Capt. Bob Snowden

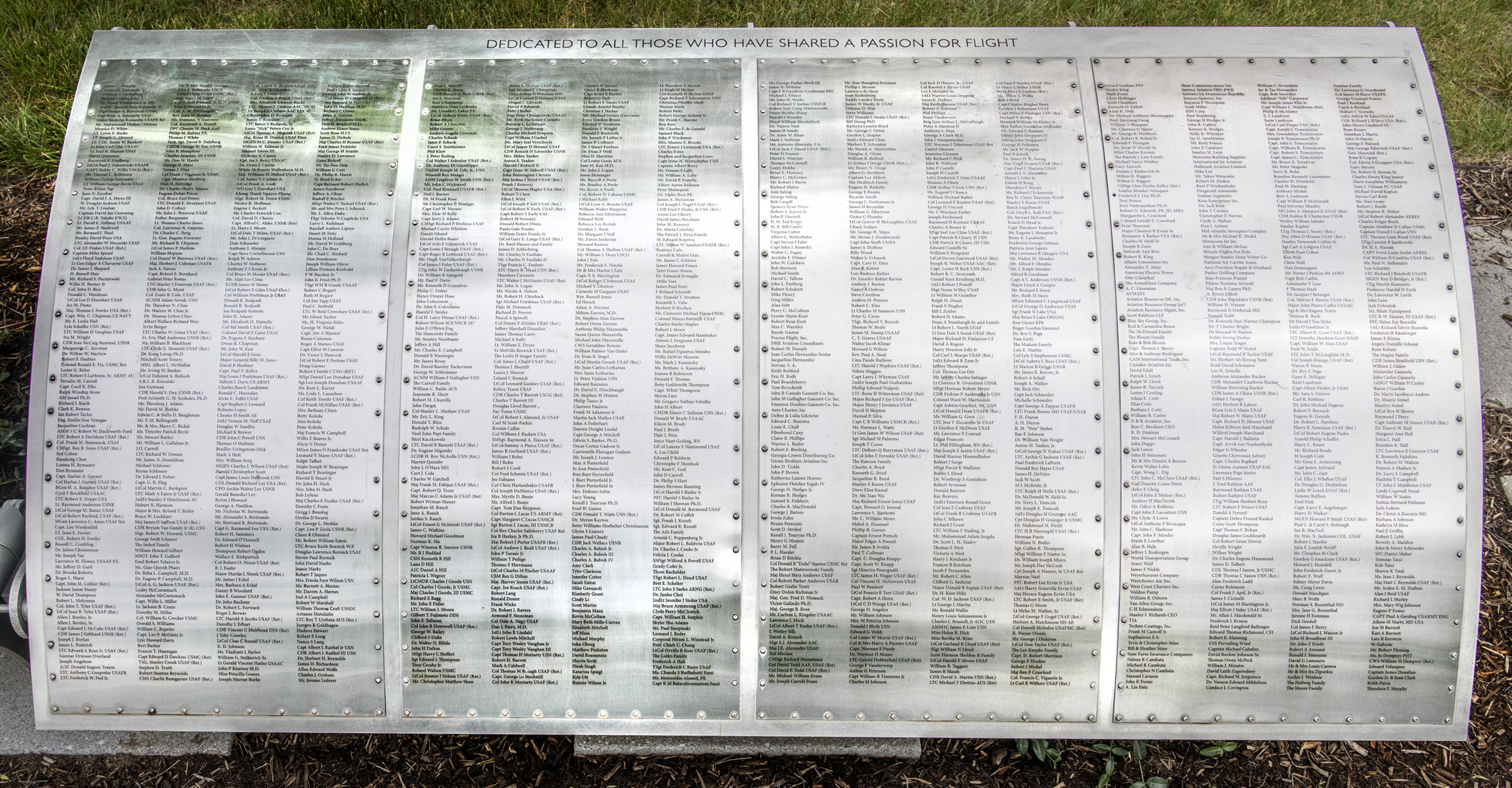

Foil: 5 Panel: 4 Column: 3 Line: 3

Wall of Honor Level: Air and Space Friend

Honored by:

I have been involved in aviation since 1928 when I had my first instruction in an OX-5 Swallow at Curtiss Field, Long Island, NY. I have flown from Jennies to jets for 72 years with 4 years in the US Navy (1942-1946) and 27 years years with Seaboard World Airlines and Flying Tiger Airlines, retiring from the airlines in 1973 with almost 30,000 flight hours.

Still flying under the banner of UFOs (United Flying Octogenarians). How lucky can one get?!

The following is extracted from an article in "The Suffolk Times," 19 December 2002.

An airline pilot has a glamorous job, right? Flying high in the sky, commander of his plane, meeting daily challenges, wearing that snappy uniform.

Not exactly, says Captain Bob Snowden of Cutchogue, a veteran of 72 years of flying every kind of plane you can name. A more accurate description of life aloft, he says, would be "Hours of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror."

