Mercury Joins Earth As Tectonically Active Planet

Media Inquiries

Public Inquiries

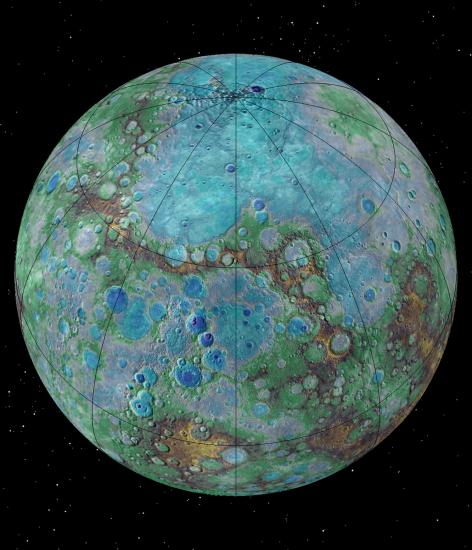

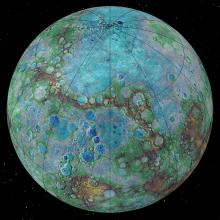

Images obtained by NASA’s MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft during the low-altitude orbital phase of the mission have revealed previously undetected small fault scarps. The young scarps indicate that Mercury is likely still contracting today, which means that Earth is not the only tectonically active planet as previously thought. The findings are reported in a paper led by Smithsonian senior scientist Thomas R. Watters, scheduled for publication in the October issue of Nature Geoscience.

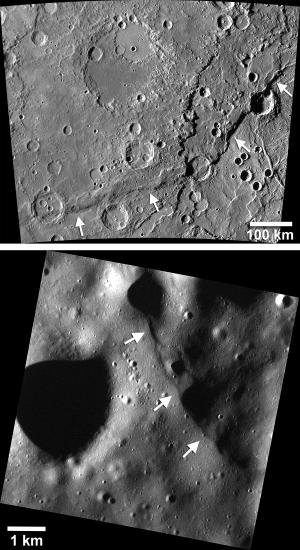

The paper, “Recent tectonic activity on Mercury revealed by small thrust fault scarps,” explains that these newly found scarps are so small that they must be very young. Although they are small, they have big implications for the geologic evolution of Mercury.

“The young age of the small scarps means that Mercury joins Earth as a tectonically active planet in our solar system, with new faults likely forming today as Mercury’s interior continues to cool and the planet contracts,” said Watters of the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the National Air and Space Museum.

