Media Inquiries

Public Inquiries

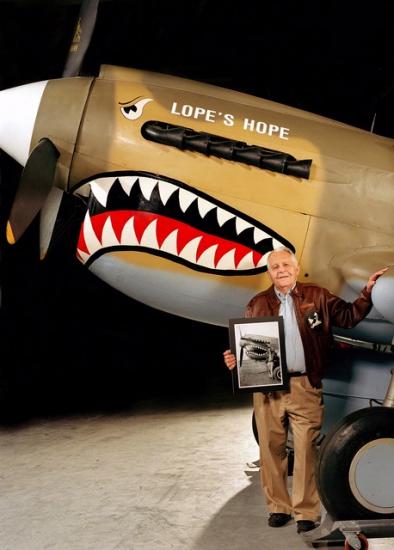

Don Lopez: World War II Flying Ace, Test Pilot, Aeronautics Professor,

Space Program Engineer, Museum Deputy Director

One of the goals of the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum is to acquire, document, and maintain a collection of historically significant aviation artifacts. In the classic sense, "aviation artifacts" refers to inanimate objects such as airplanes and other flight-related objects.

However, the Air and Space Museum is fortunate to also have several aviation icons in human form. The oldest and perhaps most beloved among them, Deputy Director Don Lopez, celebrates his 80th birthday on July 15.

"Don Lopez is a very humble, modest person who has done incredible things," said Jay Spenser, former museum assistant curator and now writer at Boeing. "He is the best representative of the most amazing generation of Americans - those in World War II. He was just a kid, yet he went off and did these brave things."

Lopez was a fighter pilot in the 75th Fighter Squadron, the Flying Sharks, of the 23rd Fighter Group in China. He flew Curtiss P-40s and North American P-51s under Colonel Tex Hill and General Claire Chennault.

Lopez was only 18 years old when the war broke out, and 19 when he shipped off to China in 1943, but he looked much younger. In his book about his experiences he refers to his youthful appearance by saying, "I needed to shave only every other month or so."

Squadron leader Tex Hill thought he had lied about his age. "He looked like he was about 16 years old when he arrived. But he became one of the great fighter pilots of World War II."

Lopez recalled his first mission in his memoirs: "I don't remember feeling any apprehension, only exhilaration...I...was eager to get into combat and never gave any thought to being shot down. I was totally at home in the airplane and completely confident of my ability." He attributes this confidence to having flown so many practice missions in training.

During his two years in China, Lopez flew 101 missions and tallied up five victories, the required number to be called an "ace."

General John "Jack" Dailey, director of the National Air and Space Museum, observed, "Don flew in the most demanding arena and excelled. Being an ace is the validator that a pilot has the courage and the skills to be the best. It is the most prestigious recognition for a pilot."

Lopez wanted to be a fighter pilot since he was a young boy growing up in Brooklyn, N.Y. When he was three, he went with his family to see Charles Lindbergh on parade through the streets of Brooklyn. He was an avid reader of pulp novels about World War I aviation like Flying Aces and Battle Birds.

"An uncle gave me a book about the movie, Wings, and when the movie was showing at a theater a block from our house I got to see it," Lopez said. "It really hooked me on fighter planes."

A family friend who flew barnstorming flights off the beach on the Jamaica Bay shore gave him his first airplane ride when he was about seven. It was in an open-cockpit Waco.

"When I was a little older, I used to ride my bicycle to Floyd Bennett Field. I would stand by the fence looking as sad as I could and occasionally the same family friend would take me up," Lopez said.

When Lopez was a teenager, the family was living in Tampa, Fla., where he spent many hours watching P-39s fly in and out of Drew Air Force Base. In college at the University of Tampa, Lopez signed up for the civilian pilot training program, which was training pilots in case of war. Once war was declared in 1942, the age to be a fighter pilot had dropped to 18, and Lopez immediately joined.

Lopez got his wings on May 28, 1943 and was selected to fly P-40s.

"Back then, everyone was pretty eager to fight," Lopez said. "I think everybody wanted to be a fighter pilot, and when you were selected, you were just overjoyed."

Most of the battles fought in China were against the Nakajima Ki-43 Hyabusa, which means peregrine falcon.

