Jan 02, 2017

By James David

After decades of unsuccessful attempts to gain access, the public is now finally able to review the President’s Daily Briefs (PDBs) from the Kennedy through Ford administrations. The collection was released in 2015 and 2016 and sheds lights on the intelligence and analysis the presidents received at the time. They are posted on the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) website and are available to anyone to read.

No briefing has been released in its entirety. During the declassification review, portions that were deemed too sensitive to release were redacted. In some cases, entire entries are missing while in others just parts are. I recently explored these briefings and released an Electronic Briefing Book where I share my impressions of the briefings and provide additional historical context.

The CIA published the first of these intelligence reports on June 17, 1961 for President John F. Kennedy, and ever since they have been published six days a week. It is important to note that the briefings have never been the sole source of intelligence for the presidents. Through the years, there have been many other reports that they have seen. Some have been written by the CIA, while others by different agencies or interagency bodies. Also, presidents have received a substantial amount of intelligence in briefings from the national security advisor, director of central intelligence, and other high level officials.

Briefings have always been written specifically for the president and contained intelligence and analysis on current and future national security issues. Their format, length, and content have been tailored to meet the requirements of each president. They are one of the few intelligence reports that have used all types of classified information and have no classification limit. Information obtained from human sources, satellites, ships, aircraft, ground stations, and open sources such as newspapers and radio broadcasts is included. Briefings have always had the most restricted distribution of any intelligence report. Presidents have designated other officials entitled to receive copies, which frequently has included the vice president, secretaries of state and defense, and the national security advisor.

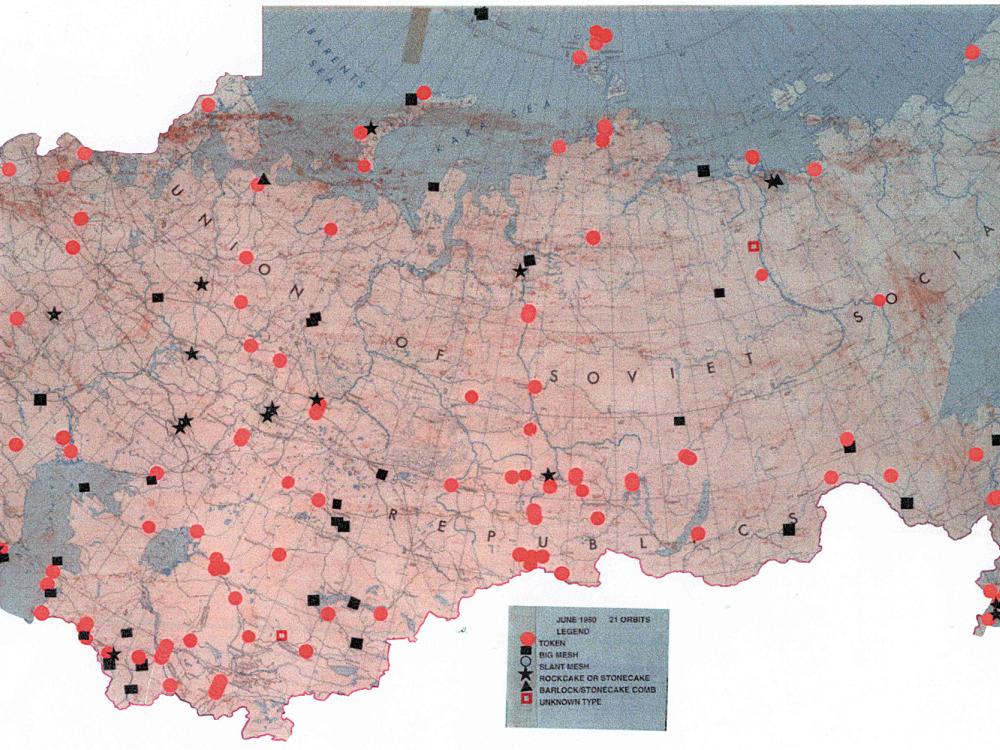

The briefings from the four administrations recently released averaged between six and 10 pages in length. Individual entries on a single topic were concise (varying between one paragraph and one page) and occasionally included a photograph, map, or illustration. Not surprisingly, entries on the Soviet Union were most numerous followed by those on Vietnam and China.

Soviet missile programs received extensive coverage. This was particularly true for intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) that could destroy the United States with their nuclear warheads. Throughout the Cold War, there was no more important issue than the strategic nuclear arms race between the two nations. The briefings document the development, testing, and deployment of second- and third-generation ICBMs that finally achieved quantitative parity with the U.S. ICBM forces in the early 1970s and qualitative parity subsequently. They also disclose the slower development, testing, and deployment of long-range SLBMS and the submarines to carry them. In 1972, the United States and the USSR signed the first Strategic Arms Limitation Agreement (SALT 1) that limited strategic offensive nuclear forces in certain respects. Thereafter, the briefings often addressed Soviet compliance and improvements to these forces not prohibited by the treaty. Soviet anti-ballistic missile (ABM) programs were also a frequent subject in briefings. ABMs could destroy U.S. ICBMs and SLBMs and greatly alter the strategic balance between the two superpowers. The two nations signed the ABM Treaty at the same time as SALT 1, which limited both to a small number of interceptors that would not affect the strategic balance. Once again, subsequent briefings often covered Soviet compliance and efforts to develop improved ABMS.

Soviet space programs were also a common topic in briefings. Their human spaceflight program accomplishments and problems were often addressed. This was particularly true with respect to the question of whether they had a manned lunar landing program and, if so, whether it was competitive with Apollo. This is not surprising considering the tremendous national prestige that would be earned by being the first to land humans on the Moon. The intense and very visible competition between the two nations in space also encompassed a wide range of other programs. As a result, Soviet lunar and planetary probes, weather satellites, communications satellites, and other applications satellites were commonly addressed. The USSR also had a covert military space program to conduct reconnaissance, anti-satellite operations, and other tasks. These were threats to U.S. national security and were covered extensively.

I recently wrote an Electronic Briefing Book, posted on the National Security Archive website, which contains a selection of the hundreds of entries on the Soviet missile and space programs. Because the entries are concise, I frequently added information to give them a larger context and background. It was a fascinating project to see what Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, and Ford read on these issues. The information they learned from them affected their decision making on a wide range of policies.

It is hoped that the public takes advantage of the release of the briefings to review them and learn of their impact on our history during the Cold War.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.