Mars Project: Wernher von Braun as a Science-Fiction Writer

Jan 22, 2021

By Michael Neufeld

The German-American rocket engineer Dr. Wernher von Braun is famous—or infamous—for his role in the Nazi V-2 rocket program and for his contributions to United States space programs. He was, I have argued, the most influential rocket engineer and space advocate of the twentieth century, but also one whose reputation will be forever tainted by his association with Nazi crimes against humanity in V-2 ballistic missile production. Von Braun certainly was multi-talented—he was a superb engineering manager, an excellent pilot, and a decent pianist. In the U.S., he became a national celebrity while speaking and writing about spaceflight. But we don’t think him as a science-fiction writer. It was not for want of trying. Von Braun wrote a novel, Mars Project, in America in the late 1940s and later exploited his fame to publish a novella about a Moon flight and an excerpt from his failed Mars work.

German science fiction certainly influenced von Braun in his youth, although we have few specifics. Born in 1912, he grew up during the ill-fated, democratic Weimar Republic, which lasted from 1918 to 1933. Like many German boys of his era, he read Kurd Lasswitz’s On Two Planets (1897), a work that paralleled H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, only in this case the Martians were benign. He seems to have read the popular, young-adult spaceflight novels of the 1920s, like those of Otto Willi Gail. Those works were stimulated by the explosion of serious spaceflight literature in Germany and Austria after the publication of Hermann Oberth’s The Rocket into Interplanetary Space (1923). It was Oberth’s work, however, and that of other advocates, that really shaped his enthusiasm. Influenced by the (mostly unsuccessful) attempts of some of them to educate the public about space travel through fiction, von Braun penned a short story in 1930, “Lunetta,” about a trip to Oberth’s proposed space station and space mirror. It is well written but lacks much of a plot and was never published.

Immersed in secret military rocket development for the entire Nazi period, it was not until after he landed in America in September 1945 that von Braun began to think about wrapping space advocacy in science fiction again. At Fort Bliss, outside El Paso, Texas, he was the leader of about 120 former members of the German Army rocket program helping U.S. Army Ordnance master guided missile technology. Postwar budget cutbacks soon meant that the Germans, quite in contrast to their wartime experience, had little work outside regular hours. Military money for space was minimal. Von Braun came to understand that he had to sell space travel to a skeptical American public if that was to change. There was a lot of science fiction in America, he noted to correspondents, but it was all in the Buck Rogers/Flash Gordon pulp fiction genre that had taken off in the 1930s. After his work and home life stabilized in 1947, he conceived the idea of writing a novel about the first human expedition to Mars based on intricately worked-out calculations and spaceship designs. It would be a scientific feasibility study wrapped in an exciting story. In the back would be a lengthy technical appendix that justified his scheme. He finished Mars Project in German in mid-1949 and it was translated into English by a West Virginia acquaintance of his mother. Some of his German colleagues at Fort Bliss helped him with the calculations.