"But we called them Oscars," Lopez said. "They were extremely maneuverable, but we had about the same top speed and we could out dive them because we were heavier and more ruggedly built."

Lopez left China in March of 1945 and spent almost six years testing fighters at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. During the same period, he attended the Air Force Test Pilot School.

Lopez acknowledges what an exciting era it was for a test pilot, "I got to fly everything there was. I flew not only the fighters but the bombers and transports. It was the beginning of the jet age - fighter pilot heaven."

While in Florida, Lopez met his future wife, Glindell, whom he describes in Into the Teeth of the Tiger as "a lovely southern blonde."

"The only thing I would change in my life is that I would meet my wife sooner," Lopez said. They now have two grown children, a son who is one of the world's leading experts on Tibetan Buddhism, and a daughter who is an executive assistant to the head of a clinical economics and genetic research center. They also have one granddaughter.

After his test pilot days, Lopez completed a short combat tour flying North American F-86s in Korea. Following a tour in the Pentagon, he earned a bachelor's degree in aeronautical engineering at the Air Force Institute of Technology and a master's degree in aeronautics from the California Institute of Technology, where future astronaut Frank Borman was a classmate.

"He never lost his calm sense of humor - even at Cal Tech," Borman said. "The academic load was difficult for everyone -- most of us were climbing the walls but he was always completely calm. He is technically very brilliant."

He spent the next five years helping establish the aeronautics program at the new U.S. Air Force Academy as an associate professor of aeronautics and chief of academic counseling. After his retirement from the U.S. Air Force in 1964, Lopez worked as a Systems Engineer on the Apollo-Saturn Launch Vehicle and the Skylab Orbital Workshop for Bellcomm, Inc.

Lopez was brought into the Smithsonian as assistant director of the Aeronautics Division in 1972. He became part of the team led by astronaut and then director of the museum Michael Collins that was responsible for planning the construction and opening of the National Air and Space Museum. As assistant director for Aeronautics, Lopez was instrumental in developing the exhibits that welcomed visitors at the museum's opening on July 1, 1976, which helped it become the most visited museum in the world.

"Don is the creator of this museum from the aeronautics standpoint," Dailey said. "Because of his vast knowledge, he was able to select the right artifacts to tell the story of aviation."

Lopez became deputy director in 1983, a position he held until 1990. He served as senior advisor to the director before retiring in 1993. From 1993 to 1996 Lopez served as senior advisor emeritus. He was again appointed deputy director in 1996.

"Mr. Lopez has been the backbone of the museum, a walking encyclopedia," Spenser said. "His knowledge of aviation is phenomenal. He is a quiet and supportive player behind the scenes."

But his knowledge is not limited to just aviation. He is a voracious reader on just about any topic and is always recommending books to friends and colleagues. As Dailey observes, "He has a huge library and has studied every book - not just read them, but studied them."

When pressed, Lopez ventures to say one of his greatest achievements at the National Air and Space Museum is the Pioneers of Flight Gallery. "Originally, it was supposed to be a temporary exhibit, but I filled it with such great airplanes it hasn't been changed all this time," he said.

Lopez has written two books about his experiences: Into the Teeth of the Tiger (Bantam, 1986), and Fighter Pilot's Heaven: Flight Testing the Early Jets (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995). He also wrote The National Air and Space Museum: A Visit in Pictures (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989).

In May, a P-40 similar to the one he flew in China was delivered for permanent display at the National Air and Space Museum's new companion facility, the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Northern Virginia. Before it was hoisted to the ceiling trusses, Lopez sat in the cockpit and posed in front of the airplane in the exact same position as a photo taken of him in China.

"It was wonderful," Lopez said about that day. "I am proud to have a P-40 here. It felt good to sit in the cockpit - I'd have no trouble flying it today."

"I've been fortunate," he continues. "I've gotten to do lots of good things in my life. I saw the beginning of the jet age, helped establish the aeronautics program at the Air Force Academy, worked for eight years on the space program, and helped found this museum."

People who know Lopez say they are the fortunate ones. As General Dailey points out, "I have never heard anything about him that wasn't complimentary. He is universally loved by everyone."

Interviews with Don Lopez can be arranged by contacting the museum's Office of Public Affairs