The Daily Life of the Tuskegee Airmen: The Lieutenant Rayner Collection

Feb 22, 2022

By Elizabeth Borja

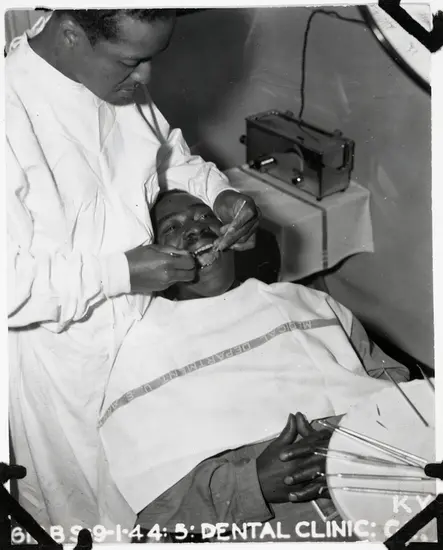

In 1982, the National Air and Space Museum opened the exhibit Black Wings: The American Black in Aviation and the companion book was published the next year. The exhibit relied heavily on donations of historical photographs, including a set of black and white copy US Army Air Force photographic negatives donated by Ahmed A. “Sammy” Rayner, Jr. These images, paired with Rayner’s remembrances of his time as a Tuskegee Airman, provide vivid examples of the daily lives of the 477th Bombardment Group and their training activities in the United States. His experiences as a Black officer and pilot later fueled his postwar political activity.

Ahmed Arabia “Sammy” Rayner, Jr. was born in Chicago in 1918. His father, Ahmed Sr., was a mortician with degrees from Prairie View A&M University, Worsham College of Mortuary Science, and, later, John Marshall Law School. Rayner led an active life in high school as a member of the track team, ice skating team, and served as president of the Sign Painters Club and treasurer of the Civil Industrial Club. He started his college career at the University of Illinois, but his father persuaded him to study at Prairie View, his alma mater. Rayner was just as busy in college as a member of the tennis team, drama club, intramural football, cheerleader, and president of the sophomore class. He graduated in 1939 with a B.A. in history and a minor in government, his undergraduate thesis titled, “A Comparative Study of the Characters and Administration of the Two Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Roosevelt.”

Rayner also followed his father into the mortuary business graduating from the School of Embalming at the University of Minnesota. In 1941, he was inducted into the Army. He went to Basic Training at Camp Davis and then attended Officers Candidate School, receiving his commission in August 1942.

In a 1985 oral history group interview with Studs Terkel, Rayner recalled his first trip to Tuskegee, Alabama, where Black officers and enlisted men were to receive the opportunity to learn to fly. He had been stationed at Fort Brady in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, guarding the border. He went by train with several other Black men. He had been south before and had heard of previous arrivals’ rough experiences, particularly at the train station, so he steeled himself to exit the train, prepared to let the situation determine his reactions. However, there was a taxi waiting to take them straight to Tuskegee.

Rayner received his wings in March 1944 and married Geraldine Chambers a few days later in Cairo, Illinois. He then received B-25 flight training at Mather Field in California. In May 1944, he joined the 616th Bombardment Squadron at Godman Field, Kentucky (located at Fort Knox). The squadron was part of the 477th Bombardment Group, the first and only bombardment group with Black aviators. Rayner recalled life in the squadron, which never went overseas, in a segregated military: “They didn’t know what to do with us. We trained and trained. Every time we looked up the radio operator, tail gunner would be going away to school somewhere. And we never really got the complete togetherness that we were supposed to have until [Black pilots] came back from overseas.”[i]

Rayner was promoted to first lieutenant in January 1945. As part of the 616th Bombardment Squadron, he was stationed at Freeman Field, Indiana, during the April 1945 “Freeman Field Mutiny,” in which Black officers attempted to enter a segregated officers club. Rayner was not part of the officers' group. “I was living off the base. I was married…and I had a little apartment there at Freeman Field and I didn’t know anything about this. I got in the next morning and I hear they’ve got these guys lined up getting on a C-47 going back to Godman.

“But it was…the most dehumanizing thing I’d ever seen. Here are these men—all of them men with knowledge, learned men, men who were flying, doing a good job training, and here they were in chains just like dogs. I never shall forget that.” Rayner highlighted future Detroit mayor Coleman Young’s role in the act of civil disobedience, “Coleman Young, a firebrand, was the leader and he’s been firebranding ever since.”

After World War II, Rayner returned to Chicago and the mortuary business. Together his family opened A.A. Rayner & Sons Funeral Home in 1947. In 1955, Mamie Till brought the body of her murdered son, Emmett Till, to A.A. Rayner & Sons, insisting upon an open casket so that all could see what had been done to him. More than 50,000 people mourned, with lines stretching around the block.[ii]

Rayner’s experiences during World War II informed his active participation in the Black community and politics in Chicago. He was the treasurer of Protest at the Polls, a group of young civil rights activists (dubbed militant in some newspaper articles), when he first ran for political office in 1963. The next year, he campaigned and lost on a “strong civil rights” platform for the Democratic nomination for the House of Representative, earning the support of James Meredith, who had desegregated the University of Mississippi. Rayner successfully became the Alderman for the 6th Ward of Chicago, serving until 1971. He ran for Congress again in 1975 and for mayor in 1977. Rayner was also an outspoken critic of the Vietnam War, with quite the FBI file as they explored his relationship with the Black Panther party.

Rayner looked back on his time as a Tuskegee Airman with pride. He was an active member of the Chicago Officers Council, established by members of the 477th Bombardment Group, later nicknamed the Dodo Club, since “through atrophy they had lost the ability to fly.” They celebrated the accomplishments of their alumni, sending a letter of congratulations in 1955 to Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. when he was temporarily promoted to Brigadier General (made permanent in 1960). He summed up his experiences: “I got an opportunity to fly, something I’ve always wanted to do…[and] to meet some fine people. I’ll never forget some of them. I’d like to tell that I played a part on making these United States a better place to live for everybody.”

[i] All direct quotes from Rayner are from the 1985 oral history group interview with Studs Terkel.

[ii] A.A. Rayner & Sons has moved and is now located on the part of 71st St. renamed “Emmett Till Road” in 1984.

Related Topics

You may also like

Related Objects

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.