Pioneering Aerial Archeology by Charles and Anne Lindbergh

Jun 16, 2016

By Dorothy Cochrane

Jun 16, 2016

By Dorothy Cochrane

On October 7, 1929, Anne Morrow Lindbergh gazed out the window of a Sikorsky S-38 flying boat, entranced by the view before her: gleaming stone structures only recently freed from the thick tropical vegetation of the Yucatan peninsula in Mexico—Chichén Itzá, a remnant of the Mayan civilization that thrived there between 750 and 1200 AD. Her husband Charles A. Lindbergh piloted the aircraft that skimmed just above the ruins and treetop canopy. Archeologists from the Carnegie Institution of Washington, who were actively excavating other Mayan sites in dense jungle, accompanied them and were pleased to behold their first aerial sight of the great Mesoamerican civilization. The Lindberghs also brought along a popular camera, the Graflex RB Series C model now displayed at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, with which they took the first aerial photographs of Mayan sites in British Honduras (now Belize), Guatemala, and Mexico, as well as ancestral Puebloan sites in southwestern United States. Their milestone photography illuminated the details of pre-Columbian societies and became permanent aerial records of these settlements.

How did the Lindberghs get involved in the emerging field of aerial archaeology? In February 1929, during his inaugural Pan American airmail flight from Havana to the Panama Canal, Charles flew inland from the Gulf of Honduras and noticed unusual mounds and man-made structures protruding from the jungle. Back in Washington, DC, he contacted Secretary Abbot of the Smithsonian Institution who sent him to President J.C. Merriam of the Carnegie Institution that was conducting archeological studies at several Native American culture sites. Merriam referred Charles to Dr. Alfred V. Kidder who had active digs at New Mexico ruins of the ancestral Puebloans (859 AD and 1250 AD). Chaco Canyon was first “discovered’ by the white trader Josiah Gregg in 1832; Kidder was excavating its Great Houses that served as community centers for an ancient culture that, according to oral tradition, was sophisticated and complex. Lindbergh said he would be flying near the area that summer and agreed to photograph sites from the air.

