NASA’s Early Stand on Women Astronauts: “No Present Plans to Include Women on Space Flights”

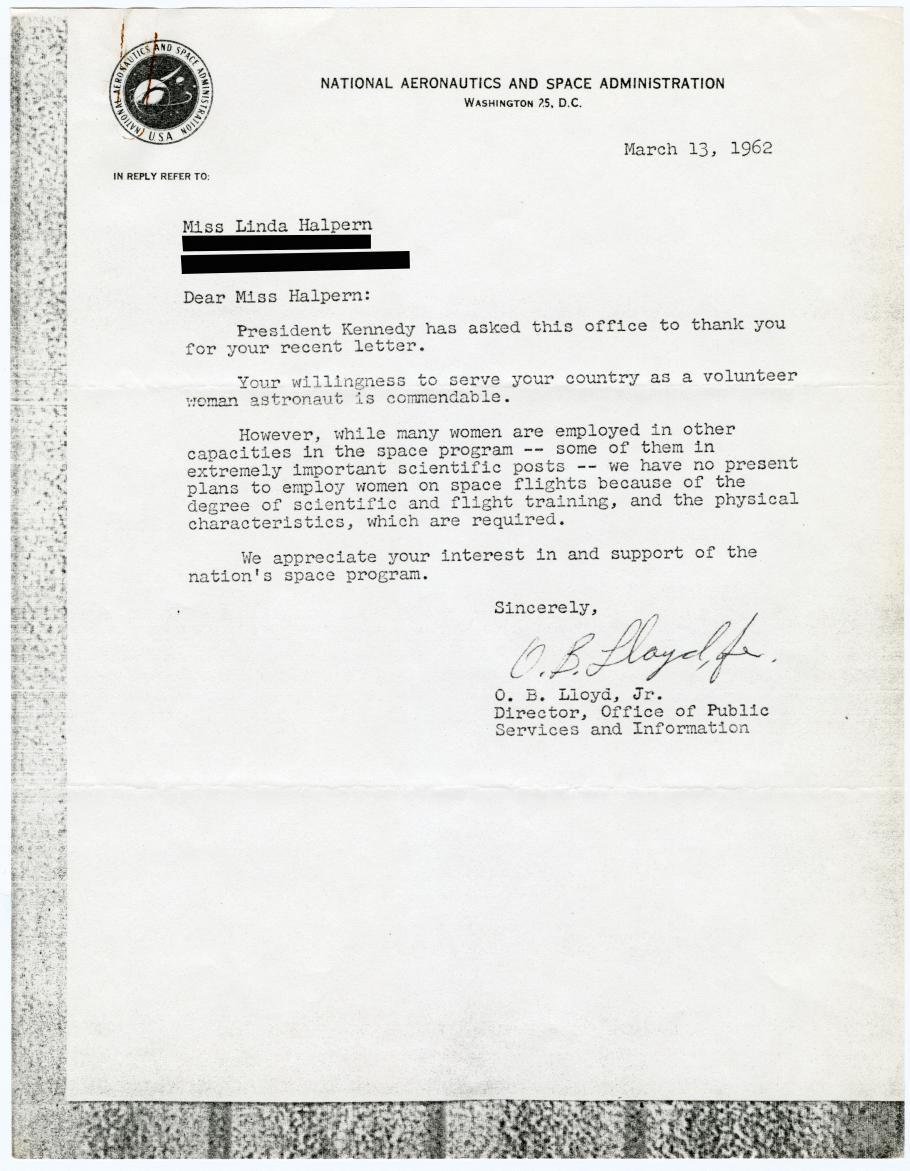

In 1962, young Linda Halpern decided to fulfill a school assignment by inquiring about how she could pursue a dream. Required to write a letter for a grade-school class, Ms. Halpern addressed hers to President John F. Kennedy, asking what she would need to do to become an astronaut. The reply that came from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was not terribly encouraging. “We have no present plans to include women on space flights,” it read, “because of the degree of scientific and flight training, and the physical characteristics, which are required.” But Halpern’s letter highlights an historical moment when the early years of the space age overlapped with the beginnings of the second wave of the American women’s movement. The letter has been preserved for decades in the files of Dr. Sally K. Ride, America’s first woman in space, whose personal papers were acquired by the Museum’s Archives in 2015.

