The Beginnings and Basics of Aerial Photography

Jun 21, 2023

Picture the Earth from above. In your mind's eye, what do you see? Today, we have access to air and space technology that lets us see various views of the Earth with ease.

However, before the development of practical aircraft photography, aerial views of the Earth were obtained in different ways. Our first looks at the Earth from above came from kites, rockets, balloons, and even pigeons.

Pigeons

In 1903, Dr. Julius Neubronner patented a miniature pigeon camera activated by a timing mechanism. Equipped with the cameras, the pigeons photographed a castle in Kronberg, Germany around 1908.

In 1903, Dr. Julius Neubronner patented a miniature pigeon camera activated by a timing mechanism. Equipped with the cameras, the pigeons photographed a castle in Kronberg, Germany around 1908.

Pigeons wearing cameras. (Deutsches Museum, Munich)

Balloons

From their early beginnings, balloons soon soared to great heights. They became useful tools in the fields of art, science, and reconnaissance. In 1860, James Wallace Black conducted the first successful aerial photographic effort in the United States when he took a series of photos from Samuel Archer King’s balloon overlooking Boston. Black had previously attempted to photograph Providence, Rhode Island from a balloon but was unsuccessful.

Black’s success came on the eve of the Civil War, where photography from balloons became a key tool in military reconnaissance. Thaddeus Lowe, a pioneer in balloon reconnaissance, flew high above the battlefields to observe troop movements during the Civil War.

Balloon aerial photography continued to be an asset in military reconnaissance long after the Civil War. In 1956, more than 500 plastic reconnaissance balloons were launched for a program called Moby Dick. Under the guise of gathering meteorological information, the balloons were equipped with cameras to photograph Soviet territory.

Kites

In 1895, Lt. Hugh D. Wise of the 9th Infantry Division experimented with photo kites at Madison Barracks, New York. He built a 5.4-meter (18-foot) high kite and attached a box camera to the string. Triggered by a timing device, the camera took photos from an altitude of 180 meters (600 feet).

Rockets

You might think rocketry would enter the picture in the 20th century, but in 1888 Frenchman Amedee Denisse designed a photo rocket. The design is thought to be the first of its kind—however, it wasn’t the last.

Aircraft

From the first clumsy flights and fuzzy photos, airplane photography developed rapidly into a precise and useful tool for looking at Earth. Surveyors, mappers, geologists, resource managers, urban planners, and military strategists have all come to rely on the airplane view of our world. Beyond these practical uses, however, air photographs reveal landscapes of beauty and symmetry that go undetected on the ground level.

The Many Uses of Aerial Photography

Using balloons, and later aircraft, for aerial photography proved to be useful in conducting military reconnaissance—but aerial photography has practical applications in many fields. When the Earth is viewed from the air, patterns, boundaries, and landmarks appear that are often not visible at close range. From this vantage point, the camera can record natural and man-made features and events, from the remains of ancient civilizations to the aftermath of a modern disaster.

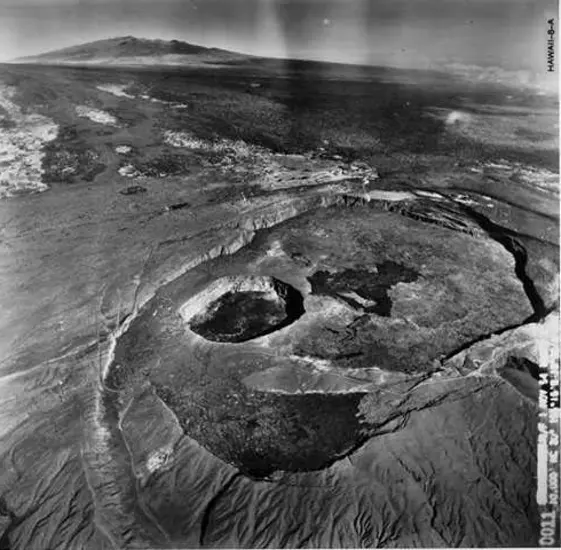

Geology

Archaeology

Disaster Assessment

Monitoring the Environment

When workers became ill during the construction of a public park on Neville Island in Pennsylvania, environmentalists used aerial photos to look back through time and locate the problem.

Different Views

High-altitude photography allows coverage of vast areas on a single frame. Large-scale structures and landmarks can be quickly and conveniently scanned, mapped, or surveyed.

High-resolution photography provides coverage of large areas without loss of fine detail. Both a broad regional overview and a detailed local survey can be combined in one photo.

Airborne radar provides the capability to study geologic structures and terrain characteristics as they extend over large areas. Because radar has the ability to "see" through clouds, imagery is available in all kinds of weather. Radar images have useful applications in the fields of mineral resource exploration and groundwater analysis.

Putting it all Together

Aerial photography is useless without someone to interpret the images produced. Photo interpreters can read an aerial photograph like a book, and they employ many skills to help them analyze the terrain they are viewing.

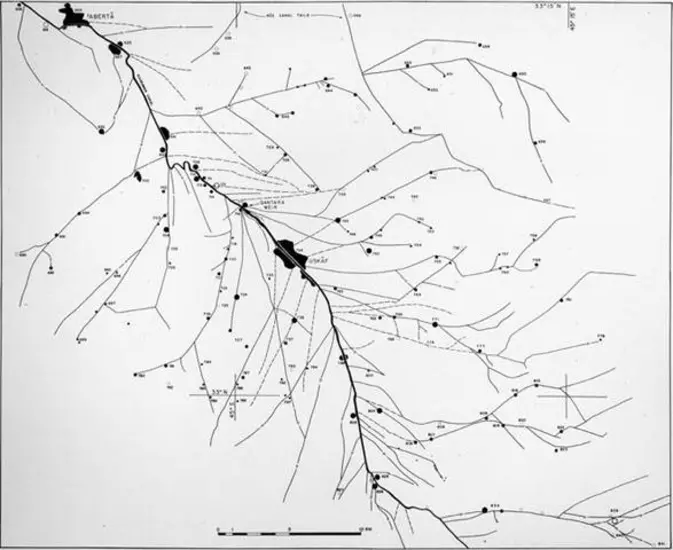

One method that aerial photo interpreters use to view large regions in one glance is called mosaicking. Several photos of adjacent areas are pieced together like a jigsaw puzzle to present the "big picture."

Stereo photography allows the interpreter to see the ground in three dimensions by viewing overlapping photos taken from different locations. To acquire complete stereo photography of an area from above, a series of overlapping photos must be taken along a designated flight line with more than 50% overlap between adjacent photos.

Natural and human-made features can be seen in three dimensions with the aid of a stereoscope (now used mainly for educational purposes) and two overlapping scenes. With the addition of depth, aerial photos can provide the interpreter with more information on geologic boundaries, terrain characteristics, relative heights, and regional topography.

If you have a pair of red/blue glasses, you can simulate the 3D effect of using a stereoscope by viewing these anaglyphs made from aerial photos below.

Aerial photography has a long history and serves as a functional tool for all kinds of work such as military reconnaissance, scientific research, and mapping. The technologies of flight have greatly propelled our ability to see the changing Earth from above.

This story was adapted from the Looking at Earth exhibition.

Related Topics

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.