On January 25, 1925, J.H. Klein Jr., the commander of the airship USS Los Angeles, described an incredible sight he had witnessed to the Boston Globe. He described his experience and stated it was, "A most spectacular sight. The sky at the horizon was a flood of merging orange and red light. Overhead the ceiling was blue-black, while all about was the darkness of twilight.” This incredible event occurred during the 1925 solar eclipse off the coast of New York City, and scientists and crew aboard the USS Los Angeles had a front row seat to the beauty and splendor of the occurrence.

The USS Los Angeles, also known as ZR-3, was a rigid airship that started its career as LZ-126. The airship was built by the Zeppelin Company in Friedrichshafen, Germany, as compensation for two airships destroyed in 1919 that had been intended for the U.S. military. As a result of conditions set within the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was unable to build any military craft, so LZ-126 was constructed for civil purposes. The interior featured luxury seating for passengers, as opposed to a pure military functionality. The actual construction began in June 1922, and the first flight was in August 1924. It underwent several months of test flights before it was finally flown across the Atlantic in October 1924 and officially transferred to the U.S. Navy. Once the airship was officially made a part of the fleet, it was used to train U.S. lighter-than-air crews, as well as experiment with new technologies and techniques, such as mooring to different types of masts. The solar eclipse of 1925 provided another opportunity for the USS Los Angeles to showcase its usefulness for scientific purposes.

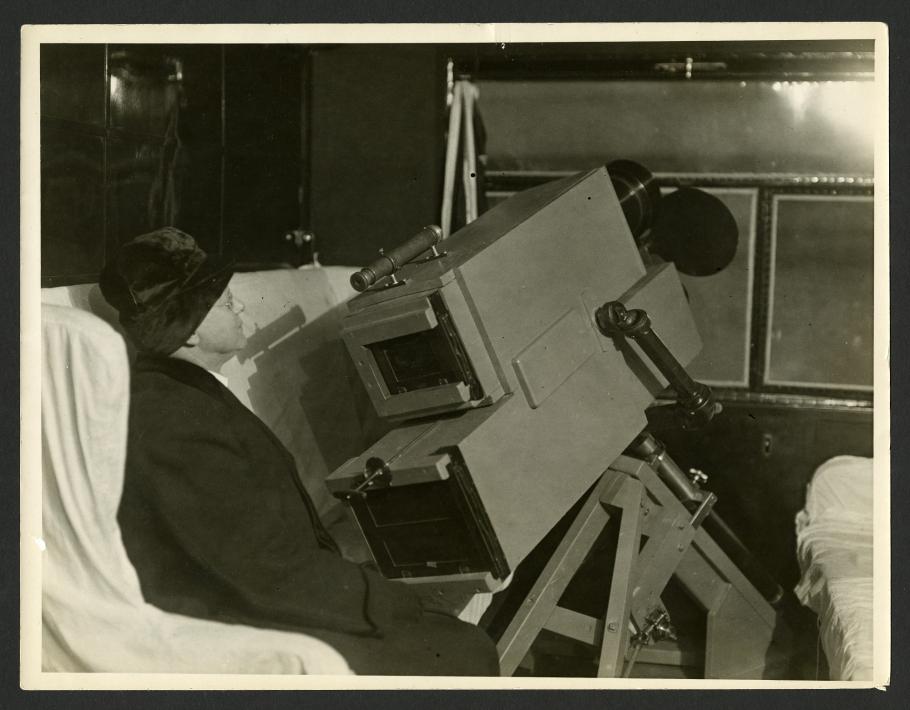

January 1925 marked the first time in over 100 years that a solar eclipse was going to be visible over the United States. Excitement built throughout the country as the time neared for the eclipse to occur, and many proposed that aircraft could allow for better photography of the eclipse than ever before. The USS Los Angeles was stationed in Lakehurst, New Jersey, at the time and provided an excellent opportunity for the Navy to showcase the utility of the rigid airships. Scientists from the U.S. Naval Observatory prepared for the flight and procured special cameras that could be used aboard the airship during the flight to record the eclipse from high up in the atmosphere.

