Arthur C. Clarke’s Personal Papers Arrive at the Museum

Apr 20, 2015

For much of the latter half of the twentieth century Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008) stood as one of the preeminent authors of science fiction, a noted futurist, and popularizer of science and technology. His collaboration with Stanley Kubrick on the classic film 2001: A Space Odyssey was one signature moment in this broader accomplishment.

For the last several years, we worked with the Arthur C. Clarke Trust to have the author’s papers donated to the Museum. One challenging factor was that the Trust and his papers sat in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Clarke’s home for most of his adult life. Legal and logistical issues abounded. But in Summer 2014, we reached a legal agreement. At the same time, we were fortunate to gain the support of FedEx to help us get Clarke’s collection safely from Sri Lanka to the U.S. In December, my colleague Patti Williams and I traveled to Colombo, welcomed by longtime Clarke associates Rohan de Silva and Hector Ekanayake. We assessed and boxed the collection, and with much help from FedEx’s world-wide team and transportation network, transferred Clarke’s life’s work to its new home in the Museum archives. It is now being conserved and processed, perhaps ready for use by researchers later this fall.

In a future blog, Patti will share more about our effort in Sri Lanka. Here I want to point to why Clarke’s work merits attention. This goes beyond his famed role in 2001 and his standing as the “father” of satellite communications—a moniker earned for his prescient idea, well before the first satellites, of using such machines in geostationary orbit to facilitate communications over transcontinental distances.

What emerges from a first review of his papers is a deeply thoughtful man shaped by and creatively responding to his time—with World War II and the first decades of the Cold War as critically formative. From his early 20s through the rest of life he possessed a remarkably consistent vision and purpose of what was important to him: to make sense of a world experiencing tremendous advances in science and technology, the result of which, in his view, augured potentially radical changes in the fabric of social and cultural life. In the years after the war, this dynamic seemed especially insistent, making the idea and reality of the “future” a critical problem in need of understanding. Through his career, this challenge led Clarke to advance his three laws of prediction (easily found via an internet search), an attempt to make serious the future as a shared, collective human concern but do so with a light touch.

