-51C rolled to an inverted position and augured into a house at 400 mph in the suburb of Berea. The pilot was killed along with the house’s occupants, a woman and her 13-month-old son. For a while, air racing died along with them.

Fifteen years passed before a wealthy Nevada cattle rancher and champion hydroplane racer named Bill Stead revived the sport. After the 1966 move to the current location at Reno-Stead Airport, Lockheed test pilot Darryl Greenamyer emerged as its first hero. Greenamyer enlisted Lockheed Martin Skunk Works engineers Pete Law and Bruce Boland to modify his Bearcat, enabling him to win six championship races in seven years. (Years later, Greenamyer’s Conquest I airplane would go on display at the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.) Lacy has the distinction of being the only pilot to beat Greenamyer during this stretch. After that, Greenamyer told Law: “You and Bruce have to go off and start helping the other guys.”

Greenamyer and Boland are both gone, but Law is still obeying Greenamyer’s command. On Friday, Law is perched on the wing of a Yak 3-U, contorting his 87-year-old frame inside the engine cover to tweak the anti-detonation injection system of the Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp R-2000. Law hasn’t missed a race since 1966. “It was love at first sight,” he says. “I love the engineering. I love the sounds. I love the people who own and race the airplanes.”

Steven Hinton Jr. holds court with fans. In 2009, at age 22, he became the youngest pilot to win Unlimited Gold at Reno.

Almost on cue, retired pilot Tom Dwelle walks up. “Tom! Tom!” Law fairly yells. “Long time! I’m going to wear my Critical Mass T-shirt tomorrow!”

Dwelle is one of dozens of racing legends who’ve returned to Reno this year to relive the glory days one last time before the event passes into history. Although he was a two-time champion in the T-6, Dwelle was never able to grab the Unlimited Gold with Critical Mass, a Hawker Sea Fury he upgraded with a Wright R-3350—an engine he learned to trust while flying the Douglas A-1E Skyraider on 270 fighter-bomber missions over Vietnam.

In 2000, Dwelle was outrun only by another fighter pilot who also saw action in Southeast Asia. Skip Holm is in the house, signing autographs and giving speeches. He’s better prepared today than he was during his first visit to Reno, in 1981. When a skeptic asked the rookie what he knew about air racing back then, Holm told him: “I raced two MiG-21s all the way across Laos to Hanoi.” Well played, sir. Despite his lack of warbird experience, Holm captured the Gold with Jeannie his rookie year and earned four more Golds flying two other P-51s.

Speedball Alice rounds a pylon. In the early days, races were run on a crude course marked by pylons made from painted 55-gallon oil drums affixed atop 50-foot telephone poles.

Because he didn’t own an airplane, Holm was a gun for hire who, on one occasion, hung out a “Will Race for Food” shingle. Meanwhile, Reno’s gunslinger-in-residence was the swaggering and profane Bill “Tiger” Destefani. Although his leather cowboy hat suggested otherwise, he was actually a Bakersfield, California farmer who discovered his calling when he flew his newly acquired Mustang to Reno in 1980. Destefani is back at the races today, sharing memories. “I thought I’d just give it a try, but then I got hooked, and I’ve been here ever since,” he says while holding court in the Unlimited pits. After funding the development of a Mustang named Strega, Destefani won seven Golds—several collected after epic battles with Lyle Shelton and Rare Bear, which was for many years the fastest piston-engine airplane on the planet.

Bill “Tiger” Destefani, seven-time Unlimited Gold champion.

“I battled that Bearcat for 10 years,” says Destefani. “He won five, and I won five. I don’t know that any one year stood out, because when we won, we were just doing what I expected to do. I always came here to win. Otherwise, I would have stayed home.”

Destefani and Shelton, who died in 2010, each won seven Unlimited Golds. So has Steven Hinton Jr., known as “Steve-o” to distinguish him from his equally celebrated father. A two-time winner in Super Corsair and Red Baron, Steve Hinton—the dad, that is—now flies the jet-powered T-33 that leads the Unlimiteds onto the racecourse. When the airplanes are lined up wingtip to wingtip and ready to hammer “down the chute,” he’ll give the traditional command coined by the late Bob Hoover: “Gentlemen, you have a race.”

“This is my one time at the show, and I’m going to get just enough of a taste of it to really miss it. There will be a big void next September. I don’t know what we’re going to do,” says Stephen Koewler, Argonaut pilot and the 258th and last pilot to be issued an Unlimited license for Reno.

