Transforming the Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight Gallery

Oct 01, 2019

By Dorothy Cochrane

Oct 01, 2019

By Dorothy Cochrane

The Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight Gallery, home of the Lindberghs, Earhart, Doolittle, and Piper, among many other pioneers, closes on October 7 as part of the transformation of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. But it will be back in 2022!

The original Pioneers of Flight gallery opened on July 1, 1976, when our building on the National Mall first opened. The new National Air and Space Museum gave the public access to aerospace artifacts that so many people had actually witnessed making history—and this personal connection is an important reason for this Museum’s ultimate success. When the museum first opened, many people had their own memories of Lindbergh soloing the Atlantic in 1927 and millions more watched Neil Armstrong step onto the Moon via their television sets in 1969. The objects were and continue to be tangible pieces of “recent” history — after all, aviation and spaceflight were 20th century inventions.

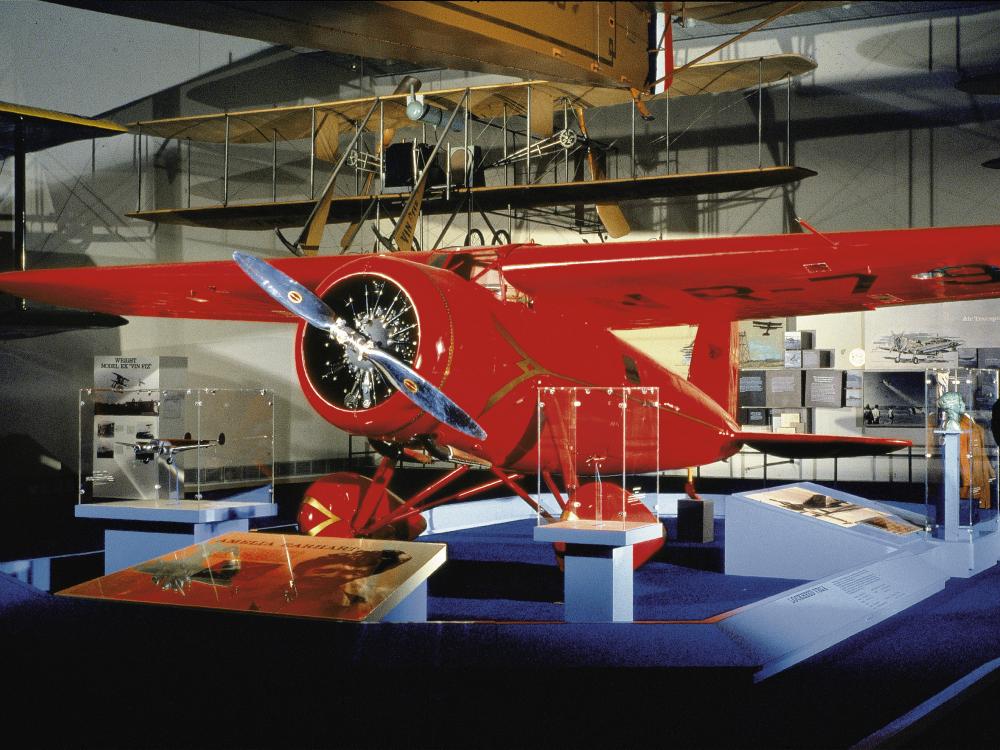

Pioneers of Flight was one of many galleries that showcased aviation pioneers, but it focused on its own specific time frame. Museum curators initially conceived Pioneers of Flight as a second-tier Milestones of Flight), the gallery that presented the most iconic and historic aerospace artifacts of the Smithsonian’s collections, like the 1903 Wright Flyer, the Ryan NYP Spirit of St. Louis, and Mercury Friendship 7 and Apollo 11 command module Columbia. Pioneers’ location in Gallery 208 was offset on the second floor with its mezzanine overlooking Milestones, thus offering a natural affinity and progression between the two galleries. Don Lopez, assistant director for aeronautics, selected the aircraft for the gallery, in consultation with Aeronautics Department curators, choosing specific ones that flew in the 1920s and 1930s. For him and his contemporaries, this was the time that aviation came of age after the initial years of experimentation in aviation. In the exciting 1920s and difficult but breathtaking 1930s, aviation proved itself useful, and became integral to society and a leader in technology and design. Lopez’s Pioneers of Flight gallery reflected many of his 1920s childhood memories and his delight in following aviators into the air (Lopez became an U.S. Air Force ace in World War II). The gallery concentrated on three areas:

Taking the lead from Public Law 722, which established the National Air Museum in 1946 to “collect, preserve, and display aeronautical equipment of historical interest and significance,” among other things, the original Pioneers of Flight gallery focused on the aircraft. Its spotlight was on each airplane on display, its primary accomplishment and, in varying degrees, specific pilots. The display surrounding each aircraft offered a small selection of supporting artifacts; labels were direct and concise.