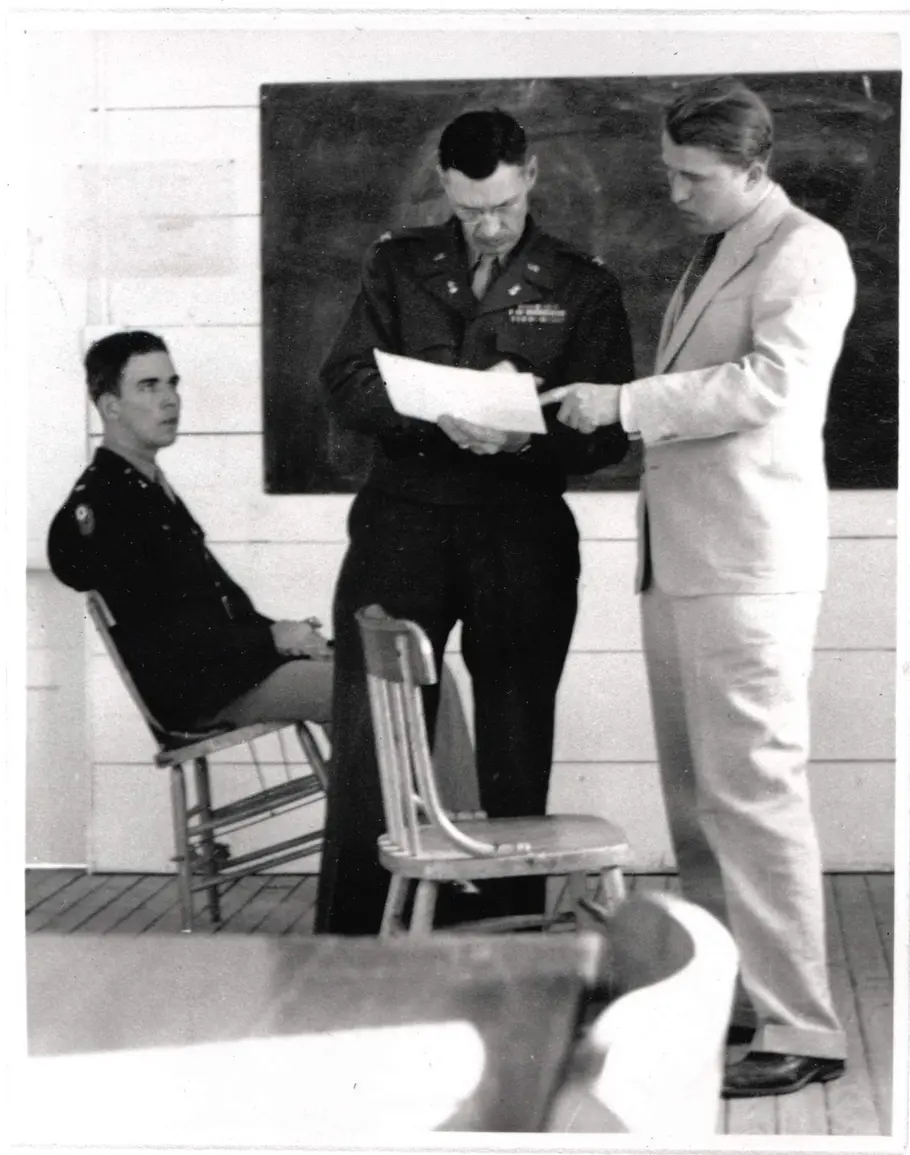

Von Braun (right) with his American superiors, Maj. James Hammill (left) and Col. Holger Toftoy (center) at Fort Bliss in the late 1940s.

The vision he laid out was gigantic, indeed grandiose: After a new 100-inch telescope in Earth orbit discovers evidence of intelligent life on the Red Planet, a ten-ship expedition is assembled through 950 launches of a three-stage, reusable booster more than double the weight and triple the thrust of the Apollo Saturn V Moon rocket of the 1960s. Three of the ships are “landing boats” with huge wings to glide in a Martian atmosphere thicker than we now know it to be. The expedition’s men (all men—von Braun was unthinkingly sexist) discover underground canals built to conserve the water on a dying planet, an updated version of Lasswitz’s Mars, based on astronomer Percival Lowell’s turn-of-the-century writings. The landing parties find an underground technological utopia inhabited by Martians very like us—God’s design, von Braun explains at one point, revealing his born-again Christian conversion in 1946.

The political context for his fictional Mars expedition is equally fascinating. Mars Project opens in 1980, after the United States of Earth, with its capital in Greenwich, Connecticut, conquers and occupies the Soviet bloc, aided by its space station—once again called Lunetta—dropping atomic bombs on Eurasian targets. While von Braun reveals his tendency to naïve technological utopianism in the Martian sections, his opening displays a conservative anti-Communism suited to the Cold War hysteria of 1949. His vision of World War III is, to put it plainly, a fantasy of a successful Blitzkrieg against the Soviet Union.

With great anticipation, von Braun sent the translation off to a New York literary agent in early 1950. It went nowhere. One editor commented: “Somewhere in this pulpy mass are the seeds of a good piece of science fiction, but I’m darned if I can get at them.” Something like 18 publishers rejected the book. Soon, a disappointed von Braun was consumed by the Army rocket development’s move to Huntsville, Alabama, followed by the sudden outbreak of the Korean War, which led to an urgent project to build the nuclear-armed Redstone ballistic missile.

Against the backdrop of a Chesley Bonestell painting for the first Collier’s issue in 1952, von Braun holds a model of the Walt Disney version of his rocket. The U.S. Army took this photo in 1955.

But all the effort that he put into the novel did pay off. In late 1951, Collier’s magazine decided to do a series of spaceflight issues dominated by von Braun’s vision. The first one, in March 1952, focused on von Braun’s ideas for a space station and the huge three-stage boosters needed to build it. The station had many uses, but his primary argument was that it would dominate the Soviet Union with nuclear weapons. Von Braun’s sudden fame led a German publisher to put out the technical appendix as a small book, Das Marsprojekt, in late 1952; the University of Illinois Press released a revised version as The Mars Project in 1953. Remarkably, it’s still in print. (His German publisher also had a ghostwriter completely revise the novel, which von Braun hated so much it was eventually published under the German author’s name.) A heavily illustrated, non-fiction version of his full, ten-ship Mars expedition appeared in the last Collier’s space issue in 1954. After other rocket engineers criticized his gigantomania (love of huge projects), he published a slimmed-down, three-ship version in The Exploration of Mars in 1956.

By then, Walt Disney had made von Braun into a TV star. After the Soviet Sputnik in 1957 and the first successful U.S. satellite launch in 1958, he was presented with many new, lucrative opportunities. This Week magazine ran his four-part fictional story, “First Men to the Moon,” in late 1958 and early 1959, which was padded out with popular science material to make a short book in 1960. The magazine then published an excerpt from his depiction of a Martian utopia. At that point, he and his group had already transferred to NASA, where he was consumed by the Moon race and never tried writing fiction again.

The original novel finally appeared in 2006, 29 years after von Braun’s death. A small Canadian space publisher brought it out as Project Mars, to distinguish it from The Mars Project. While I wouldn’t recommend it as great fiction, it certainly is a revealing portrait of von Braun’s mind and vision of the future in the late 1940s.

Michael J. Neufeld is a senior curator in the Museum’s Space History Department and is author of The Rocket and the Reich (1995) and Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War (2007).

Related Topics

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.