Bird’s Eye Viewfinder: 160 Years of Aerial Photography

Jul 28, 2018

By Caroline Johnson, Aeronautics Intern

Do you remember the first or last time you stared out the window of an airplane? For me, it was on the descent into John Glenn International Airport in Columbus, Ohio. The grid-like farm scene I watched through my window was seemingly full of life compared to the desert landscape of Texas I had seen on my ascent only two hours prior. Instinctively, I pulled out my cell phone and snapped a picture.

Taking a photograph from the window seat of an airplane has become an involuntary action, but one that is part of a much longer history. Aerial photography made its first appearance 160 years ago, forever changing how we see our environment. In order to change our perspective, however, someone had to be daring enough to combine the monumental innovations of photography and flight.

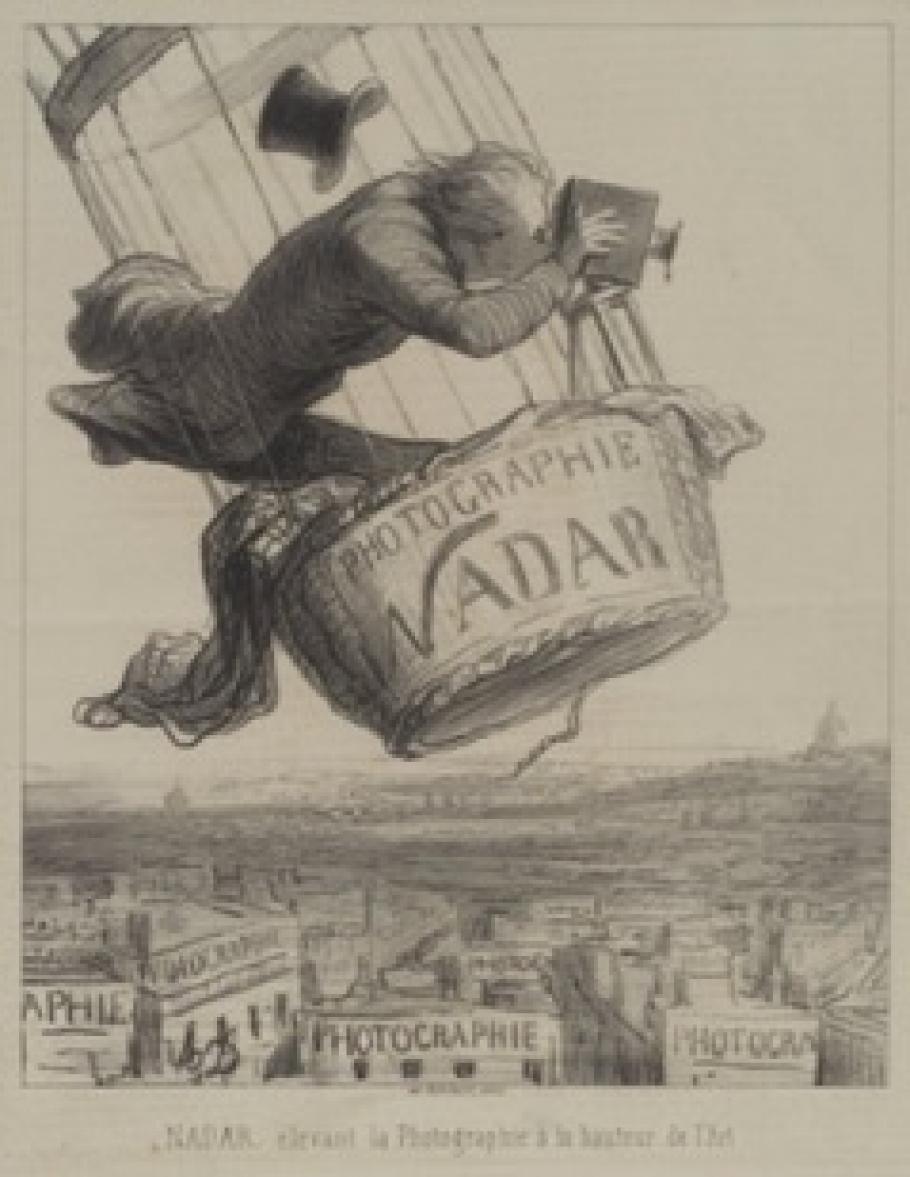

That daring fellow was French photographer Gaspar Félix Tournachon, better known as “Nadar.” In 1858, roughly three decades after the first successful photograph, Nadar captured views of