Feb 26, 2016

By Matthew Shindell

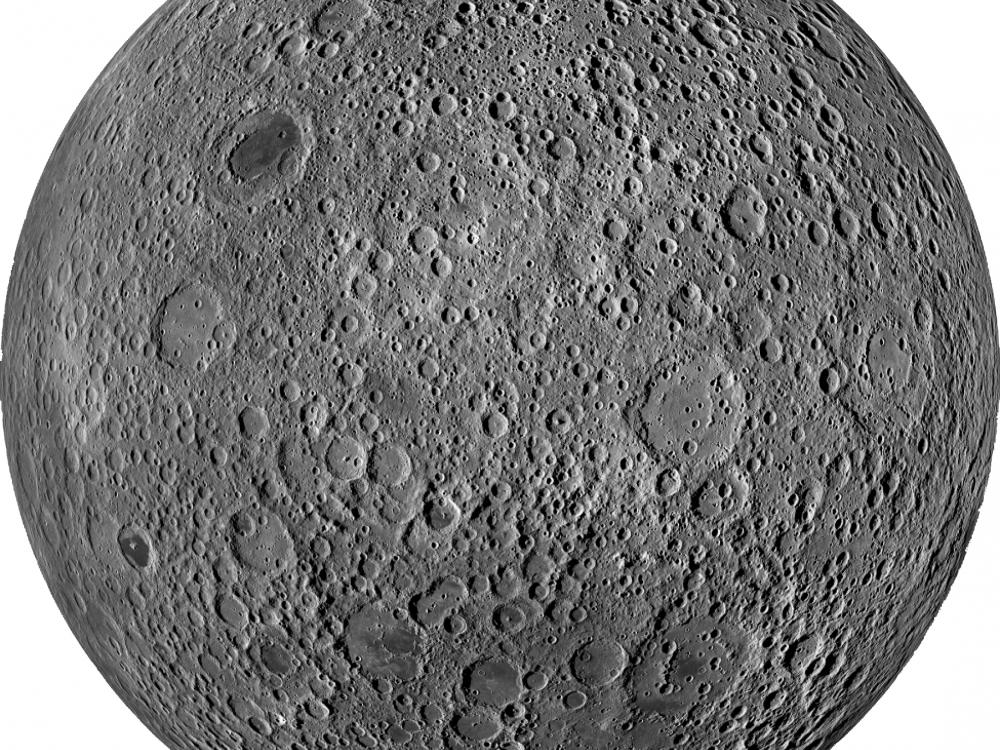

Scientific images can rival those of the most talented artists, a fact that is now on display in A New Moon Rises at our Museum in Washington, DC. Take, for example, an image of Reiner Gamma, a beautiful and strange feature on the Moon that looks as though a tadpole has been painted across the flat surface of Oceanus Procellarum. The image demonstrates the phenomenon of lunar swirls – bright patterns that some scientists believe may result from the solar wind striking the lunar soil. A localized magnetic field anomaly may have given this swirl its peculiar shape. The photo is densely packed with scientific information. And it is as visually interesting as it is informative. The same can be said of an image of the central peaks of Plaskett Crater, which rise mountainously to more than 1.9 kilometers (1.2 miles) above the shadowed, cratered floor. A nature photographer could hardly ask for a more dramatic landscape.

At the heart of this exhibition is a scientific instrument—the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC). LROC is in fact a system of three separate cameras, two telescopic Narrow Angle Cameras (NACs), and one Wide Angle Camera (WAC), that together have taken the highest resolution photos of the Moon to date and have mapped its surface in visible, near infrared, and ultraviolet light. These images are contributing to a new understanding of the Moon and its geology. But surrounded by the images these cameras have produced of the Moon and its dramatically cratered and ridged features, elegantly framed and hung like fine art photography on the walls of the gallery, one is struck by just how interesting—in a way simultaneously familiar and alien—the lunar landscape is. It is art as much as it is science. Photography and lunar exploration have a long relationship. When the Apollo astronauts landed on the Moon, they carried with them Hasselblad cameras. They used these cameras to document their activities on the Moon, snapping pictures that have become some of the most iconic still images of the space race. They also used photography to provide contextual information for scientists about the areas where they collected the lunar rocks they brought back with them. But astronauts didn’t take the first pictures on the Moon. By the time of the 1969 Apollo 11 landing, when humans set foot on the Moon for the first time, more than 100,000 pictures of the Moon had already been sent back. Beginning with the Soviet 1959 Luna 3 mission, a host of robotic spacecraft had crashed into, landed on, and orbited the Moon, radioing photographs back to Earth so the Moon could be studied and mapped. Captured on film, processed, and scanned automatically onboard the spacecraft for transmission, or captured using television cameras, these images were key to identifying interesting and safe landing sites for the astronauts to explore. Some of the probes even filmed or took pictures from a similar height to that of the human eye, so astronauts and scientists would have some idea of the landscape they would see when they walked out of the Lunar Module.

Still, even with such a vast collection of images, some geologists and planetary scientists felt that a human with a camera would be able to identify interesting features that a robotic craft might miss. The Apollo 8 astronauts, who photographed the Moon from the spacecraft, recognized that they had an advantage over the “programed systems of unmanned spacecraft” that had come before them: “This was an opportunity,” the astronauts reported after their flight, “for the observation of another planetary surface in a situation that combined continuously varying viewing geometry and lighting with the exceptional dynamic range and color discrimination of the human eye. Add to this the potential of the experienced human mind for both objective and interpretive selection of data to be recorded.” Geologists back home on Earth agreed. When the geologist Thomas A. Mutch wrote the very first textbook in the new field of planetary geology, Geology of the Moon: A Stratigraphic View, he collected together the most scientifically interesting photos that had been captured up through Apollo 11. But he began the book not with a picture taken on the Moon, but one taken of the Moon from Earth almost a decade before the Soviet launch of Sputnik ushered in the Space Age. It was the photographer Ansel Adams’ photograph, Autumn Moon, The High Sierra from Glacier Point that adorned the title page of Mutch’s book. Using Adams’ photograph, Mutch made the visual argument that the Moon was the next great frontier for human geologists to explore – a terrain whose geological history could be told in the same way as that of the American West. The photos on display now in A New Moon Rises bear out Mutch’s prediction that geologists exploring the Moon can reveal interesting things about its history. Just like the images taken by the pre-Apollo spacecraft, these images are being used to identify possible landing sites for future manned missions. But rather than waiting for humans to get to the Moon to perform geologic exploration, the LROC cameras are being used today by geologists on Earth to map the minerals in the lunar surface; analyze the lunar soil; map and characterize lunar surface features; and to refine a chronology of the Moon’s geologic history. With higher resolution and no reliance on film—the cameras use charge-coupled devices (CCD’s), the same technology used in digital cameras and smartphones—scientists are able to collect and compile hundreds of thousands of images, each containing a wealth of geologic information. Along the way, they are also producing stunning images of the Moon the likes of which Ansel Adams may only have dreamed.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.