Have you ever taken a trip to a far away country? Across the Ocean?

If you have, you probably flew on a jet to get there. That wasn't always the case.

You cannot tell the story of international air travel in the United States without talking about Pan Am. Pan American Airways was the nation's sole international airline before World War II. Even after their monopoly on international air travel ended, they continued to define the future of commercial flight—ushering in new technology such as the jet airplane. Pan Am ceased operations in 1991, but by that point the United States had developed a robust international air travel industry.

Founded in 1927, Pan American (also known as Pan Am) opened regular commercial service throughout Latin America using both flying boats and land planes. Pan American was barred from U.S. domestic routes in return for exclusive rights to international routes. In 1935, Juan T. Trippe, founder of Pan American, introduced the first regularly scheduled transpacific service with the famous Martin M-130 China Clipper. He opened regular transatlantic service in 1939 with the Boeing 314 flying boat. Its overseas monopoly lasted until World War II, and its domestic restriction until 1978.

Pan Am's First Transatlantic Flight

In 1939, Pan American Airways made its inaugural transatlantic passenger flight. For William John Eck, it was a voyage for which he had waited eight long years. Finally, he was “Passenger Number One”! He chronicled his journey in a scrapbook, which now resides in the Museum's collection.

For over 40 years, Pan American was the embodiment of its dynamic founder, Juan T. Trippe. During the 1930s, he inspired the famous "Clipper" series of Sikorsky, Martin, and Boeing flying boats. In the 1940s, he bought the pressurized Boeing 307 and Lockheed Constellation and opened the first around-the-world service.

In the 1950s, Trippe introduced the jetliner to America, sponsoring both the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8. In the 1970s, he again set the pace with the wide-body Boeing 747. Pan Am struggled after Trippe retired and the industry was deregulated. It ceased operations in 1991.

From his office in New York City, Pan American president Juan T. Trippe used this globe to plan his airline's expansion around the world. Trippe often would stretch a string between two points on the globe and calculate the distance and time it would take for his airliners to fly between them. Made in the mid-1800s, this globe was featured prominently in many publicity photos of Trippe, and it became part of Pan Am's and Trippe's public image.

