Mar 12, 2025

By Caroline E. Tapp

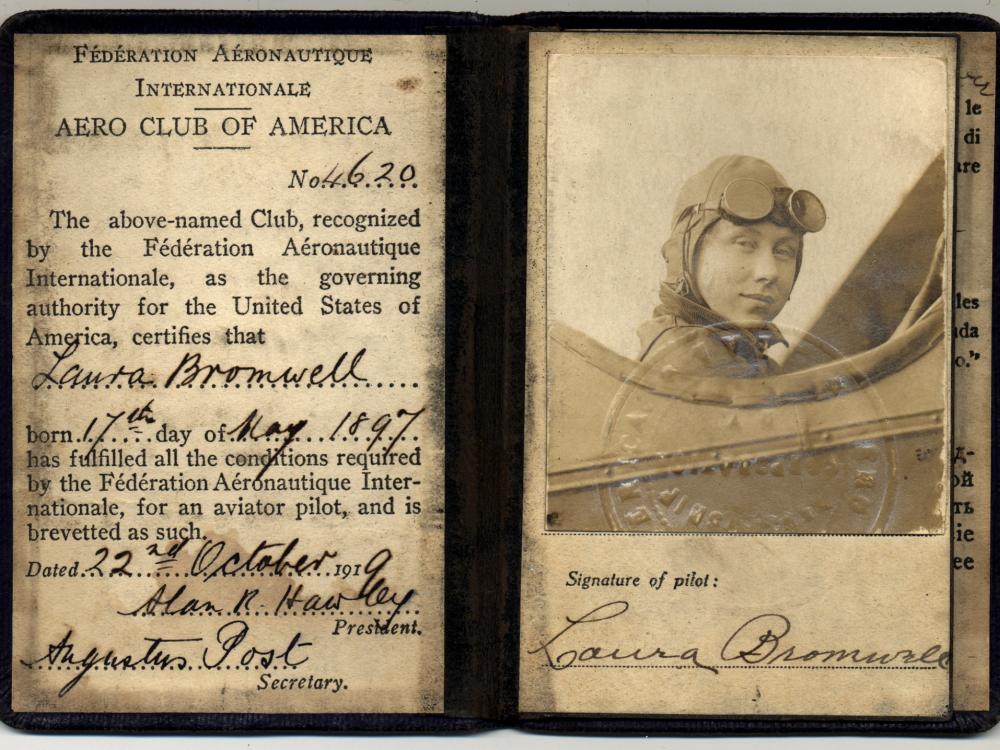

In her sepia-toned pilot’s license photo presented by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale and Aero Club of America, Laura Bromwell stares directly at the camera with her flight goggles perched atop her head. A natural daredevil, Bromell received the license at 22 years old in October 1919. Less than three years later, her career met a tragic end. Though short, her experience as a member of the aerial police force and exhibition pilot captures the inherent risk of flight and early opportunities for women serving in police aviation.

Born in 1897, Bromwell lived with her mother and seven siblings in Cincinnati, Ohio, following the death of her father in 1907. While working as a cashier in a restaurant, a customer challenged Bromwell to jump into the Ohio River from the Roebling Suspension Bridge. With $20 on the line, Bromwell accepted the stranger’s challenge. On a Sunday afternoon in July 1916, the nineteen-year-old successfully took the plunge, bobbing out of the water to live another day.

Though she earned fame from a Variety piece that highlighted the then-popular pastime of bridge-jumping, Bromwell struck out from Cincinnati to Virginia to sell war bonds by 1918. She had great success in this endeavor, selling $21,000 in Liberty bonds. The prize for selling the most Liberty bonds was an airplane ride, and Bromwell was determined to receive that honor. “I bought the last $1,000 bond myself so I could go up. But it was worth it,” Bromwell told the Boston Daily Globe. Her adventurous spirit relished the challenge and freedom of flight.

While one of the consistent barriers in learning to fly was cost, Bromwell’s timing was to her benefit. In spring of 1918, the New York Police Department established the Aviation Division Reserve as an unpaid, volunteer force. Utilizing volunteer aviators and war-surplus aircraft, the division was meant to be available during emergencies and trained several hundred people to fly or maintain aircraft. During her time as part of the NYPD Aviation Division Reserve, Bromwell made an impression, with her colleagues referring to her as their “lovely comrade.” In the first year of her flight career, Bromwell:

On August 21, 1920, Bromwell added to her list of accomplishments by breaking the record for air loops by female aviators. At the time, the record was held by a French woman who performed 25 complete loop turns. Determined to be a record holder, Bromwell climbed to 10,000 feet and counted a hundred loops while in the air. When she landed and the American Flying Club accredited her with only 87, Bromwell remarked, “I guess 87 is enough and will hold ‘em for a while,” according to the Middletown Transcript. After breaking the record, press eagerly requested photos. She is captured in the New-York Tribune.

Newspaper clipping titled 'Girl Flier Eager To Set Altitude Record for Women: Miss Laura -' showing an image of Bromwell after she broke the record for air loops by female aviators in 1920.

Bromwell, now known within the exhibition aviation field, agreed to have John C. Jackel serve as her manager for the 1921 season. Jackel negotiated with who The Billboard called “some of the most prominent fair and amusement men in the East” to set Bromwell up for shows to break her original record of 87 loops. Bromwell, now 23, took off from Curtiss Field, climbed to 8,000 feet, and performed 199 complete loops over a 1 hour 20 minute flight, shattering her own record from the previous year. Hitting a top speed of 135 miles per hour, she also set a new speed record for women aviators. Underscoring her law enforcement connection the Boston Globe reported, “Miss Bromwell wore the uniform of lieutenant in the New York Aerial Police Department.” Bromwell leveraged the publicity and continued participating in stunts and record attempts. When asked about her ambitions she said she wanted to hold the records for women for looping and for altitude and that she wished to fly across the continent and then ocean. “I am mad about airplanes,” Bromwell told the St Louis Post-Dispatch. in one interview. “They are my whole life. I don’t care a rap about matrimony…I am simply interested in records and the sport of the thing.”

Laura Bromwell’s ambitions were cut short when she died in a crash on June 5, 1921. Most accounts indicate the straps of the aircraft were not tight enough, causing Bromwell to lose touch of the rudder pedals and stall while in the loop. Though she was not one to publicize her personal life and had previously cast off the prospect of marriage, the New-York Tribune reported her fiancé, Mr. George Davis, was in attendance. When he learned she had died, he “collapsed and remained unconscious.” Bromwell’s New York funeral included, according to the New York Times, “masses of flowers and the presence of city officials and hundreds of her former comrades in the air service and the aviation section of the Police Reserve Corps.” Her body was sent to Toledo, Ohio, where an aviator escorted the hearse to an undertaking establishment. Services were held on June 11, 1921, and she was buried in Florence, Indiana.

Only 24 years old at the time of the fatal accident, Laura Bromwell never had the chance to see the combination of her passion and service take flight. By the end of the decade, Chief Charles Blair of the Beverly Hills (CA) Police Department deputized Elizabeth Lippincott McQueen as the world’s first aerial policewoman. While women continued to face barriers to access in the 20th century, Bromwell’s determined spirit and career as a member of the NYPD Aviation Reserves marked the beginning of women serving as invaluable members of the combined aviation and law enforcement communities.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.