Over the next 30 years, aircraft and small exhibits were moved into and out of the gallery, and the emphasis shifted to “pioneers” rather than a specific time frame. The most groundbreaking addition was Black Wings, installed in 1983 as the first and only exhibit on African American aviation pioneers in a major U.S. museum. Its content, from Bessie Coleman, the first African American woman to earn a pilot’s license, to African American astronauts, relied heavily on two curator’s contacts with early African American pilots or their families for research in personal archives andoral histories, as well as academic, military, and popular literature. For many years, the west wall of the gallery served as a rotating biographical unit, featuring pilots, engineers, aerodynamicists, and more.

The first helicopter to fly around the world, a Bell 206 LongRanger flown by H. Ross Perot Jr. and Jay Coburn, was installed in 1983. When the Museum’s Balloons and Airships gallery closed in 1989, the replica scale model of the 1783 Montgolfier balloon and the stratospheric balloon gondola Explorer II from 1935 moved to Pioneers. In 1993, in a controversial decision, the Extra 260, a modern aerobatic aircraft, was added, expanding the “pioneers” theme to include the first female pilot to win a U.S. national aerobatic championship, Patty Wagstaff.

Patty Wagstaff's Extra 260 in Pioneers of Flight in 2006.

In 2003, after the opening of our Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, we took a close look at the original aviation galleries at the Museum in DC, which looked old and out of date. Where and how to start an upgrade program? Happily, a timely donation arrived in 2007 when the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation pledged $10 million for the renovation of the existing Pioneers of Flight gallery, the development of future exhibits, and the creation of early childhood education programs. Barron Hilton, a member of the Foundation’s board and a pilot and enthusiastic supporter of the aviation community, wished to share his life-long love of aviation with visitors of all ages. The new Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight Gallery would be the first gallery to include space dedicated to engaging the Museum’s youngest visitors.

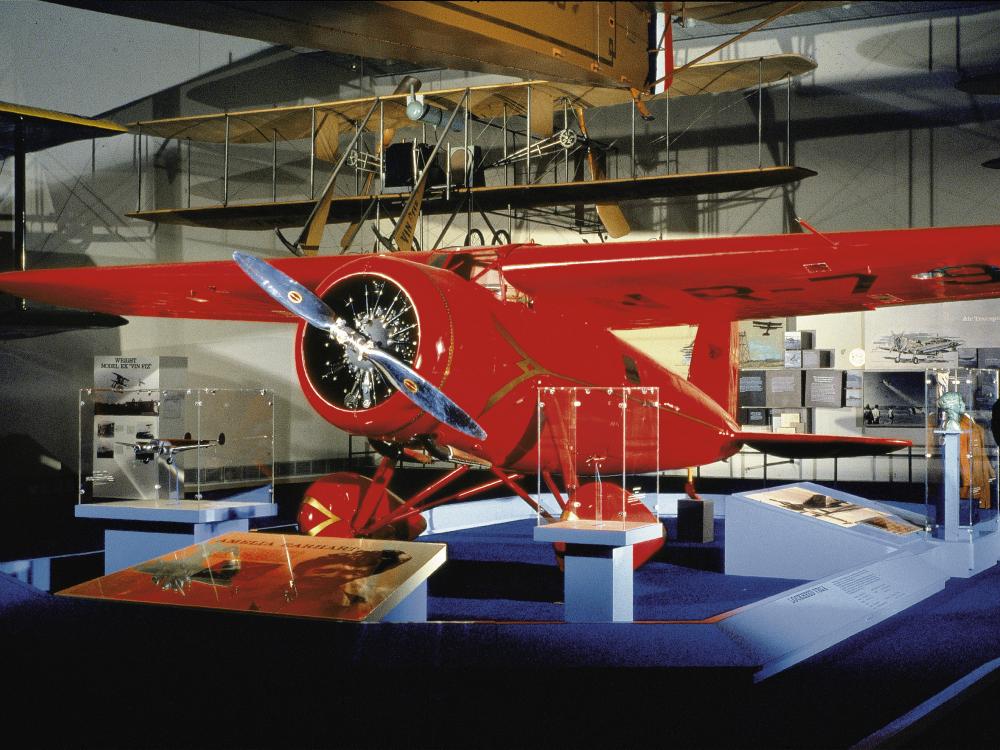

The Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight Gallery at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