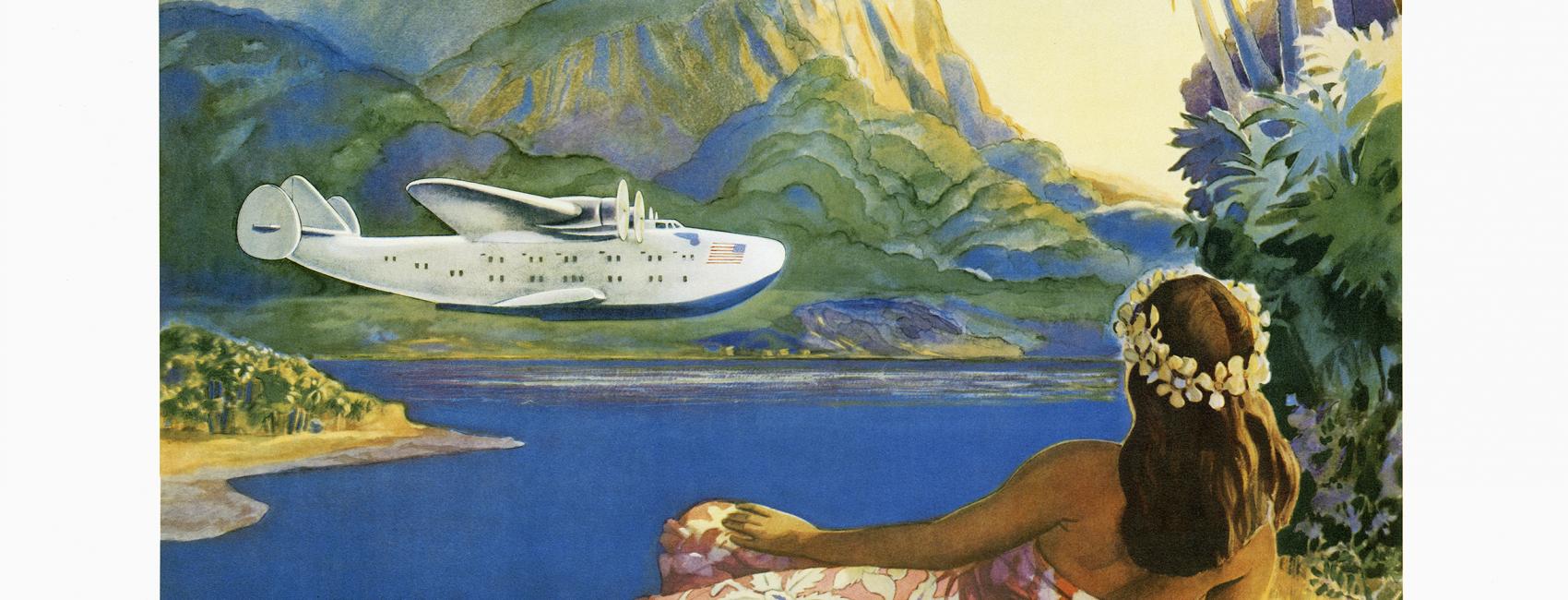

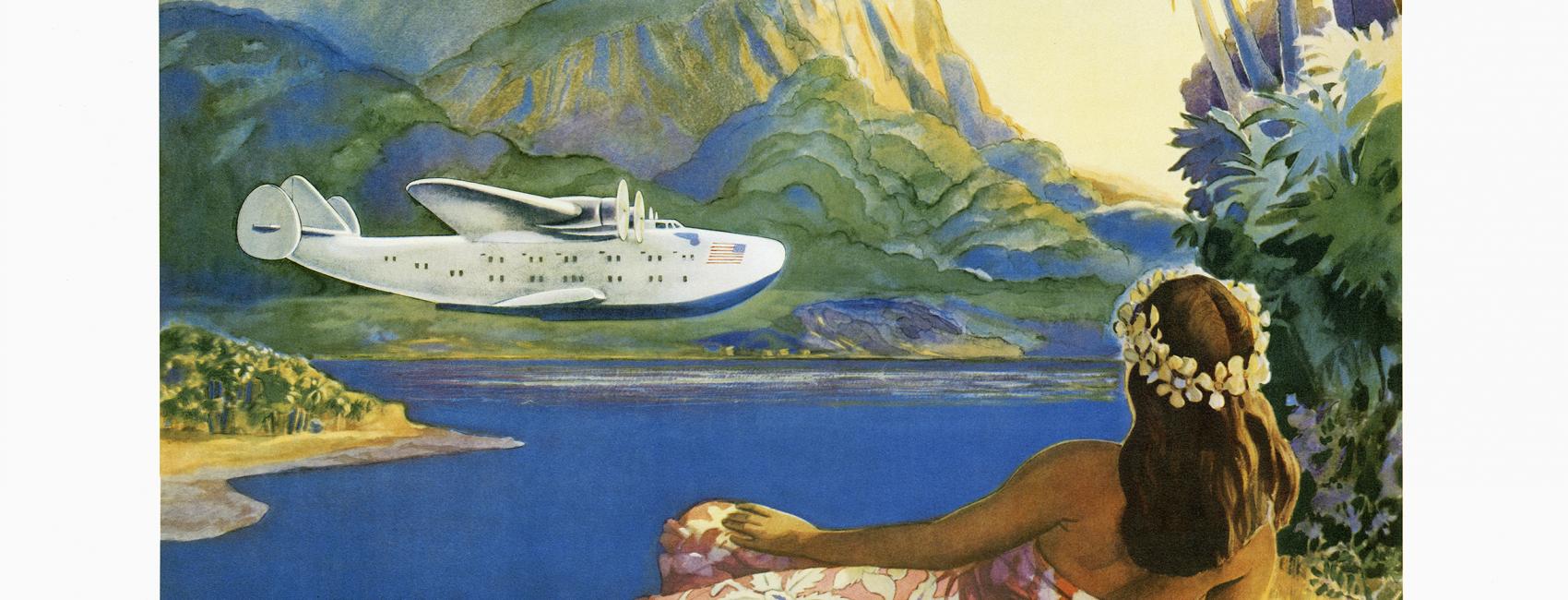

Flying boats became popular in the 1930s because they did not have to contend with the rough state of early airfields. They could also touch down on water in emergencies, thus allaying fears of passengers flying long distances over oceans. And they could be made larger and heavier than other airliners, because they were not restricted by the short length of airfields. Most of Pan American's Latin American destinations were along coasts, so flying boats were a logical choice.

Object Highlight

The Hamilton Standard propeller for this Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp engine seen here was first used on the China Clipper—one of three Martin M-130 flying boats built for Pan American Airways. Opening transpacific passenger service in 1936, the name China Clipper evokes a romantic age of luxurious air travel, when the rich and adventurous flew across the Pacific. The Martin M-130 was the first airliner that could fly the 3,840-kilometer (2,400-mile) distance nonstop between San Francisco and Honolulu, the longest major route in the world without an emergency intermediate landing field. The China Clipper and its sister ships demonstrated that there were no technological barriers to transoceanic travel.

See more aviation posters in the Museum's collection

Pan American Airways was the nation's sole international airline before World War II. During the war, Pan Am helped build a worldwide network of paved runways, enabling the airline to replace its luxurious but inefficient flying boats with four-engine land planes. Pan Am gained much wartime experience delivering high-priority passengers and cargo as well. Thus, it was strongly positioned to dominate postwar international service. However, after the war other domestic airlines were allowed to open international routes. Presidents Roosevelt and Truman both felt it would serve the nation best to have several overseas airlines, and therefore the Civil Aeronautics Board ended Pan Am's monopoly.