the French village of Petit-Bicêtre (now Petit-Clamart) using a tethered hot air balloon. The mid-19th century collodion process for fixing images was rather complicated, so Nadar carried a complete darkroom in his balloon’s basket. (Talk about exceeding the carry-on restriction!) Though these images no longer exist, Nadar retains credit for the first aerial photographs, marking 1858 as the official “anniversary date” for aerial photography.

Honoré Daumier, "Nadar élevant la Photographie à la hauteur de l'Art" (Nadar elevating Photography to Art), published in Le Boulevard, May 25, 1862.

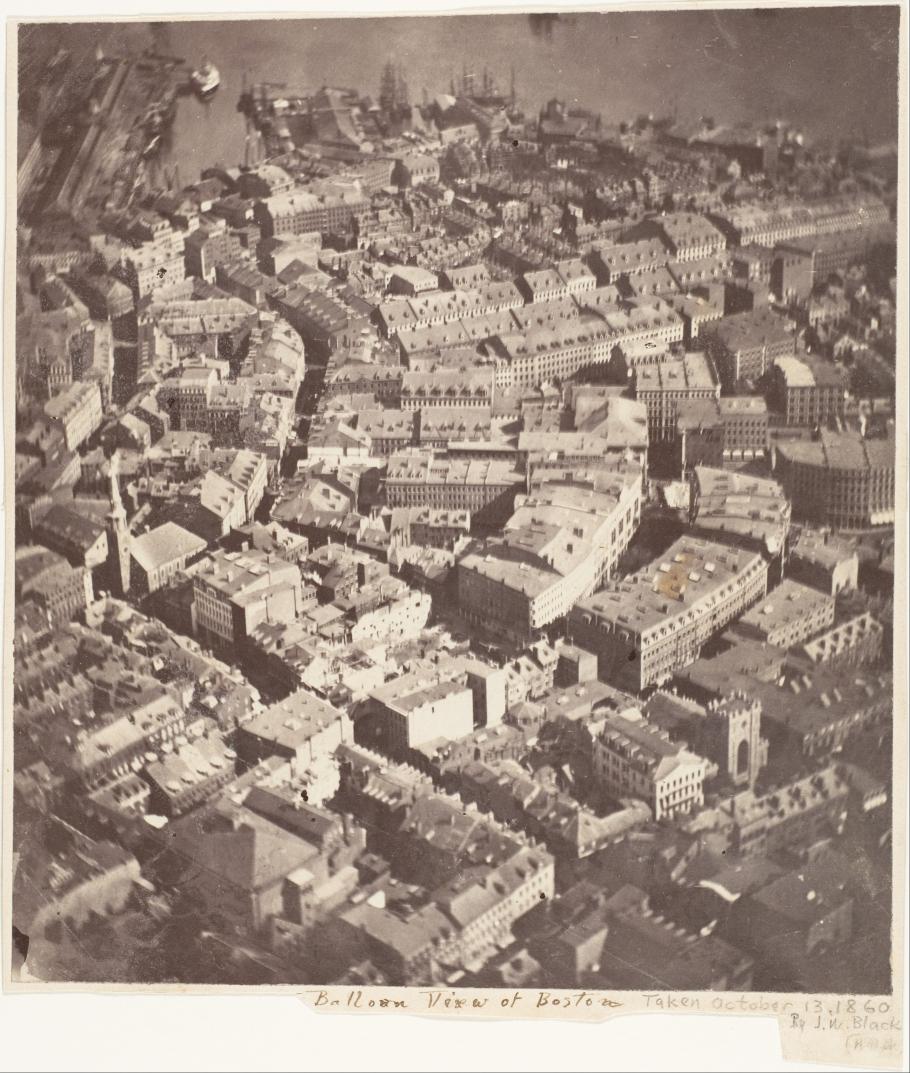

The first aerial image taken in the United States dates only two years later, taken by photographer James Wallace Black. On October 13, 1860, Black and his balloon navigator, Samuel Archer King, made eight exposures from The Queen of the Air, a balloon tethered above Boston, Massachusetts. The wet collodion plates proved a challenge when combined with the movement of the balloon, and only one image was successful. This image, taken at 1200 feet, is the earliest surviving aerial image.

