Jul 21, 2011

Intro

July 21, 2011, marks the ninetieth anniversary of the sinking of the captured German battleship Ostfriesland by the First Provisional Air Brigade of the U.S. Army Air Service. This unit was commanded by Brig. General William “Billy” Mitchell, one of the most controversial figures in the history of air power in the United States. Mitchell was air power’s most prominent American proponent in the 1920s, often to the chagrin of the regular Army leadership. Although commonly perceived as a one-time affair, the sinking of the Ostfriesland was in fact the culmination of a series of bombing tests conducted by the U.S. Navy and the Air Service from May 1921 to July 1921. Mitchell’s advocates and promoters have pointed to the sinking of the Ostrfriesland as being a significant milestone in the history of American air power. Nevertheless, the historical context that surrounds it remains a matter of some controversy to this day.

Service in World War I and Immediate Postwar Years

Mitchell was a decorated veteran airman who had commanded the American air combat units in France during World War I. As such he was responsible for aerial operations in the St. Mihiel salient during the war, and he had been, according to his most prominent biographer, Alfred Hurley (Billy Mitchell, Crusader for Air Power), strongly influenced by the ideas of the British General Hugh “Boom” Trenchard, head of the Royal Flying Corps, and later of the Royal Air Force (RAF) regarding aircraft as offensive weapons. On Mitchell’s return to the United States, he fully expected to be named chief of the Air Service. Instead the post went to Charles T. Menoher, a distinguished WWI infantry commander and protégé of General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces during the war, and now Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army. Mitchell nevertheless was undeterred in his attempt to take his arguments in favor of air power to congressional leaders and the public. His ultimate goal was a completely independent air force much like the RAF within a Department of Aeronautics.

The Sinking of the Ostfriesland

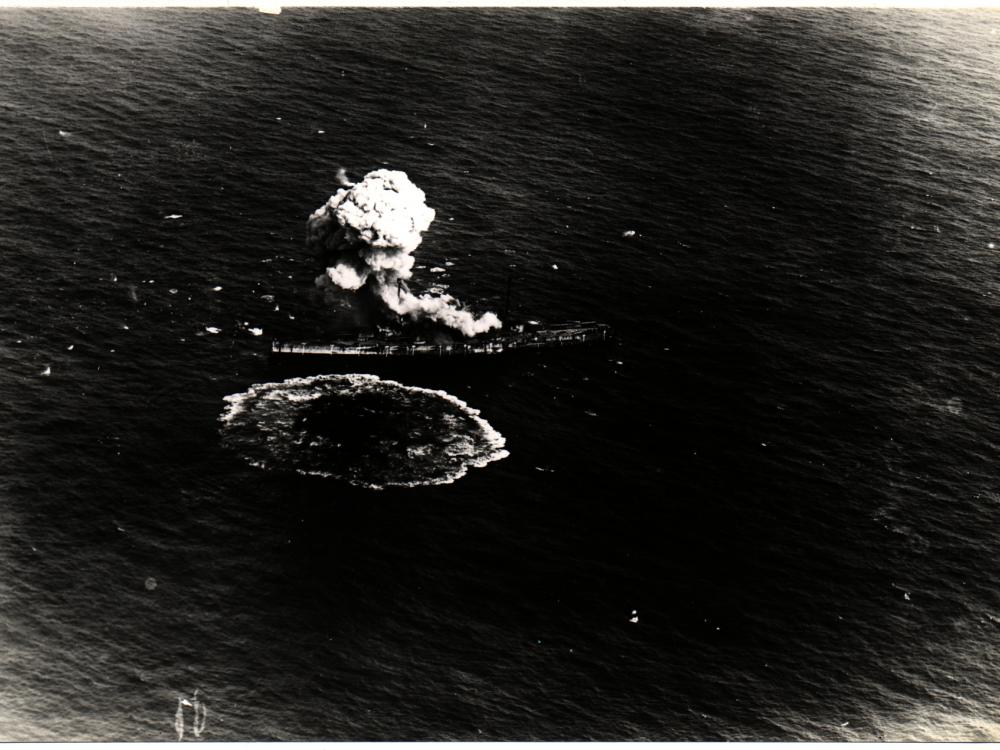

Mitchell used his influence in Congress to allow the U.S. Air Service to participate in naval bombing tests that took place during the summer months of 1921. The U.S. Navy put tight controls on the tests to restrict Mitchell and the Air Service. The targets were captured German navy ships, including a submarine (U-117), the USS Iowa, a battleship converted to a radio-controlled fleet target ship, a destroyer (G-102), a German light cruiser Frankfurt, and finally, the German battleship Ostfriesland. The sinking of the Ostfriesland on July 21, 1921, was the most controversial event of the bombing tests. Ignoring the Navy’s restrictions about pressing the attack too vigorously, Mitchell decided to sink the Ostfriesland in direct fashion. After an attack by aircraft carrying 1,000 lb. bombs, his airmen dropped six 2,000 lb. bombs on the battleship, and in a twenty-minute period, the Ostfriesland was sent to the bottom of the sea. No direct hits were scored, however. The Navy protested vigorously that their construction experts were not given enough time to examine the ship, but to no avail.