Like the moment he was flying 98 passengers on a four-engine triple-tail Constellation in 1960 from Tokyo to Wake Island, then on to Honolulu and San Francisco. They were beyond the point of no return when one engine quit. Capt. Snowden radioed for help and the Sea Air Rescue service sent a plane to intercept the Constellation in case it had to land in water. Stewardesses helped passengers into life vests called Mae Wests and tried to keep everybody calm. The rescue plane flew alongside them until they were about two hours off Wake. Then the rescuers had a problem themselves. An engine had quit. They had to fall back.

"We kept flying on three engines," Bob recalls. "Then another half hour and another engine quit. We were losing altitude, it was scary. Well, we managed to slide in on a wing and a prayer into Wake." He shook his head, "It was a moment of terror."

Another moment of terror occurred when his plane, a Douglas DC-4, came within a hair's breadth of a mid-air collision over Germany. He was flying displaced persons from Munich to the United States at the end of World War II. Bob had left the co-pilot to go to the rear of the plane for a minute when suddenly the plane rocked violently. He ran back to the cockpit in time to see exhaust gases spray across the windshield. A military jet fighter out of Wiesbaden had come within feet of smashing into their DC-4. "I was shaking, believe me," he said. Otherwise, Cap'n Bob (as he's called around Cutchogue) said piloting a plane around the world becomes routine.

Now about to celebrate his 89th birthday on Christmas Day, Robert E. Snowden Jr. can remember the thrill of watching early "barnstormers" do aerial stunts at Roosevelt Field, the same field from which Charles Lindbergh took off to make his historic nonstop flight across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927. Young Bob wasn't at the field that morning. His mother insisted 14-year-old boys belonged in school.

But the boy was still determined to become a pilot. He sold programs for the air shows and cleaned out the barns for the fliers. By age 15 he was flying one of the first double-winged biplanes, a Swallow with a Curtis engine. At 16 he had his pilot's license.

His mother feared that he would become just another mechanic, a "grease monkey." She directed his attention toward college and a degree in aeronautical engineering. Then, when a family friend, an executive with Brooklyn Union Gas Co., suggested he might have a job with the company, she persuaded young Bob to switch his major to mechanical engineering. A job in those Depression days was a powerful motivator. He switched and got the job, staying with the gas company about five years while continuing flying lessons whenever he could.

By this time he had met and wooed one of the most popular girls in Garden City, Marjorie Burkhard, who worked in a New York City bank. They were married in 1938.

With the outbreak of war, Bob was given a commission in the Navy and assigned to teach flying. Later he advanced to the Naval Air Transport Service. This was his education in airline flying, he says.

Besides a daughter in Muttontown and a son in Los Angeles they have three grandchildren and five greatgrandchildren.

Bob's den contains mementos of a lifetime of flying and collecting antique cars. Besides models of the 35 or 40 different planes he's flown over the years he has models of the 15 or so antique cars he has owned and driven over a lifetime.

Mounted in a glass case on the wall are several sets of wings: one from his first flight instructor, a World War I pilot, one from the Navy and others from various airlines for which he flew: Seaboard and Western, Seaboard World and Luxembourg, once partially owned by Seaboard World.

Over the years he's helped make aviation history. Besides having flown thousands of times across the Atlantic, he participated in the Berlin Air Lift in 1948 and 1949, bringing food, coal and other supplies to the beleaguered people of Berlin under Soviet blockade. Later he flew in the Dewline early warning system that the United States set up around the Arctic Circle to protect against a possible Russian missile assault during the Cold War. At one time he was president of Seaboard Pilots Association Retirees and later organized the Early Fliers Club.

In anticipation of retiring from Seaboard World in 1973, while he was still flying Pacific routes, he and Marge bought a home near Napa Valley. But California turned out to be too far from Long Island and friends. "Marge looked so sad at breakfast each morning that I finally said, why not go home and find a place you like," Bob recalled.

Back in Cutchogue he started instructing at Mattituck Airport, a post he kept for nearly 30 years. "I like to keep busy," he said — a major understatement. At one point he and four pilot friends bought an 18-acre marina in Westbrook, Conn., for $75,000, which they sold 10 years later for $1 million. About this time he opened an agency to sell sailboats. He also was tennis chairman for the North Fork Country Club for at least 10 years.

Painful arthritis in his hands has made sailing and driving his beloved cars too difficult in recent years. He gave up his 25-fobt sloop and sold the last of the cars, contenting himself with the models in his den.

Is there anything he still wants to do? I asked the practically 89-year-old. "Live to be 90," he laughed.

Wall of Honor profiles are provided by the honoree or the donor who added their name to the Wall of Honor. The Museum cannot validate all facts contained in the profiles.

Foil: 5

All foil images coming soon.View other foils on our Wall of Honor Flickr Gallery