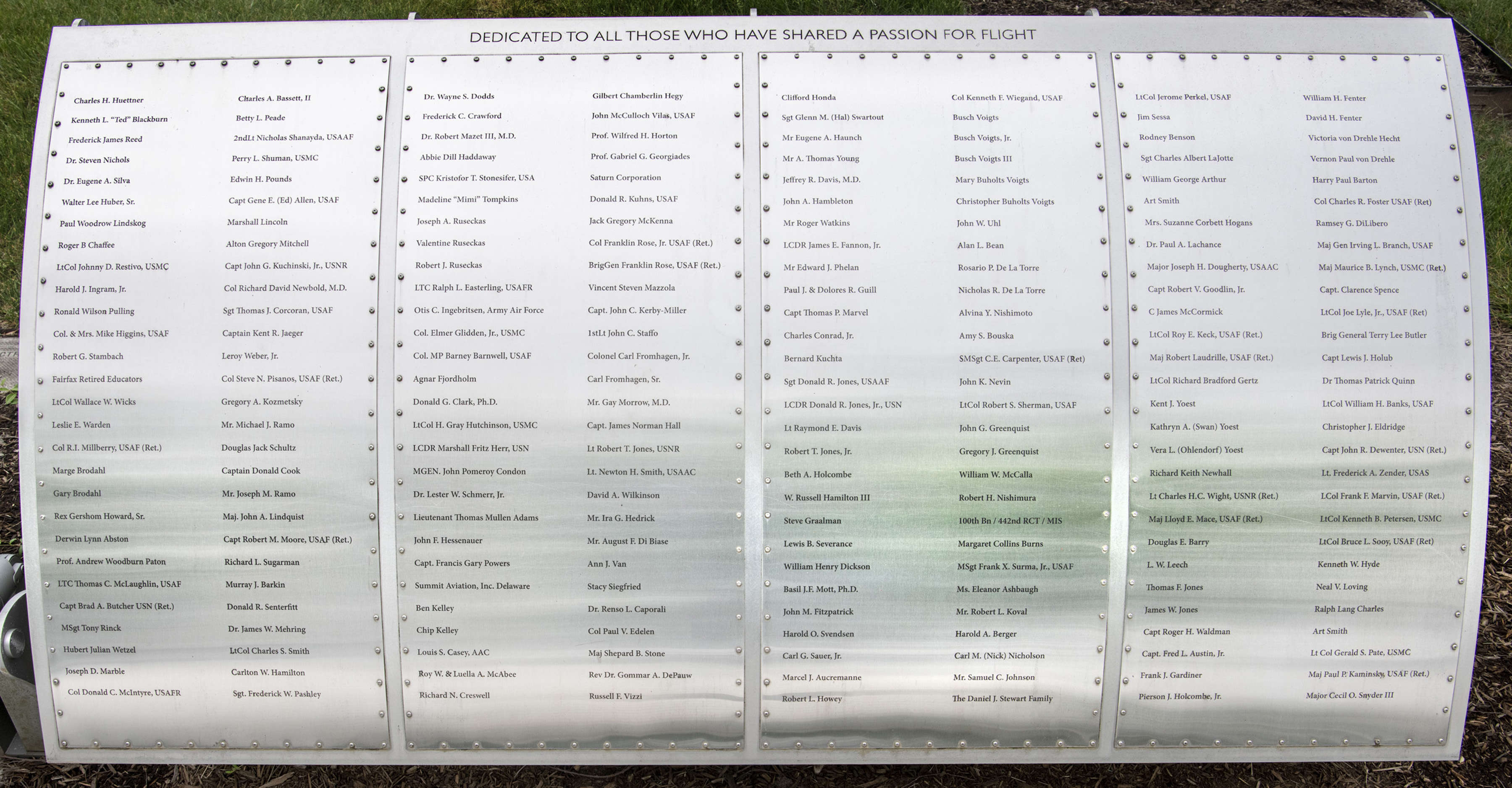

Frank J. Gardiner

Foil: 24 Panel: 4 Column: 1 Line: 27

Wall of Honor Level: Air and Space Sponsor

Honored by:

The Lunar Module (LM) was one of the critical engineering challenges of the Apollo program. Although the Apollo program itself dates back to the 1950s, the concept of lunar-orbit rendezvous was not even contemplated until 1961.

Until that point, our space program was geared toward going to the moon by means of an earth-orbit rendezvous technique. This would have involved launching the payload of two Saturn rockets, uniting them in earth orbit and sending one giant spacecraft to the surface of the moon.1

In 1961, Dr. John Houbolt, Chief of Theoretical Mechanics at NASA's Langley Research Laboratories, was advocating that the space agency give serious consideration to his lunar-orbit rendezvous idea, as being more reliable and faster to design and build.