Halpern’s decision to ask about a girl becoming an astronaut tapped into the cultural excitement about human space flights in the early 1960s. And her question about whether women would join human space flights had been actively explored in the late 1950s. In fact, before any person had flown in space, some researchers had been exploring whether women might actually be better suited for space flights than men were. Scientists knew that women, as smaller beings on average, require less food, water, and oxygen, which was an advantage when packing a traveler and supplies into a small spacecraft. Women outperformed men in isolation tests and, on average, had better cardiovascular health. W. Randolph “Randy” Lovelace, the researcher and flight surgeon who performed the medical evaluations on NASA’s first male astronaut candidates, also ran a privately-funded program examining women pilots to see how they would fare under same testing regimen. Lovelace invited 25 female pilots to take the same tests at his Albuquerque, New Mexico facility that had been used to screen male military pilots for NASA’s Project Mercury selection process. Jerrie Cobb and 12 other women pilots passed—and were ready for more advanced testing when Lovelace canceled the program in 1961.

Jerrie Cobb succeeded in having House subcommittee hearings held in the summer of 1962, investigating whether NASA was discriminating on the basis of sex, but the results were not what she hoped. Cobb and Jane Hart testified about the women’s successes. But Jacqueline Cochran, the record-setting aviatrix who had funded the Lovelace tests, testified against continuing the program at that time (hoping that it could be reconstituted later, under her leadership). More important, legal protections for women did not yet exist. Sex discrimination had been identified in 1962 but it would not become illegal until the 1964 Civil Rights Act. At this time, job ads in newspapers ran under separate categories for men and women. Feminist political organizations did not exist yet to support the women. And the Congressional representatives listening to testimony were starstruck to meet NASA’s newest orbital fliers: astronauts John Glenn and Scott Carpenter. NASA’s representatives argued that 1962 was not a time for experimentation, perhaps astronaut qualifications should be even more demanding in the future. Women could not become astronauts because the early requirements for NASA’s astronaut corps had gender restrictions invisibly embedded in them. Astronaut candidates needed to be graduates of military test piloting schools. But military flying had been closed to women since the disbandment of the Women Airforce Service Pilots in 1944, just before the end of World War II. Indeed, even if NASA’s administration had been willing to think more broadly about astronaut qualifications, once real human space flights had begun, including women had become far less likely. Within weeks of the first manned space flights (Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s single orbit on April 12, 1961 and American astronaut Alan Shepard’s suborbital flight on May 5, 1961), President Kennedy put the United States on the path to the Moon in a speech to a joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961. Thus ended any moment of spaceflight experimentation that might have existed in the U.S.; NASA focused on preparing for a lunar landing by the decade’s end. In that context, questions about whether women could be astronauts became perceived as potential distractions. (After Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space in 1963, the idea of including American women in space flights was dismissed as a political stunt.) This was the moment, then, in the spring of 1962, as Cobb was campaigning around D.C., hoping to restart the Lovelace testing and eventually sparking the House subcommittee hearings, when Halpern’s letter to JFK arrived at the White House, asking about how a girl could become an astronaut.

Women would not become a part of the U.S. astronaut corps until 1978, when NASA announced the first class of astronaut candidates that included women, African-American men, and an Asian-American man. One of the six women in that group of space shuttle astronauts was Dr. Sally K. Ride, who became the first American woman in space. Meanwhile, Halpern grew up to have a successful career as an attorney, serving with distinction in the Texas Attorney General’s office. In 1983, when Ride flew into space aboard STS-7, Halpern was working as a trial attorney for the U.S. Department of Justice in Washington, DC. She sent NASA’s letter to Dr. Ride to let her know that she was fulfilling so many young girls’ long-deferred dreams of spaceflight. Dr. Ride kept it in her files for the rest of her life.

Related Topics

You may also like

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.