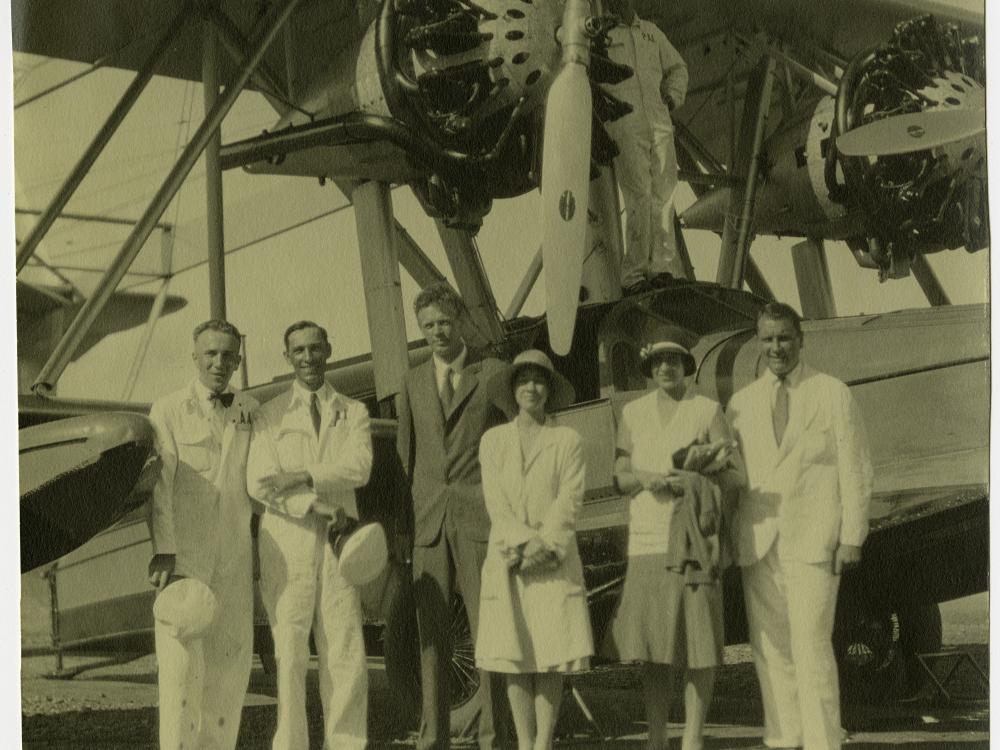

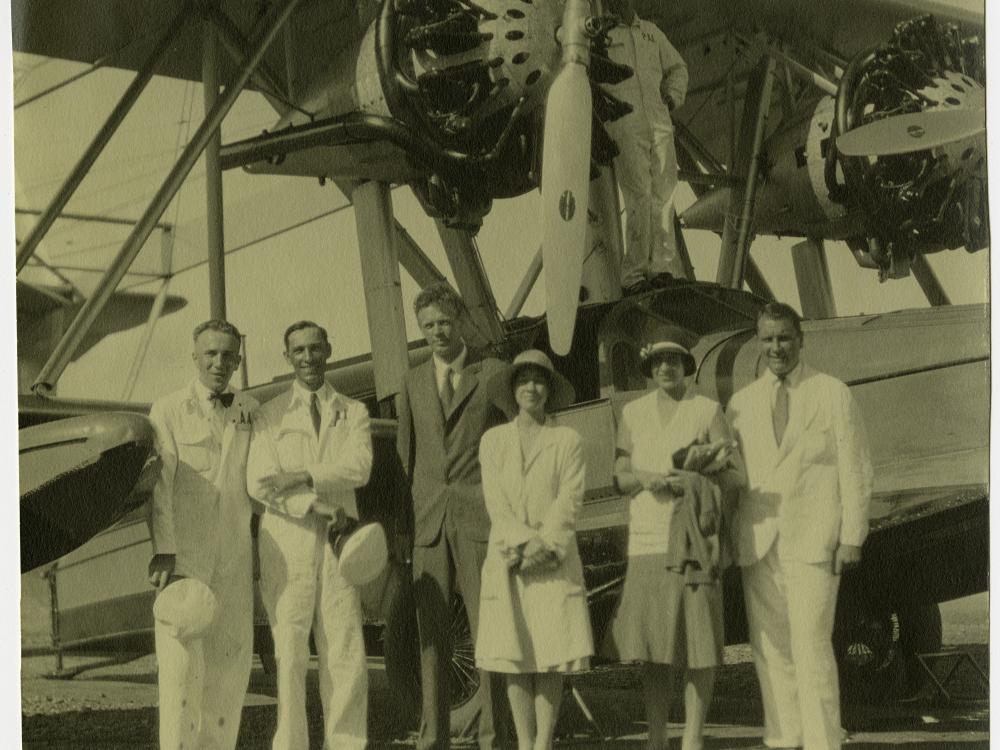

Charles and Anne Lindbergh (center) with Betty and Juan Trippe (right) and Pan American Airways personnel by a PAA S-38 amphibian at France Field, Canal Zone (Panama), September 29, 1929. Charles and Anne used this or another S-38 for their aerial archeology flights over Mayan ruins in British Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico. Image: From the National Air and Space Museum Archives’ Mother Tusch Collection

Following their marriage in June 1929, Charles and Anne Lindbergh embarked on a cross-country flight from Roosevelt Field to Los Angeles in a Curtiss Falcon, landing at the depots and airports for the Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT) rail-air, 48-hour, coast-to-coast passenger service for which Charles was technical advisor. En route back east they used their Graflex RB Series C to make the first aerial map of Arizona’s Canyon de Chelly and New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon and Pecos area. With Charles as her flight instructor, Anne was already able to hold a steady course in the open-cockpit Falcon so they took turns flying and photographing. Together they shot more than 100 photographs of ancestral Puebloan ruins and another 100 in the Four Corners area (Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado) in seven days. From their aircraft perch, they spied the remains of cliff dwellings so well hidden near the top of a canyon wall that they were unknown to the Carnegie team. They carefully photographed the site (now known as Beehive Ruin) so that it could be relocated later. Many of the Lindbergh images from Canyon de Chelly were the first known aerial photographs for these locations.

The Graflex RB Series C was part of a revered line of single-lens reflex cameras that offered an exact reflected image of the subject in its ground glass viewer and a focal plane shutter with exposure speeds up to 1/1000th of a second. This particular Graflex featured a Taylor-Hobson lens with a large aperture that aided in focus control. Therefore, though this was a hand-held camera, it produced sharp images from the open front windows of the moving S-38. A flip up viewfinder allowed the Lindberghs to shoot at eye level while seated in the plane (normal stance was waist high with an open focusing hood).

Left: Flip up viewfinder and the Taylor-Hobson with Cooke astigmatic lens.

Right: The Graflex RB Series C in the configuration used by the Lindberghs for these photographs – the viewfinder is at the top and the 12-exposure film pack is at the back.

The camera with extended focusing hood.

The Lindberghs’ pioneering aerial archaeology, documenting the area in relatively pristine condition, stood as the only aerial record until the 1960s. The collection held surprises including the first images of the only prehistoric road system in North America; later infrared photography revealed the ancestral Puebloans had cut more than 644 kilometers (400 miles) of straight roads through the rough terrain. Aerial images of the Pueblo Bonito great house of 600 rooms and “The Threatening Rock” that towered over it proved their worth when, in 1941, the sandstone rock pillar fell onto the ruins, destroying 65 excavated rooms. Based on this successful mission, Kidder and the Lindberghs agreed to continue the aerial photography at Carnegie’s Mayan dig sites in the fall when they would be in the area for Pan American Airways.