The Hintons, father and son, run Fighter Rebuilders, a restoration shop in Chino, California. Warbird connoisseur Justin Zabel sought them out when he bought the P-51D that raced as Bardahl Special in 1964. Zabel had brought the airplane to Reno in 2022 largely in stock form. But when he heard that 2023 would be the final edition of the air races, Zabel commissioned Fighter Rebuilders to transform the Mustang via full-on racing specs to claim the victory that Love had been denied 60 years ago.

To save time, pieces were pulled off Strega and Voodoo, two highly modded, Gold-winning Mustangs. Composites wizard Andy Chiavetta was hired to fabricate new components. But because the work began so late, it entailed a thrash of epic proportions. “When I told my wife what we were planning to do, she hung up on me for the first time in 24 years,” says crew chief L.D. Hughes, who’s been a fixture at Reno since 1998. “Then she called me back and said, ‘I think you’ve lost your mind.’ ”

Fans like Sherry Souza have kept air racing alive for decades—though its popularity has faded in recent years.

“There were periods when we worked 36 hours straight,” recalls Hughes. “Then we’d sleep for 10 hours and do another 36 hours. It was madness.” But it was all worth it. Going into Sunday’s final, Bardahl Special was the fastest airplane in the field, having posted a qualifying speed of 469.935 mph. Hinton Jr.’s performance had been a master class in Unlimited air racing. He began the lap by rolling nearly 90 degrees with balletic grace to negotiate Pylons 8 and 9, holding the bank rock-steady as he thundered past the pits to start the clock with his clipped wings cutting a perfect furrow through the desert sky and leaving the intoxicating roar of a maxxed-out Rolls-Royce Merlin echoing behind him while he arced around Pylons 1 and 2. Officially, Bardahl Special was running against five other Unlimiteds. But it was clearly in a class of its own.

“We’re going to go home”

As John Melarkey drives his GMC Yukon past a checkpoint on the airfield, a course worker announces, half-joking, half-serious, “Look, it’s the legend himself!”

Before retiring earlier in 2023, Melarkey had spent 56 years as a pylon judge, the last 22 of them as chief. By day, he was a prosperous Reno banker. But the morning after each year’s races ended, he started working on the next year’s pylon program. “What I did was a year-round job,” he says. “When I considered my time, wear and tear on this thing, gas, mileage, all of that kind of stuff, it cost me between $8,000 and $10,000 a year.”

Two P-51Ds, Wee Willie II (at right) and Blondie, make a run toward the grandstands. More than 8,000 P-51Ds were manufactured during World War II; today only around 150 remain airworthy.

Roughly 1,200 volunteers work the event, and RARA needs every one of them. Although the races are said to generate between $100 million and $150 million in revenue for the city of Reno, the actual prize money is underwhelming. A nice Mustang will set you back, say, $3 million, and you’ll have to spend another $1.5 million-plus to make it into a front-line racer. Yet the total purse for all six classes is a tick over $800,000. “The most I ever won here was $200,000,” Destefani says with a snort. “Hell, it cost $150,000 just to refresh the engine.”

Over the years, RARA has done its best to pump up interest in the event. Nowadays, the Reno gathering features civilian airshows. There are also military airpower demonstrations. There are historic airplanes on static display. There are vendors hawking everything from Rolls-Royce Merlin Power T-shirts and thin-frame aviation sunglasses to engine rebuilding services and gazillion-dollar business jets. The grandstands are packed, and, as has been the case for the past two decades, the easternmost portion is a sea of orange. This is the domain of the Section 3 crazies—affable, harmless hooligans who wave madly, blow air horns relentlessly, and brandish orange scoring placards à la Olympic judges.

The biggest change between Reno then and now is the number and variety of airplanes. In 1964, there were a grand total of 19 entries in three classes—Unlimiteds, low-powered Biplanes, and single-seaters (known as Formula 1s). Today, there are more than 125 airplanes in six classes. The T-6 class debuted in 1968. Thirty years later, RARA introduced the Sport class for slick kitplanes such as Lancairs and Glasairs. Jets exceeding 500 mph became eligible in 2002. And four years ago, RARA added the STOL (Short Take-Off and Landing) Drag class for spindly bush-style aircraft. Lamentably, no biplanes were in the 2023 race due to a legal dispute.

Although each class has its devotees, the Unlimiteds are the crowd-pleasing divas of Reno—captivating but temperamental. They’re parked in rows in the middle of the pits, with slender fuselages and nose-up attitudes that make them look like they’re ready to leap into flight. Some sport paint schemes for racing, but many are painted with combat liveries featuring flashy nose art and marks denoting combat victories. “It’s like World War II with the original cast,” says Dwelle.