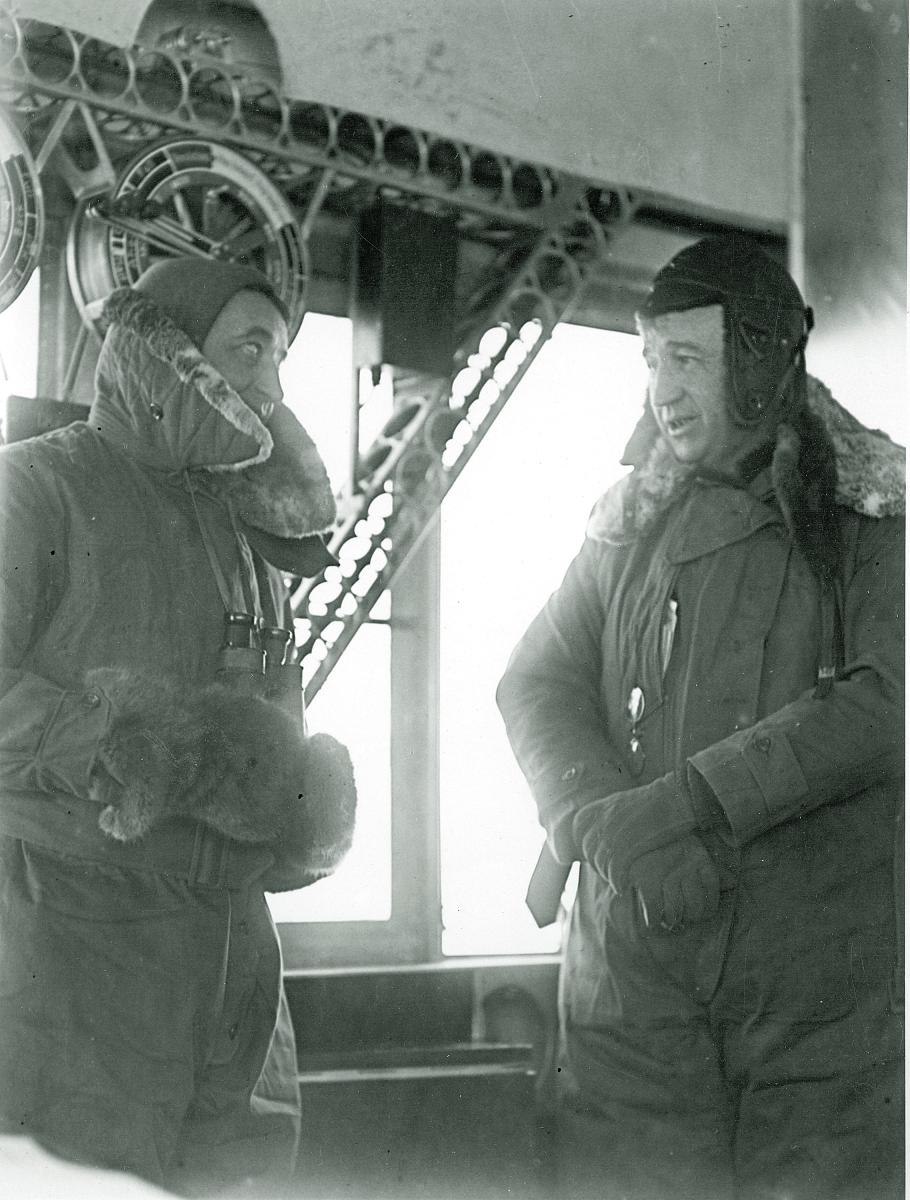

In the bitterly cold early morning hours of January 24, 1925, the scientists and crew of the USS Los Angeles loaded up the equipment and cameras and took to the sky off the coast of Long Island, New York, after facing numerous days of strong winds that had kept them grounded. The USS Los Angeles rose to an altitude of over 4,000 feet, giving those on board an unparalleled view of the sky around them. The control car was unheated during the flight, and all those aboard had to dress warmly to cope with the cold temperatures. Along with the special cameras, scientific instruments such as spectrographs were prepared so numerous readings could be taken as the eclipse approached totality.

Watson Davis, assistant editor of the Science Service news service, had been invited to accompany the crew and scientists aboard the Los Angeles, and reported his observations over the radio during the flight. The New York Times, on January 25, 1925, reported his description of totality: “"Lifted a mile closer to the sun by the navy dirigible Los Angeles, the United States Naval Observatory Astronomers had a perfect view of the total solar eclipse. During the two minutes, four and six-tenths seconds of totality, not a cloud marred the magnificent spectacle of a sun so completely blotted out by the moon that the coronal fringe of the light and the ghostly radiance of the eclipsed sun turned the ocean horizon and the clouds below into a vivid picture in yellows, purples, and grays."

Cameras clicked and measurements were rapidly recorded as scientists attempted to record as much data as possible during the short timeframe of totality. Many of those aboard the USS Los Angeles, however, did take a moment to pause and take in the splendor of the eclipse seen in a manner few have ever experienced. Alvin K. Peterson, chief photographer of the U.S. Navy, told the New York Times that, “The intense cold gripped him… at the same moment the eclipse blotted out his view of the earth. He described it as 'the weirdest sensation I have experienced.’”

Following the eclipse, many of the scientists were thrilled with the data they were able to gather. Some of the images and film did suffer because of the engine vibrations of the USS Los Angeles, but much data was successfully collected. The Washington Post reported, “Scientists felt justified in declaring that a huge fund of information undoubtedly had been added to their store of general and specific knowledge about such mysteries as the content of the sun's corona, the composition of eclipse umbra and penumbra, the explanation of the 'jumping jack rabbit’ of the moon's eclipse shadow, the deflection of light as related to the Einstein theory, the effect of eclipses upon Earth's climate and tides and gravity and its effect upon radio activity, upon Earth's magnetic centers, its thermometers and its barometers."

The data collection, however, was not without risk. The Boston Globe reported, “A.E. Peterson of the Bureau of Aeronautics was the only member of the expedition to suffer personal injury. In the intense cold his nose and the left side of his face were frozen. Despite the cold, he stuck to his exposed position on top of the ship from 7:45 until 10:30, turning the crank of his special long-range motion picture camera."

April 8, 2024, marks another opportunity for many in the United States to witness a solar eclipse. Although you may not enjoy such a prime spot as aboard a rigid airship at 4,500 feet, we hope you take the time to pause and look up at the eclipse and observe the incredible moment that the shadow crosses the Sun (through approved solar eclipse glasses.) It is a rare opportunity when we can observe an event that has excited people for hundreds of years, and one that people strive to record even to this day.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.