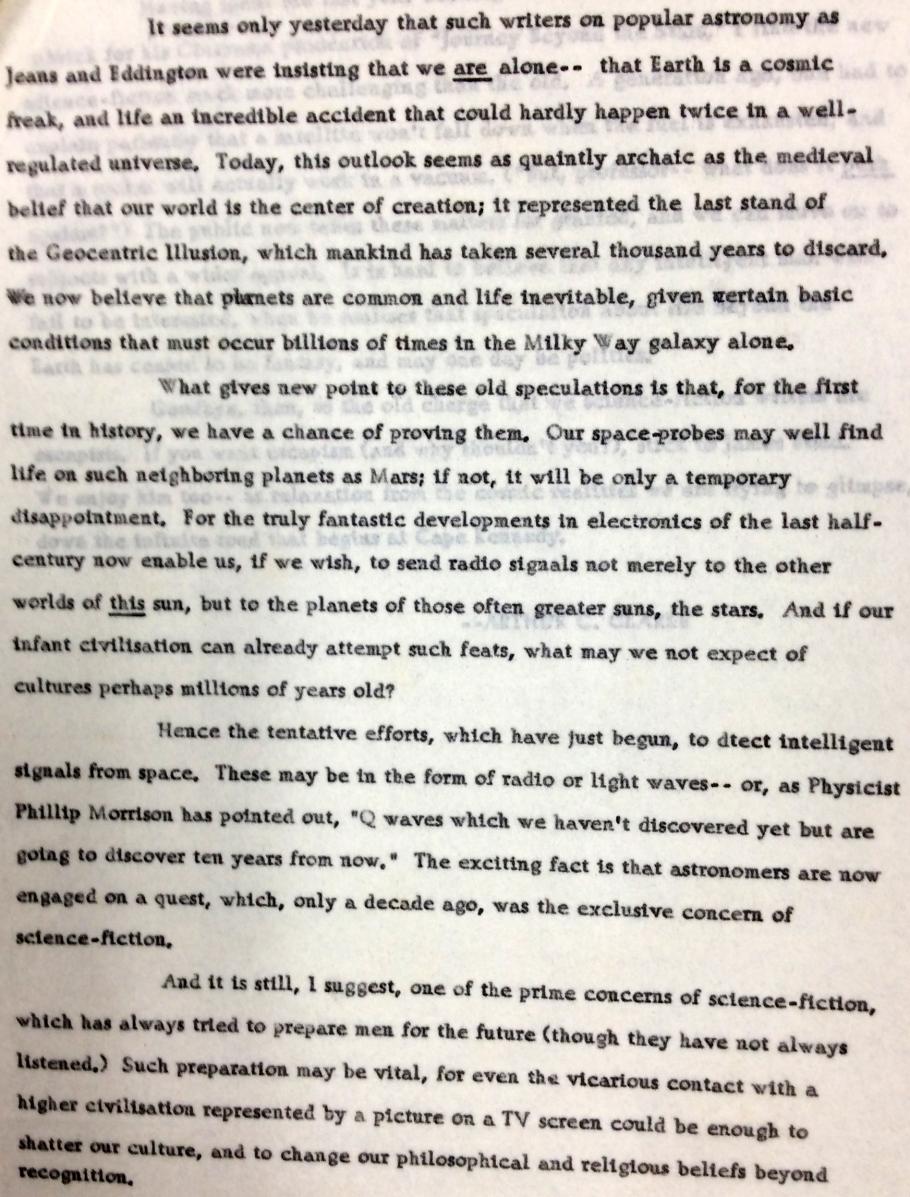

From this vantage, Clarke’s interest in science fiction, as is evident throughout his papers, was not merely incidental but central: It was his essential tool, perhaps the best one, for sorting through and understanding this condition and educating readers about the time in which they were living. This insight helps makes sense, too, of his mix of professional activities: his many books and articles popularizing science and technology, especially on the themes of space technology and exploration, and his many speculations on the future. These efforts and his science fiction writing were all parts of the same project. In his later years, Clarke often said, if he was to have a legacy, he wanted it to be as a writer—asking to be seen whole, not fragmented across his different types of work.