“It’s going to be tough waving that last checkered flag,” said longtime Reno flagman Dale Tucker on Facebook, as he reflected on the end of an era.

As usual, the Sanders clan is out in force, as it has been every year since 1968, when family patriarch Frank Sanders—who later died in a T-33 crash—made his first pilgrimage to Reno to crew for Greenamyer. Sanders then built a series of Sea Furys raced by his sons, Dennis and Brian. The most famous of them—Dreadnought, hot-rodded with a mighty R-4360 four-row, 28-cylinder radial—has claimed Gold six times. No family has been a more stalwart supporter of the Unlimited community. “We even showed up in 2020 in the middle of covid,” says Dennis’ daughter, Shannon Swager. “We flew over, parked the trailers in our spots, had a beer on the ramp, toasted what would have been, ate dinner, and went home the next day.”

The Sanders family brought three Sea Furys in 2023. Dreadnought was thought to be the only serious rival to Bardahl Special. Unfortunately, Dreadnought ’s engine failed at 440 mph during qualifying, forcing three-time Unlimited champion pilot Joel Swager—Shannon’s husband and Dennis’ business partner—to make an impeccable dead-stick landing. Fortunately, all of the stars aligned to give Sanders’ mechanic (and floatplane pilot) Stephen Koewler the opportunity to fly another family Sea Fury, Argonaut, a few days before the races began. He thus became the 258th and last pilot to be issued an Unlimited license for Reno.

“This is my one time at the show, and I’m going to get just enough of a taste of it to really miss it,” says Koewler. “There will be a big void next September. I don’t know what we’re going to do.”

On Sunday, Koewler feels the tension building as his race—the last of the day—draws nearer. And then, suddenly, silence descends over the airfield. No airplanes flying. No engines being warmed up. And, most ominously of all, no announcements over the P.A.

Rumors ripple through the crowd. Apparently, there’d been a crash after the T-6 race. Some spectators report seeing a puff—smoke? dirt?—northwest of the runway. Then a photographer says he witnessed the aftermath of the accident through his 600-millimeter lens: an airplane missing its tail, arrowing straight into the ground. A mournful shake of his head indicates he can’t imagine any survivors.

The official announcement that two pilots were killed isn’t made until nearly an hour after the accident. Pole-sitter Chris Rushing had outrun Nick Macy by more than 15 seconds in the race. But at an altitude of about 300 feet and not much more than a mile from the runway, their two airplanes collided. Although a preliminary National Transportation Safety Board report didn’t outline a probable cause of the accident, it appears the pilots lost sight of each other while they were in the traffic pattern.

After the crash, pilots were canvassed to see if they wanted to continue racing. There was talk—hopeful or morbid, depending on your perspective—the races would resume after the wreckage was cleared away. But it soon became clear that, no matter what the racers voted to do, the logistical challenges meant the day was over. Reno was done. Air racing might be resurrected in another venue that could create its own legacy. But an era had ended. “Reno’s going out with a whimper instead of a bang,” says pilot (and neurosurgeon) Brent Hisey with a sigh as he stands in the shadow of his venerable P-51D, Miss America.

From 1969 to 2023, Miss America has attended the National Championship Air Races in Reno. The modified warbird, owned by neurosurgeon Brent Hisey, competes in the Unlimited class and is a perennial crowd favorite.

“Miss A,” as it’s fondly called, has been racing in its distinctive red-white-and-blue livery at Reno since 1969, and the soft-spoken Doc Hisey has been chasing Unlimited Gold since he bought the airplane in 1992. “This isn’t an altogether safe sport, but we accept those risks,” he says. “I’m ambivalent about what we should have done. I would have raced if everybody had wanted to race, but if they’d said, ‘No, we’re not going to do this in deference to the family,’ I would have been good with that too. I’m just sad that Reno went out this way, and I’m sad that we went out this way. We would like to have gone out as winners. But, you know, the main thing is we’re going to go home.”

Preston Lerner is a frequent contributor to Air & Space Quarterly.

This article is from the Winter 2024 issue of Air & Space Quarterly, the National Air and Space Museum's signature magazine that explores topics in aviation and space, from the earliest moments of flight to today. Explore the full issue.

Want to receive ad-free hard-copies of Air & Space Quarterly? Join the Museum's National Air and Space Society to subscribe.

Related Topics

You may also like

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.