On September 20, 1929, Charles and Anne departed Dinner Key, Miami in a Fokker 10A Trimotor with Pan American President Juan Trippe and his wife Betty for a 11,265 kilometer (7,000 mile) Pan American Airways airmail and marketing tour around the Caribbean Sea. In Havana, they switched to an S-38, an eight-seat amphibian designed by Igor Sikorsky, often called an ugly duckling due to its snout nose, boat-shaped wooden hull, twin tails set on high outriggers, and cluttered appearance of struts and wires. Though water splashed up on the cockpit windows during takeoff, it was the right choice for overwater flights to islands and inlands where airfields were scarce.

With Charles, Anne, and a Pan Am employee in one S-38 and the Trippes in another, the group island hopped from Puerto Rico, Haiti, the Virgin Islands, Port of Spain to Paramaribo, Dutch Guiana, and the coasts of South and Central America. The Lindberghs then flew the S-38 NC142M to Belize, British Honduras, to rendezvous with Dr. Kidder, happy to leave the crowds behind.

The group spent five days surveying remote areas in British Honduras, Guatemala, and the states of Campeche, Quintana Roo and Yucatan in the southern Mexico peninsula. Flying between 152 and 457 meters (500 and 1,500 feet) above the canopy of trees gave them enough height to detect elevation changes at eye level, possibly signifying something worth investigating, while the “cruising speed” of 145 kph (90 mph) allowed for close inspection into the vegetation. With Charles at the controls, Anne was a constant set of eyes seated either in the front right seat or in the cabin; both of them photographed visible ruins, promising sites, and the geographical features of swamps, rivers, and terrain. On October 6, Anne and archeologist Oliver Ricketson, Jr. flew with Charles for five and a half hours, covering 731 kilometers (454 miles). They headed west along the Belize River looking for ruins of Yaxha but, unable to find them, they flew on to the ruins at Uaxactun, the oldest known Mayan city that Ricketson had been excavating for four years. En route they set “records,” flying 23 kilometers (14 miles) southwest from Tikal to Uaxactun in six minutes, a trip that took a day by pack mule, and reducing another three-day mule ride in dense, bug-infested vegetation to an hour by air. Turning north along a 644-kilometer (400-mile) course, they constantly verified or corrected data and maps and took photographs; when they saw the Gulf of Mexico they turned west to Merida.

The next day, Dr. Kidder joined them for a four-hour flight over Chichén Itzá, where Anne or Charles took the finest extant photographs of the site including El Castillo, Temple of the Warriors, the large Ball Court, and El Caracol, and the return to Belize. They flew up and down the peninsula on the 8th and 9th searching for other sites and set out on the 10th to look for an ancient masonry causeway but were unable to find it. Bidding farewell to Kidder and Ricketson, the Lindberghs flew on to Miami, never to return to this project. In her diary, Anne wrote her testament to the lost world of the Mayans:

We had one exciting day of finding mounds of ruins in the Quintana Roo country south of Yucatan. The thick jungle growth trails over mounds and masonry, like a blanket of snow; one can see nothing but an outline, usually. But it gives one a weird feeling to see a bit of wall – white masonry sticking nobly out of the tangling jungle, still fighting for breath. Unspeakably alone and majestic and desolate – the mark of a great civilization gone.

The Lindbergh Carnegie images proved the value of aviation and aerial photography to archeological research in remote areas—Carnegie archeologists now had detailed aerial evidence of two great Native American cultures to connect with ground excavation. The Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, New Mexico, houses portions of the Lindbergh Southwest images and currently displays an exhibit juxtaposing Lindbergh and recent aerial photographs of the area. The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University holds images transferred from the former Carnegie Institution and a limited number of images are in the Charles A. Lindbergh collection at Yale University Library. The Graflex RB Series C camera, donated to the Museum by Juan Trippe, is in the aerial photographic case at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

In the center of the photograph, nearly at the foot of a 183-meter (600-foot) canyon wall, is a recessed cliff dwelling of ancestral Puebloans known as White House Ruin, then an ongoing excavation site of the Carnegie Institution and later the subject of a famous 1941 photograph by Ansel Adams. Canyon de Chelly, Arizona.

Maya ruins at Chichén Itzá, Yucatan, Mexico. <br />

Top, from left to right: The Great Ball Court was used for sporting events and, at 146-meters (480-feet) long, it is the largest court in Mesoamerica. <br />

The Temple of Kukulan was built for astronomical purposes. <br />

The Temple of the Warriors was built for large gatherings.<br />

In the foreground: El Caracol (Spanish for snail) is a rounded structure and possible observatory as it aligns with Venus.

Yucatan, Mexico<br />

Left: Temple of the Warriors or Temple of a Thousand Columns consists of four-step platforms surrounded by round and square columns of Toltec Warrior statues.<br />

Right: The Temple of Kukulan (The Feathered Serpent God) or El Castillo (Spanish for pyramid), built in the 11th-13th centuries), is 24 meters (79 feet) high, has 365 steps, and bears cosmological symbolism.<br />

The Carnegie Institution camp is to the left of cleared but un-excavated ruins in foreground.<br />

Uaxactun, Guatemala

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.