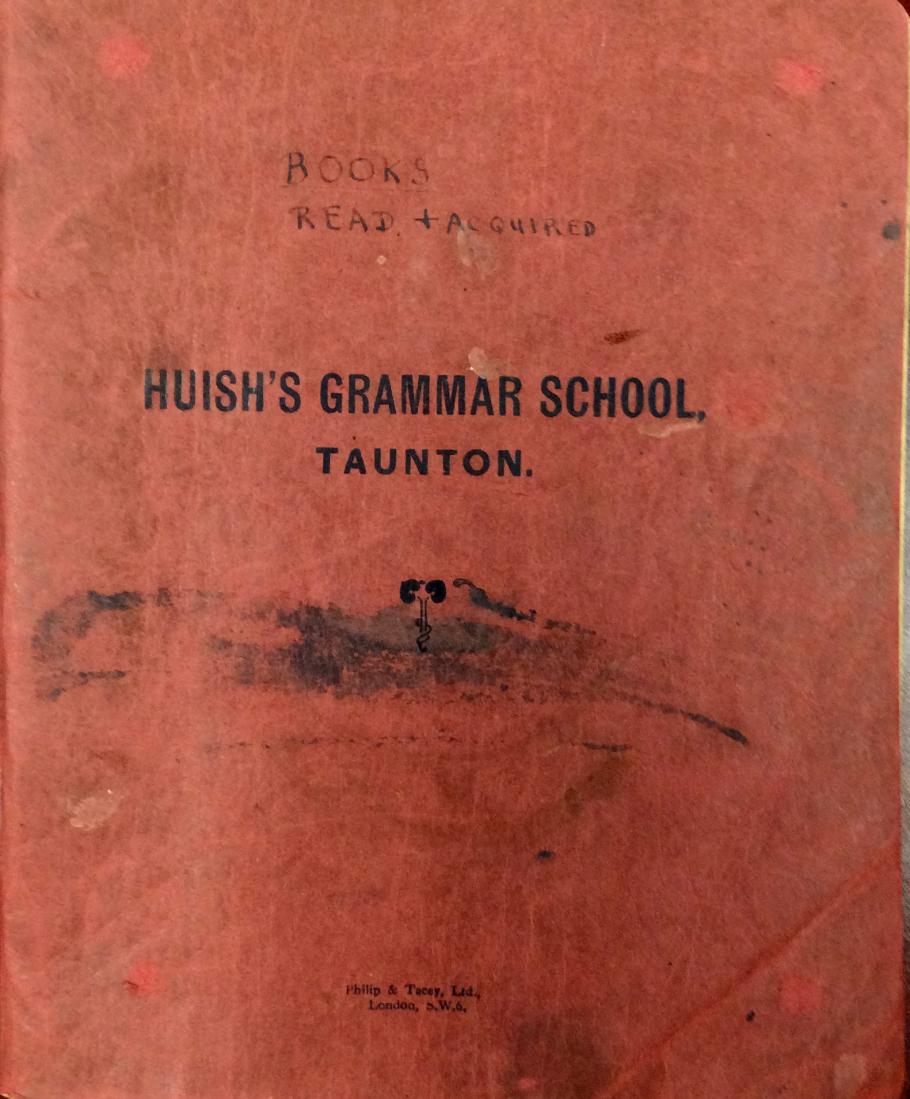

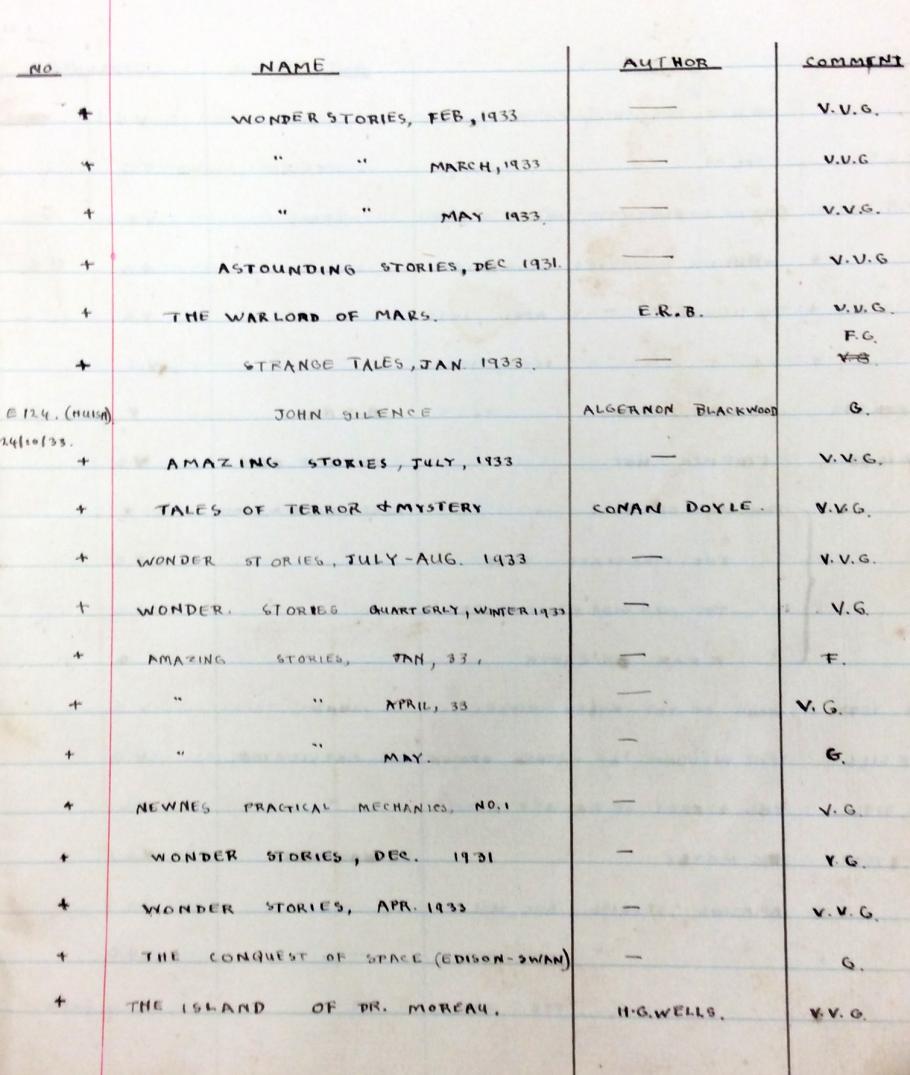

While in school in the 1930s, Clarke already had developed a keen interest in science and speculative fiction. This notebook from his school days in Taunton, Somerset, recorded his program of reading (detail below), in which he not only lists authors/titles, but his assessment of individual works (“G” for good, “VG” for very good, etc.). The notebook also is an indicator of Clarke’s systematic approach as he researched his interests—a characteristic continued through his professional life.

But refashioning the genre of science fiction was, in Clarke’s own estimation, perhaps his most challenging undertaking: he aimed to move this literary form long associated with narratives of escapism or fantasy to one that hewed closely to scientific and technical knowledge—to create a genuine opening for future-oriented reflection and discussion. In 1964, when Clarke and Kubrick began their collaboration on 2001, Clarke in correspondence emphasized their shared desire to create for the first time in cinema history a “really good science-fiction movie”—one organized around Clarkean perspectives.