Mitchell had seized the day despite the fact that the Ostfriesland was at anchor and unable to maneuver and there was no defensive antiaircraft fire to hinder the aerial attacks. As Alfred Hurley remarks, “the dispute could not get away from the basic fact which deeply impressed itself on the public’s mind, Mitchell had sunk a battleship, as he claimed he could.” (68) The Joint Army Navy Board, which had been created in 1903 by President Theodore Roosevelt to plan combined operations and prevent any difficulties that might arise from interservice rivalries, produced an evaluation of the tests. The Board’s report, signed by General Pershing himself, fell far short of Mitchell’s recommendations for a separate aerial arm, with responsibility for all aviation within and beyond the United States. Mitchell, as expected, cast aside the recommendations of the Joint Board, and produced his own report, leaked to the press, which said that the problem of aircraft being able to destroy seacraft had been solved, and that there were “no conditions in which seacraft can operate efficiently in which aircraft cannot operate efficiently.”

Court Martial in 1925

In late 1924, Mitchell gave provocative testimony before the House Select Committee of Inquiry into Operations for the United States Air Service (the Lampert Committee) during which he said “It is a very serious question whether airpower is auxiliary to the Army and the Navy, or whether armies and navies are not actually auxiliary to airpower.” In March 1925, Mitchell reverted to his permanent rank of colonel, and was transferred to San Antonio, Texas. This demotion and removal from Washington was seen as punitive and disciplinary, but it did not deter Mitchell from his crusade. On September 3, 1925, the U.S. Navy airship Shenandoah (ZR-1) crashed over Ohio. This event came on the heels of another aviation disaster, when the U.S. Navy flying boat PN9 No. 1 was lost at sea in the Pacific Ocean en route from San Francisco to Honolulu. Mitchell was incensed, and he unleashed an attack on the Navy and War Departments for “incompetency, criminal negligence and almost treasonable administration of the National Defense.” He accused the Coolidge administration and military leaders of giving false, incomplete, or misleading information to Congress, and forcing military airmen to provide false information on the state of military aviation. For the Coolidge administration, this was the last straw. In October 1925, the War Department began proceedings to court martial Mitchell, who was convicted but chose to resign his commission.

Assessment

So, how significant were Mitchell’s crusade for air power and the subsequent sinking of the Ostfriesland and its aftermath to the growth of air power and of strategic bombardment theory and practice in particular, and to the creation of an independent air force? Institutional military historians believe Mitchell was important not so much as a theorist, but as a prophet, promoter and martyr. Some, like Alfred Hurley, challenge his methods, admit that he made mistakes, but tend to revere him nonetheless. James J. Cooke (Billy Mitchell) is less sympathetic. Cooke writes that “the warts, and there were many, were ignored. Writers tended to see Mitchell as they wanted to and made out of him the knight of the air, which despite his many accomplishments he was not.” (286) Rondall R. Rice, author of The Politics of Air Power: From Confrontation to Cooperation in Army Aviation Civil-Military Relations, believes Mitchell was clearly insubordinate and deserved to be court-martialed. He is astonished at the adulation Mitchell receives from contemporary Air Force leaders.

What can be said about Mitchell’s influence on the development of American strategic bombing theory? Thomas H. Greer, The Development of Air Doctrine in the Army Air Arm, 1917-1941, rightfully points out that “the principal change in the tenor of the arguments over air power, in the period from 1926 [the year in which the Air Corps Act was passed] to 1935, derived from technological advances in aircraft production. … .” (44) Another factor that Greer points to is “technical developments in bomb-sight construction” particularly the Norden Mark XV bombsight, first demonstrated to the Air Corps in October 1931.(57) Doctrine also played a part, and its influence came chiefly from the Air Corps Tactical School (ACTS), established in 1920 at Langley Field, Va. In 1931, the school was moved to Maxwell Field, Alabama. The idea of limited area bombing was being taught at ACTS in 1926. Within a few years this notion was dropped, and the new precision idea, with its related tactics, began to take form. Certainly one factor that affected the evolution of bombardment thought was the general public opposition to mass civilian bombings. Whatever the reasons, the ACTS focused a great deal of attention on high-altitude, daylight precision bombing doctrine, and target selection—“choke points” as they were known—that would cripple the enemy’s economy and its ability to wage war.

Of course, all of this theory had yet to be put into practice, but by the late 1930s, the Air Corps had two of the key technological elements in their quest to practice strategic bombing: the Boeing B-17 and the Norden bombsight. An independent United States Air Force would not be created until after World War II (1947) when air power, after many fits and starts, had shown that it could be employed effectively under the right conditions in wartime. Mitchell’s ideas about Army and Navy subordination to the air force were never proven. After the Vietnam War, the emphasis, despite continued bitter interservice budget battles, has been on cooperation and coordinated effort.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Bob Cerovich, an informed reader who noticed errors in the photographic captions that we ran originally. We have corrected the text, and will see to it that the captions for photographs we hold that relate to the bombing trials conducted in 1921 and subsequent trials are revised accordingly.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.