“Boston, as the Eagle and the Wild Goose See It” by James Wallace Black is the earliest surviving aerial photograph. Credit: James Wallace Black, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

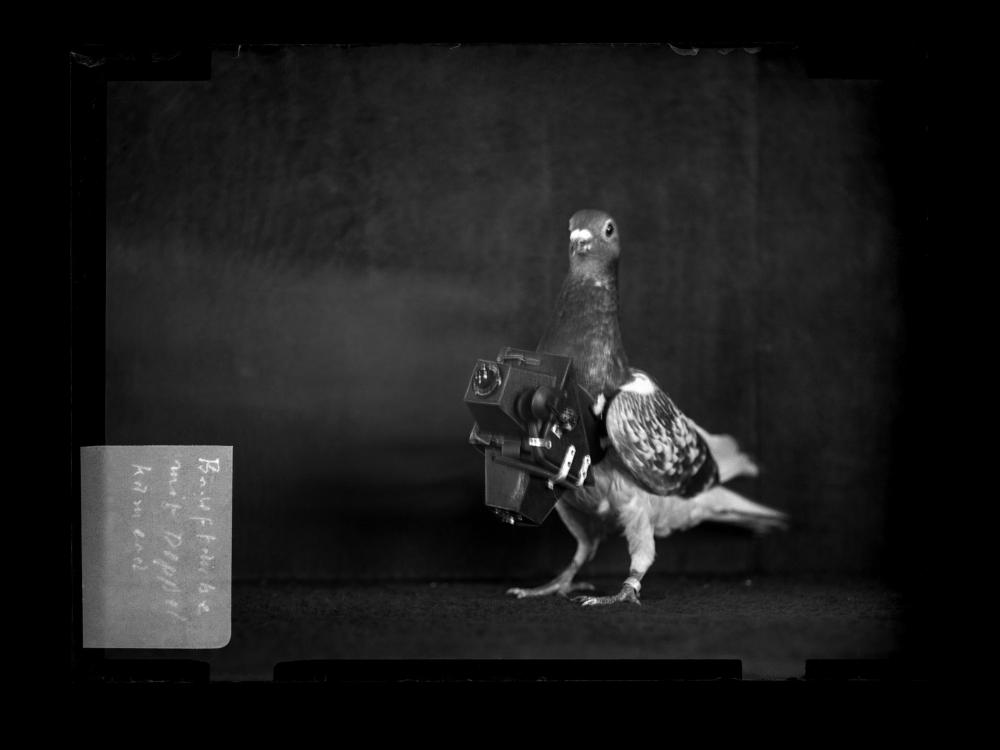

Once airborne, photographers tested cameras on a multitude of gravity-defying objects. Experimentations with kites and rockets utilizing explosive charges proved successful, but some opted for a more “natural” form of flight. In 1907, German apothecary Julius Neubronner attempted to patent his new pigeon camera. Neubronner crafted aluminum harnesses, which allowed him to attach a lightweight time-delayed camera to a pigeon’s breast. Such images captured a true “bird’s eye view” of German streets, but their unreliable quality meant they were soon surpassed by other forms of aerial photography.

Julius Neubronner's “Pigeon Camera.” Credit: Rorhof/Stadtarchiv Kronberg

By 1909, photography was combined with the aircraft, as Wilbur Wright assisted in marketing planes to the Italian government. His passenger, cinematographer L.P. Vonvillain, photographed the military field at Centocelli, foreshadowing photography’s next aerial role in military operations. The development of reconnaissance aircraft to record enemy movements and defenses during World War I further fueled the airborne use of photography. With the vast technological advances during the twentieth century, aerial photography quickly became a tool for a wide range of intelligence efforts.

