Let's just hope it fits...

Aug 17, 2012

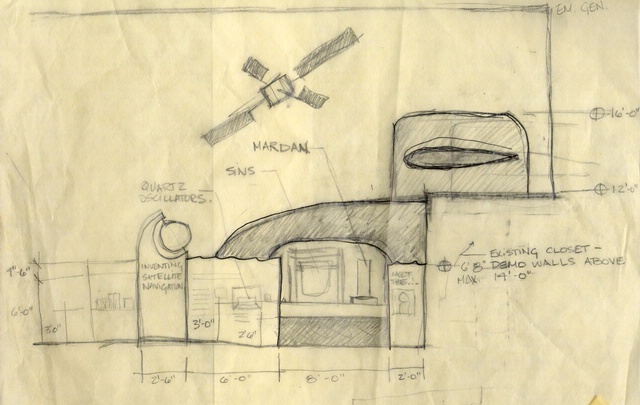

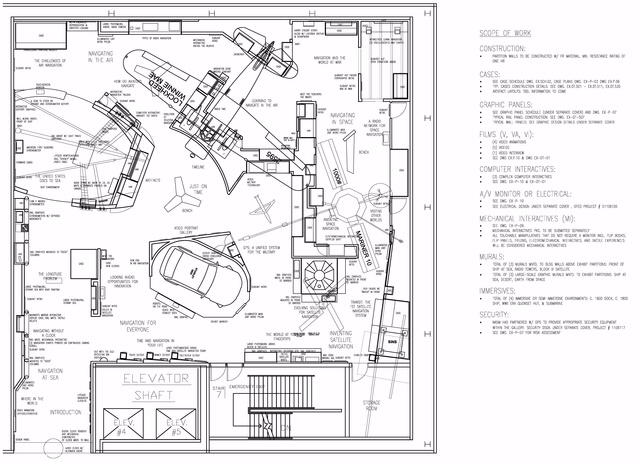

It takes a lot of people and effort to bring an exhibition from idea to reality. By the time I joined the exhibition team, Time and Navigation had been in development for over five years. The exhibit script was already written; the artifacts and images for display were already selected; the major features of the gallery were already imagined; the video content and interactive elements were identified. My mission as the exhibit designer was fairly simple and straight-forward: to transform the team’s words and ideas into a plan for a meaningful and accessible exhibition made of materials and space. There was only one problem—trying to make it all fit.

Here is a summary of the exhibit elements as they existed when I joined the team:

- 226 pages of exhibit text

- 7 major thematic sections containing 23 subunits

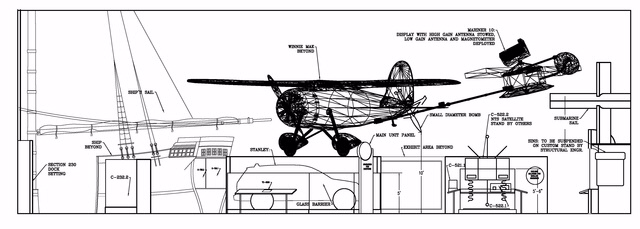

- Nearly 200 artifacts ranging in length from 1 inch (a chip-scale atomic clock) to 36 feet (a small airplane)

- 5 immersive environments

- 16 videos

- 13 interactive exhibits

And herein lies the problem: The gallery that will house all these elements is only 5,000 square feet. While this may seem like a lot, this space starts to look a lot smaller once you put an airplane, a car, and three satellites into it. Once these major artifacts are accounted for, there are still immersive environments to build that set the exhibition stage: the aft portion of a circa 1830 ship, part of a Cold War era submarine, a Quonset hut. And these only represent the primary experiences in 7 of the 23 content units, so there is a lot more stuff that still needs to fit. Ordinarily, a design problem of this nature would demand a highly creative process—thinking outside the box, so to speak. But in this case, I embraced a different approach. I embarked on the year-and-a-half long phase of my design career that I now refer to as “Thinking Inside the Box.”

You see, most of the remaining objects for display are what can be classified as "black boxes." To the curators and other people who know a thing or two about time and navigation, these boxes represent important moments in history or important developments in technology or have some other remarkable significance. But to me, the designer, they are the giant beige box, the small brown box, the gigantic tube of tin foil, or the cute little army green inner-tube robot that looks like a cartoon character. It is my job to present these objects beautifully and lovingly so visitors can see them as the curators do. So I design attractive glass boxes (display cases) to house them and accommodate their various and particular needs (climate, security, light levels, etc.) Each "black box," whether a cube, cylinder, or more complex shape, has to be measured and drawn and placed in a case layout with its associated label and sit on its own special piece of furniture (its mount). We test each case layout by gathering all the objects and labels for the case and placing them in their theoretical locations in their imaginary glass box. I modify the display case size and design as needed and then move on to the next case design. Meanwhile, our cabinet makers, mount makers, graphic designers, and graphic producers start making the components that we hope will all come together perfectly in the gallery when we start installing objects in the cases this winter.

This methodology works great, except when it doesn't. You see, not all the objects are currently in our collection. For example, we have plans to display the NIST-7, a 10'-6" atomic clock that just arrived from Boulder, Colorado. This "black box" is actually a long, shiny, metallic cylinder mounted on a long rectangular box that at some point in its history lost its covering. I have not been able to personally verify the object’s dimensions because it is just being uncrated today. Even though the folks from the National Institute of Standards and Timekeeping did provide me with measurements, the most basic rule of exhibit design is VERIFY ALL DIMENSIONS! However, we could not wait to have all the objects in hand before completing the design and commencing the year-long construction process. So I went ahead and designed the NIST-7 display case (and several others), which was built and placed in the gallery a month ago. The case is 11'-6" long, 5'-10" tall, and 2' deep—definitely large enough to display several humans, and hopefully a perfect fit for the NIST-7. I will know for certain very soon.

Several of my colleagues in the NIST-7 display case after it has been placed in the rough opening of the unfinished wall.

Since I started on the exhibition, we have distilled the script into a sharper, more concise narrative. We have taken out some objects and added others that better tell our story. We have omitted one environment and embellished others. All this has made the exhibition stronger and more focused. Now I watch and wait, as all my best laid plans are constructed and installed, just hoping that the exhibition comes together as I imagined it. And hoping that it all fits. Heidi Eitel is an exhibit designer at the National Air and Space Museum.

Related Topics

You may also like

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.