Transcontinental and Western Air, with its well-developed domestic network and proven record of overseas war service, quickly became a serious competitor to Pan Am. To reflect the airline's new international status, majority shareholder Howard Hughes changed the airline's name to Trans World Airlines (TWA). Northwest Orient expanded across the Pacific to the Far East. Braniff Airways extended into South America. American Airlines also began international service, but withdrew a few years later.

Even though airlines spent most of their marketing budgets on newspaper and magazine advertisements by the 1950s, posters still played a role in selling air travel. Moreover, with Pan Am losing its monopoly on international flight after World War II, setting themselves apart from new and increasing competition became even more important. Dramatic and colorful airline posters appeared in department and specialty store displays, on city airline ticket counters, and on the walls of travel agents' offices throughout the 1950s. Competing with train and ocean liner advertisements, airline posters in this era usually included at least a small iconic representation of the airplane servicing the route advertised.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, movie stars and other celebrities often flew TWA, which helped fill seats with other passengers. Echoing the glitzy TWA reputation were the airline’s advertising posters, which captured the allure of travel in a single enticing scene, inspiring dreams of adventure in distant locales.

These posters were pervasive — in airports, railway stations, travel agencies, airline ticket offices, hotels, and on advertising kiosks in cities across the globe. Some of the best TWA posters from the 1950s and ‘60s were created by artist David Klein. Klein’s award-winning abstract drawings for TWA came to represent the jet age.

U.S. civil aviation entered the jet age on July 15, 1954, when the Boeing 367-80, or "Dash 80," first took flight. Designed for the U.S. Air Force as a jet tanker-transport, this airplane was the prototype for America's first commercial jet airliner, the Boeing 707.

Boeing 707

Pan American introduced overseas flights on 707s in October 1958. National Airlines soon began domestic jet service using a 707 borrowed from Pan Am. Boeing's 707 was designed for transcontinental or one-stop transatlantic range. But modified with extra fuel tanks and more efficient turbofan engines, 707-300s could fly nonstop across the Atlantic. Boeing built 855 707s.

The Pratt & Whitney JT3 revolutionized air transportation when it entered service on the Boeing 707 in 1958. The new turbojet engine was a commercial version of the U.S. Air Force's J53, introduced in 1950. In the early 1960s, the JT3 was modified into a low-bypass turbofan-the JT3D. The first three compressor stages were replaced with two fan stages, which extended beyond the compressor casing to act like propellers. The resulting increase in airflow lowered fuel consumption, noise, and emissions. JT3Ds became widely used, especially on long-range Boeing 707-300s and Douglas DC-8s.

Boeing 747

Pan American and Boeing again opened a new era in commercial aviation when the first Boeing 747 entered service in January 1970. Designed originally for Pan American to replace the 707, the 747 offered far lower seat-mile costs. It carried 400 passengers (and later versions even more)—more than twice the passengers than the 707 carried. Other wide-body designs soon followed, such as the three-engine McDonnell Douglas DC-10, Lockheed L-1011 TriStar, and the twin-engine Airbus A300.

With its high-bypass turbofan engines and immense seating capacity, the Boeing 747 revolutionized air travel by making flying more affordable. The 747 quickly became the airliner of choice for long-range service.

When the federal government deregulated the airlines in 1978, it gave the airlines the freedom to compete, but they were now also free to fail, and many did. Pan Am's level of service faltered in the 1970s, and the airline began to lose passengers. To gain a domestic network, it bought National Airlines in 1980, but the merger proved costly. The airline began selling its assets, including its lucrative Pacific routes and the famous Pan Am Building in New York. The bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, in 1988 dealt a further blow. America's leading international carrier since 1928, Pan American ceased flying in December 1991.

The future of commercial aviation appeared to be the supersonic transport (SST), an airliner that could fly faster than sound. But concerns about huge development and operational costs, high fuel consumption, drastically high fares, and sonic booms and other environmental issues proved insurmountable. Introduced in 1976, the Concorde was the first and only operational supersonic transport. It could carry 100 passengers across the Atlantic in less than four hours, but its airfares were extremely expensive. All 14 Concordes that went into service were purchased by the British and French governments for their national airlines. Concordes stopped flying in 2003.

Fifty years after the Concorde first flew, a new era of innovation and entrepreneurial ideas seeks to make supersonic flight practical and sustainable. Flying passengers at twice the speed of sound, the Concorde captured the imagination of millions, but was retired in 2003 — so what's next for supersonic flight? From reducing the sonic boom to a quiet thump to the possible pathways for supersonic to return to commercial aviation, join us for a discussion on the supersonic airliner that started it all and where we’re headed next.