Georgia “Tiny” Broadwick’s Parachute

Mar 12, 2015

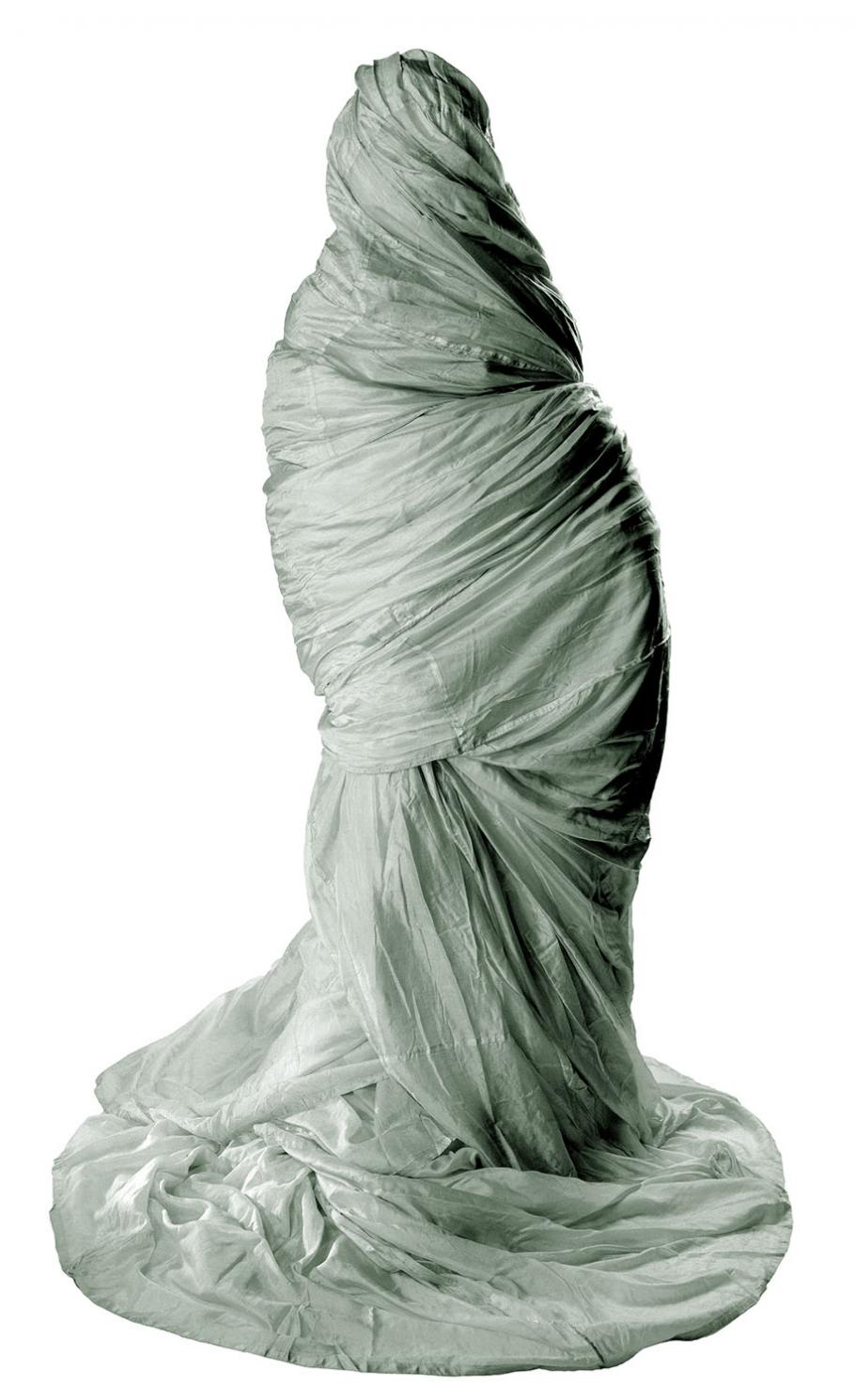

In 1964, a woman named Georgia “Tiny” Broadwick donated this parachute, which was handmade by Charles Broadwick and consists of 110 yards of silk, to the Smithsonian’s National Air Museum, precursor to the National Air and Space Museum. Just who was Tiny Broadwick and what is her connection to parachuting?