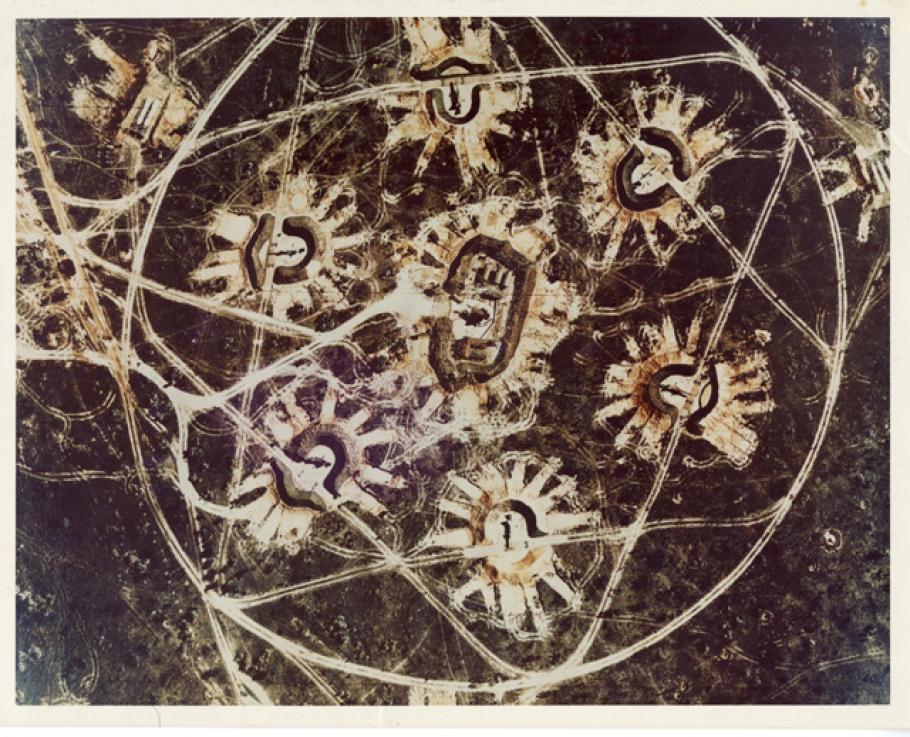

Some of the most well known aerial reconnaissance efforts using photography occurred during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Photo analyst Dino Brugioni, with Eisenhower’s stamp of approval, helped found the CIA’s National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC) in 1961. Brugioni’s collection lives at the National Air and Space Museum Archives and provides a fascinating story of the role of photographic aerial reconnaissance. Among the collection are images of the Light Photographic Squadron 62 (VFP-62), also known as the “Fightin’ Photo” Squadron. The primary mission of VFP-62 was “to provide aerial photographic intelligence for naval operations.”

Though the “Fightin’ Photos” are famous for capturing some of the first low-level photographs of Soviet missile bases in Cuba, several other airframes, including Lockheed U-2s, assisted in identifying Soviet SA-2 missiles at high altitude. The identification of these missile sites proved crucial for President Kennedy’s immediate response to mitigate the threat at hand.

Straight vertical color aerial reconnaissance photograph showing a Soviet SA-2 Missile (V-75 Dvina, Guideline) surface to air missile (SAM) site in La Coloma, Cuba, November 10, 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Taken by a Lockheed U-2, this is one of the first color aerial reconnaissance photographs.

By the 1980s and into the turn of the millennium, advancements in cameras and other technologies increased the accessibility and general use of aerial photography. Spaceborne vehicles and satellite imagery only furthered the ability to view Earth from above, as composite images could be stitched together to view an entire hemisphere. The boundaries between the human and the technological are continuously blurred with the increased reliance on remotely piloted aircraft--drones. Though primarily used in military and intelligence efforts throughout the 1980s and 1990s, civilian and commercial use of drones has skyrocketed in the last decade.

In 160 years, the ability to take aerial photographs has altered the way in which we see ourselves and planet Earth. Next time you take a picture from the sky, take a moment to reflect on how that image fits into a larger narrative of aerial photography. Whether from a hot air balloon, pigeon, or aircraft, the ability to capture aerial imagery highlights the human capacity to move beyond the confines of Earth in both practical and awe-inspiring ways.

Related Topics

You may also like

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.