When we started our upgrades to the gallery, the overriding question was: How do we make this gallery relevant and inviting to the public? There was no question that the original core aircraft would remain, so the challenge became invigorating each unit and not only documenting each achievement and pioneer but also putting those achievements in perspective with the larger aviation scene and the vibrant era.

First we returned the gallery to its original time frame, the 1920s and 1930s. Then we included much more on the pioneers themselves—Charles and Anne Lindbergh, Jimmy Doolittle, Amelia Earhart, and the others who promoted the growth of public “air-mindedness” through the spectacle of flight. We removed non-period aircraft and added our Piper J-2 Cub to represent grass-roots general aviation envisioned by C.G. Taylor and William Piper. We restricted the Black Wings unit nearly to the stated time period but included more of those seeking racial and gender equality. We provided insight on the relationship of Army and Navy record setting and air racing to interwar military budgets and raced other countries to the stratosphere via balloon. We added the excitement of the wildly popular National Air Races and featured the work of rocket pioneers Robert Goddard and Konstantin Tsiolkovsky with their dreams of spaceflight and rocket experimentation. The original Pioneers of Flight gallery that opened in 1976 was clearly “celebratory.” The 2010 renovation revealed a broader view of military and civilian flight and told the stories of people pushing the boundaries of technology, culture, society, business, and the imagination as aviation advanced from a curiosity to a viable technology.

Now we are embarking on a multi-year project to transform the Musuem inside and out, by updating the exterior cladding and presenting new and redesigned galleries. With a new $10 million gift from Barron Hilton and the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, the Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight Gallery will be transformed with a new design, layout, presentation, and programming, while retaining its basic theme and content, that of the 1920s and ‘30s. With Barron Hilton’s death in September 2019, his lifelong commitment to inspiring the next generation of pilots will live on within the walls of the reimagined gallery.

We can’t wait to share the new gallery with you when it reopens, but here’s a sneak peek: One new aircraft joining the gallery is the curious Mignet HM.14 Pou du Ciel, known as the Flying Flea. The diminutive Flea offers qualities of the Piper Cub’s success, a simple and inexpensive aircraft, in the form of a homebuilt plane for the common man. From the Cub, Flea, and other flivvers came the thriving homebuilt and light sport aircraft communities of today. Other tweaks and surprises to the gallery await in 2022.

In the meantime, we encourage you to explore the online Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight exhibition, which features a lot of in-depth information on the aviation pioneers you know and love and introduces you to even more.

October 23, 1927 - September 19, 2019

Entrepreneur Barron Hilton

Gliders, balloons, helicopters, aerobatic aircraft, and antique biplanes… his passion for flying and his competitive spirit made Barron Hilton a great success in business and a great friend of aviation.

Barron Hilton founded several companies, including the Los Angeles Chargers of the American Football League, before succeeding his father – the legendary hotelier Conrad Hilton – as head of the world famous Hilton Hotels Corporation. During his Navy service during World War II, Hilton took private flying lessons and earned his single-engine license. Then, at age 19, he earned his twin-engine rating at the University of Southern California’s Aeronautical School. He subsequently devoted much of his life to supporting aviation.

For several decades, glider pilots from around the world competed for the Barron Hilton Cup and a unique prize-a weeklong soaring camp at Hilton’s ranch in northern Nevada. Hilton sponsored several efforts to fly nonstop around the world in a balloon. He was a longtime supporter of the Experimental Aircraft Association’s Young Eagles Program which encourages aircraft owners to give rides to youngsters to introduce them to the joy of flying.

The Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight Gallery at the National Air and Space Museum is generously sponsored by Barron Hilton and the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation with the hope that future generations of young people let their own dreams soar to new heights.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.