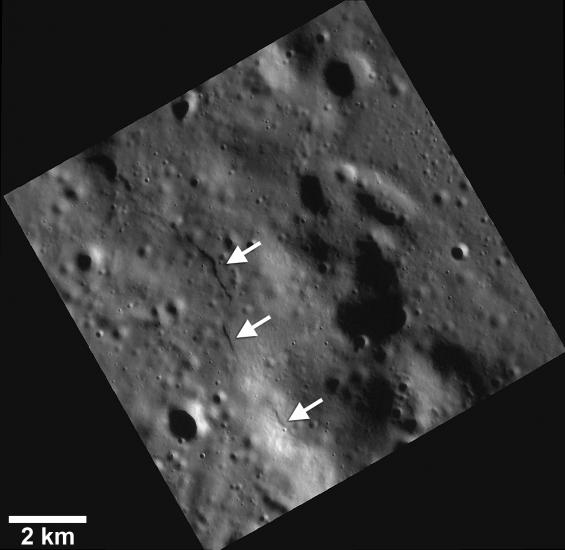

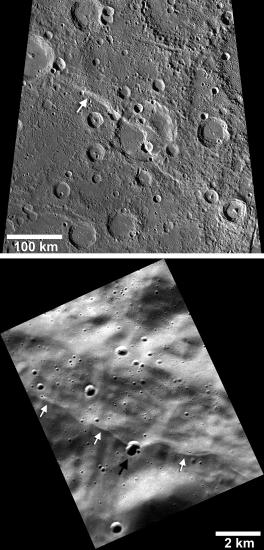

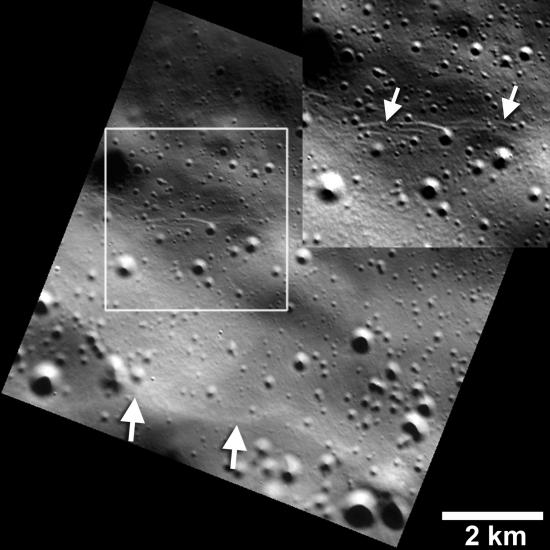

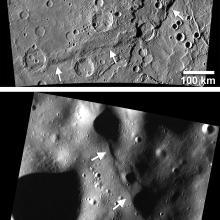

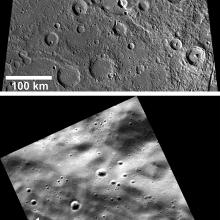

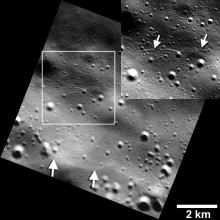

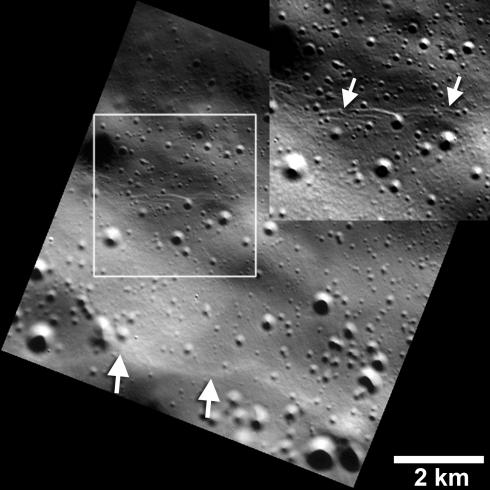

Large fault scarps, cliff-like landforms that look like a giant stair-step in the landscape first found in the flybys of Mariner 10 in the mid-1970s, were confirmed by MESSENGER to indicate the global contraction of Mercury. The large scarps were formed as Mercury’s interior cooled causing the planet to shrink and crustal materials to be pushed together, break and thrust upward along faults making cliffs up to hundreds of kilometers long and more than a kilometer high. In the final 18 months of the MESSENGER mission, the spacecraft’s altitude was lowered allowing the surface of Mercury to be imaged at a much higher resolution. These low-altitude images revealed small fault scarps that are orders of magnitude smaller than the larger scarps. The small scarps, only tens of meters in height and only a few kilometers in length, must be very young to survive the steady meteoroid bombardment, and they are comparable in scale to small, young lunar scarps that are evidence the moon is shrinking.

“The discovery of the small, very young fault scarps on Mercury is like finding a sapling of a tree thought to be long extinct,” Watters said. “The small scarps are the tectonic saplings that with enough contraction can grow in size to become the giant redwoods of Mercury’s fault scarps.”

Currently active faulting goes hand in hand with the recent discovery that Mercury’s global magnetic field has existed for billions of years—both are consistent with long-lived slow cooling of Mercury’s still-hot outer core. Another implication of ongoing tectonic activity is that Mercury is expected to be experiencing current seismicity. Slip-on faults connected to small lunar scarps are possibly associated with recorded shallow moonquakes that reached magnitudes of near five on the Richter scale. Mercury-quakes associated with slip events on newly formed small faults and reactivated older large faults should be detected by seismometers deployed on Mercury on future missions.

MESSENGER was a NASA spacecraft launched Aug. 3, 2004, and it began orbiting Mercury March 18, 2011, and was managed by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. Although it completed its primary science objectives by March 2012, the spacecraft’s mission was extended two times. The mission ended with a planned impact on the surface of Mercury April 30, 2015.

The National Air and Space Museum building on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., is located at Sixth Street and Independence Avenue S.W. The museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center is located in Chantilly, Va., near Washington Dulles International Airport. Attendance at both buildings combined was 8.5 million in 2015, making it the most visited museum in America. The museum’s research, collections, exhibitions and programs focus on aeronautical history, space history and planetary studies. Both buildings are open from 10 a.m. until 5:30 p.m. every day (closed Dec. 25).

# # #