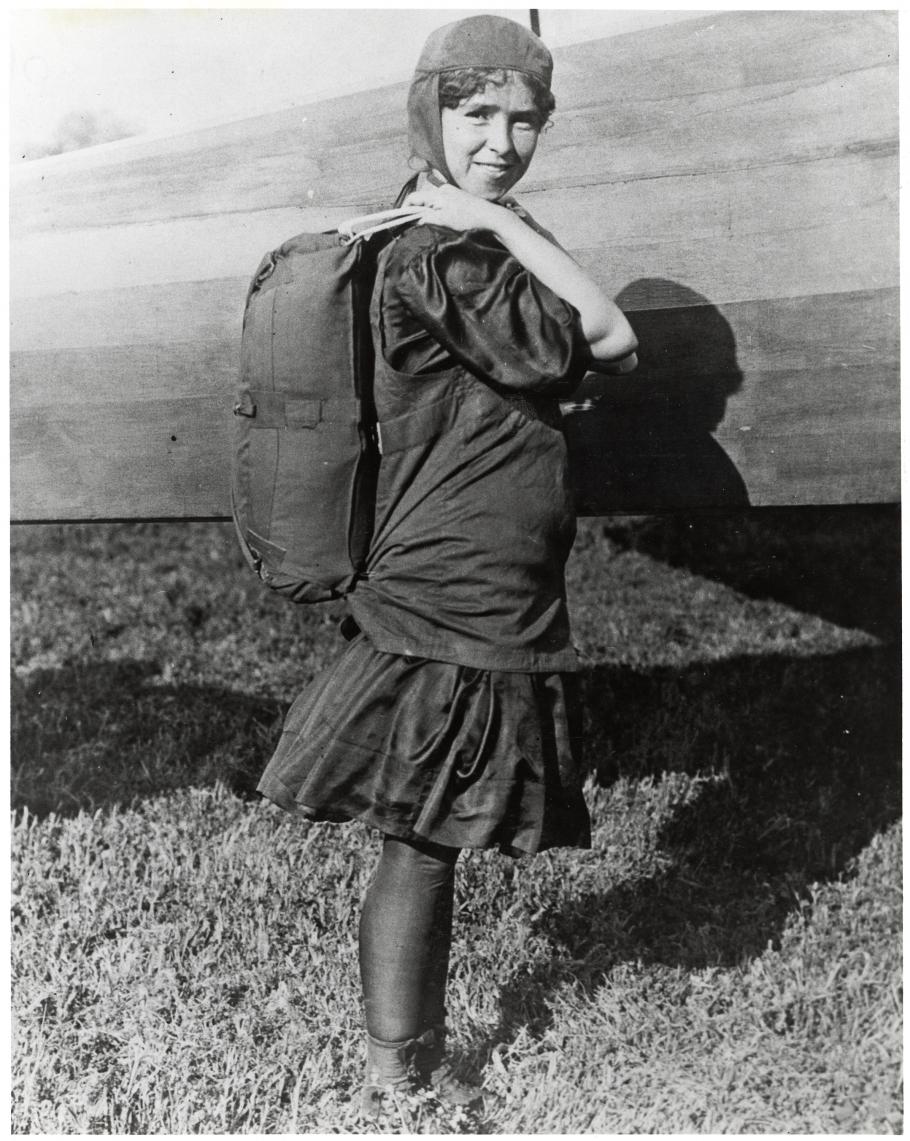

Tiny got her nickname when she was born Georgia Ann Thompson in North Carolina on April 8, 1893 weighing just 1.4 kilos (3 lbs.). Even when fully grown, she was just over 1.5 meters tall (5 feet) and weighed about 36 kilos (80 lbs.), so the nickname stuck. Tiny was just 15 years old when she jumped from a hot-air balloon at the 1908 North Carolina State Fair. Describing her feelings later, she said, “I tell you, honey, it was the most wonderful sensation in the world!” It was a thrill she would come to experience some 1,000 times in her life. Tiny first became interested in jumping in 1907 when she saw an act called, “The Broadwicks and their Famous French Aeronauts,” in which performers would ascend in a balloon and then parachute out. “I knew that’s all I ever wanted to do!” she commented after seeing the show. She approached the owner of the troupe, Charles Broadwick, and convinced him to hire her. Her diminutive size worked to her advantage, since Broadwick saw the potential in billing her as the “Doll Girl,” dressing her in ruffled bloomers, a silk dress, ribbons in her ringlets, and a bonnet. Although she hated the name and the costume, she soon became the star of the show.

Charles Broadwick legally adopted Tiny and her name became Tiny Broadwick. They traveled all over the United States with the popular balloon act, during which the dauntless Tiny performed daring jumps, sometimes with flares or torches. She had several harrowing mishaps during her career. She once landed on top of the caboose of a train, and got tangled in a windmill and high tension wires. She also had many rough landings in which she broke bones and dislocated her shoulder on several occasions, but she never lost her enthusiasm for jumping. One day at a Los Angeles air meet she and Charles Broadwick met famed stunt flyer and airplane manufacturer Glenn L. Martin, who had seen her jump. He proposed that she jump from one of his airplanes, a chance she seized without hesitation, making her the first woman to parachute from an airplane on June 21, 1913. To perform this feat, Tiny hung from a trapeze-like swing suspended beneath Martin’s airplane just behind the wing. Her parachute, which was developed by Charles Broadwick, was on a shelf above her, and when the plane was at 2,000 feet over Los Angeles, Tiny released a lever that made the seat drop out from under her. The parachute, which was attached to the airplane by a string, opened automatically, and she floated safely to earth, landing in Griffith Park.