The idea looked good on paper, and one evening I sat down with Dr. Leslie Matson, then my close associate at RCA, and we computed the trajectories and weight requirements for lunar-orbit rendezvous. Immediately, we saw that this technique was clearly superior to earth-orbit rendezvous, both in terms of reliability and the time required to build a spacecraft capable of landing a man on the moon.2

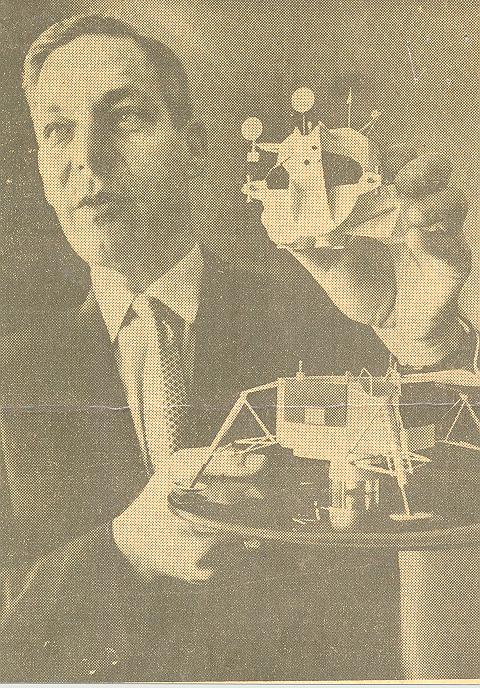

In January 1962, RCA and Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation joined forces, on an unsolicited basis, to make a study of the superiority of the lunar-orbit rendezvous for submission to NASA. Mr. Gardiner led the study for RCA, working with Joseph Gavin and Thomas Kelly of Grumman and their team.3 In the six-month period between February and July 1962, RCA & Grumman made a complete design of the LM and its mission.

After we submitted our study, complete with the LM design, a heated debate took place between the backers of the earth-orbit technique and those of us who supported the lunar-orbit route. At that time, the mainstream of thinking favored the former, largely because of inertia. Millions of dollars already had been earmarked for earth-orbit rendezvous vehicles, and schedules had been laid out. To change direction at that point seemed like a monumental waste. All the design work that had been completed on the Command Module (CM), for example, would have to be changed radically in order to accommodate a connection to the LM at the tip of the cone.4

In July 1962, NASA officially announced its preference for lunar-orbit rendezvous over earth-orbit rendezvous.

By the end of July 1962, NASA had issued invitations for bids on the construction of the LM. We teamed with Grumman for this implementation phase and submitted our proposal in late August. The following month, we received word that Grumman would be named prime contractor and RCA would design and build much of the electronic subsystem. During October, November and even into December, we were almost constantly down in Houston attempting to finalize our role in the program and in refining some features of the design that we had originally submitted in accordance with NASA's evaluations and requests.5

After Apollo 11 successfully landed men on the moon, Mr. Gardiner said of the debate over earth-orbit rendezvous and lunar-orbit rendezvous:

The flight of the Apollo 11 bears out my conviction that the people who had the courage to make that decision did the right thing. I have no doubt that had we gone in the direction that was originally contemplated, we would still be talking about manned lunar landing in the future tense. And the entire Apollo program would have been much more costly because of the great problems involved in landing a huge CM on the surface of the moon. For instance, the last minute maneuver made by LM commander Neil Armstrong to avoid landing in a rough crater would have been much more difficult to perform in a weighty CM with limited ground visibility. It would have been like piloting a 747 jumbo jet instead of a helicopter.6

After NASA awarded the contract around Christmas 1962, Mr. Gardiner moved with the LM Program Office to RCA's Aerospace Systems Division (Burlington, Massachusetts) as LM Program Manager. The RCA-LM program started in Moorestown, New Jersey in the Major Systems Division

on January 31, 1963. RCA's responsibilities on the LM project were for the radar (which measured the distances and velocities of the LM relative to the moon and relative to the CM), communications, in-flight test and ground checkout subsystems as well as for stabilization and control electronics.

Mr. Gardiner was born in Vienna, Austria in 1923. Following studies at the English Preparatory School in Switzerland, Mr. Gardiner studied mathematics and physics at the Harrow School in England where he received the Oxford and Cambridge Higher National Certificate in 1940. In 1943, he received his BS degree in Aero-Thermodynamics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After graduation, Mr. Gardiner was employed by the Chrysler Corporation. He then served 18 months in the United States Navy, Pacific Fleet, before being commissioned and named officer in charge of Turbine and Compressor Development for the Bureau of Aeronautics, where his work included study of German rocket development.

In 1947, Mr. Gardiner became Chief Engineer of Special Products Division, ITE Circuit Breaker, Philadelphia; principal products were microwave antennas and devices for both radar and communication systems. As a result of the growth of the Engineering Department, a separate division was set up in 1955 to design, test, market, and produce these devices. Mr. Gardiner managed that operation.

Mr. Gardiner joined RCA, Major Systems Division, Engineering Department in 1961. He became manager of the Tactical and Space Systems Programs in 1966 and Manager of Systems Development and Applications in 1969.

Mr. Gardiner left RCA in 1971 to work with Laser Credit Control to develop a credit card verification system. In 1975, he joined Honeycomb Roll Systems, Inc. of Saco, Maine as Technical Director where he developed measurement devices and control instrumentation for the paper industry.

Mr. Gardiner was awarded numerous patents, including 17 in his own name, for a wide variety of technical developments. Mr. Gardiner was killed in an automobile accident in January, 1979.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 Interview with Frank J. Gardiner, RCA Electronic Age, Autumn, 1969, p. 22.

2 Interview with Frank J. Gardiner, RCA Electronic Age, Autumn, 1969, p. 22.

3 Moon Lander, Thomas J. Kelly (Smithsonian Institution Press), p. 24.

4 Interview with Frank J. Gardiner, RCA Electronic Age, Autumn, 1969, p. 23.

5 Interview with Frank J. Gardiner, RCA Electronic Age, Autumn, 1969, p. 23.

6 Interview with Frank J. Gardiner, RCA Electronic Age, Autumn, 1969, p. 23.

Wall of Honor profiles are provided by the honoree or the donor who added their name to the Wall of Honor. The Museum cannot validate all facts contained in the profiles.

Foil: 24

All foil images coming soon.View other foils on our Wall of Honor Flickr Gallery