But there was a deeper layer to Clarke’s thinking. One might simplify his life’s work as seeking an answer to the question of “Where is humanity headed?”—with the second half of the twentieth century as the context shaping both the question and possible answers. For Clarke, such a question was not merely future-leaning, but likely revolutionary. It embodied his belief that humanity was evolving into something fundamentally different, an evolution in which scientific and technical advance played critical parts. This was the reason for Clarke’s intense interest in space exploration: it especially would be the catalyst for an evolutionary change, much like lung-fish climbing out of the ocean millions of years ago to become land creatures (an analogy Clarke often used). But the “climbing out” now would be of humans into space, encountering new environments of change and adaptation, becoming something other than what they had been.

Clarke’s wide appeal as a twentieth century thinker was that in posing this as an emergent condition of the human he was not wild-eyed but a rationalist, believing that the everyday, powerful conjunction of science, technology, and their place in social life had profound implications. But he never delivered such a message baldly. His style, whether in writing, in public appearances, or on television, was unfailingly witty and wryly humorous. His method of education was to do so entertainingly, no matter the medium. This, too, perhaps was part of the historical moment in which he lived.

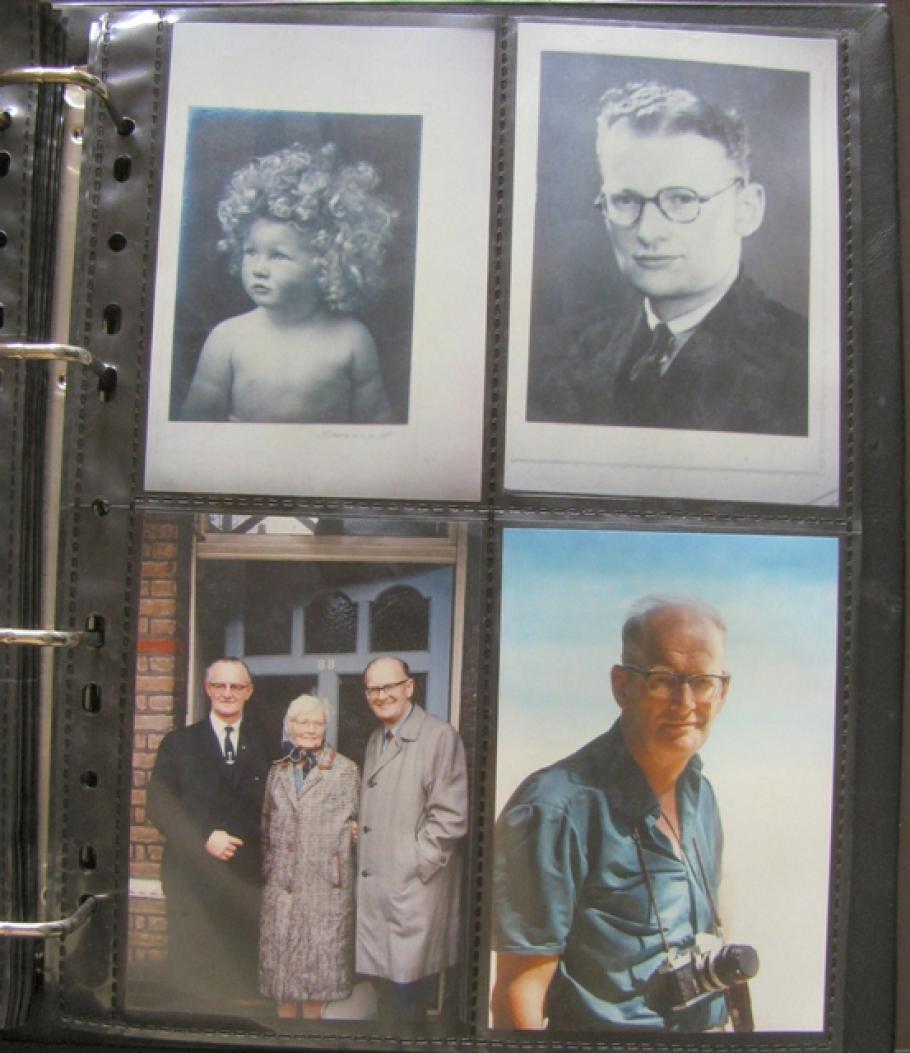

This sketch of Clarke leaves out much. I hope it suggests, though, in broad strokes, why he is an intriguing historical figure, not just for his role in 2001 or other individual accomplishments but as someone who sought to respond creatively to the world in which he lived. That creativity and placement in time are richly documented in his manuscript notes, his correspondence with a wide-range of contemporaries, and an extensive collection of photographs. I am sure in the months ahead we will have more to share on Clarke and his collection.

Related Topics

You may also like

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.