Later that year, Tiny became the first woman to parachute into a body of water, namely, Lake Michigan. In 1914, her reputation as a parachutist led to the U.S. Army contacting her. World War I was raging in Europe, and many pilots were lost because they had no way to escape from a falling airplane. Tiny was asked to demonstrate jumping from a military airplane, and she made four jumps at San Diego’s North Island. After three successful jumps, her fourth didn’t go so well. Her parachute’s line became tangled in the airplane’s tail assembly and the strong winds prevented her from getting back in the airplane. But Tiny did not panic; instead she had the idea to cut the line to a short length and free fall toward the ground, then pulling the line by hand to open the parachute. This was, in essence, the first planned free-fall descent, and the first demonstration of what would later be called the “rip cord.” She had proven that a pilot could return to the ground safely by bailing out of an airplane.

Tiny’s last jump was in 1922, when she was just 29 years old. Sadly for her, problems with her ankles prevented her from continuing as a parachutist. She stated at the time, “I breathe so much better up there, and it’s so peaceful being that near to God.” Tiny received many honors and awards in her lifetime. Among them are the U.S. Government Pioneer Aviation award and the John Glenn Medal. She is one of the few women in the Early Birds of Aviation. She also received the Gold Wings of the Adventurer’s Club in Los Angeles, and was made an honorary member of the 82nd Airborne Division at Ft. Bragg. With that honor, she was told she could jump any time she chose. At the May 5, 1964 Tiny Broadwick Night dinner during which Tiny donated her parachute, National Air Museum Director Philip S. Hopkins said, “Measured in feet and inches, her nickname ‘Tiny’ is obviously appropriate. Measured by her courage and by her accomplishments, she stands tall among her many colleagues — the pioneers of flight. And her contributions to flight history have helped to make America stand tall as the nation which gave wings to the world.” Tiny Broadwick died in 1978 at age 85 and was buried in her home state of North Carolina. Watch a 1963 interview with Tiny Broadwick from the state archives of North Carolina, conducted by news reporter Ben Runkle of WRAL. For more information on Tiny, read Tiny Broadwick: First Lady of Parachuting by Elizabeth Whitley Roberson.

Related Topics

You may also like

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.