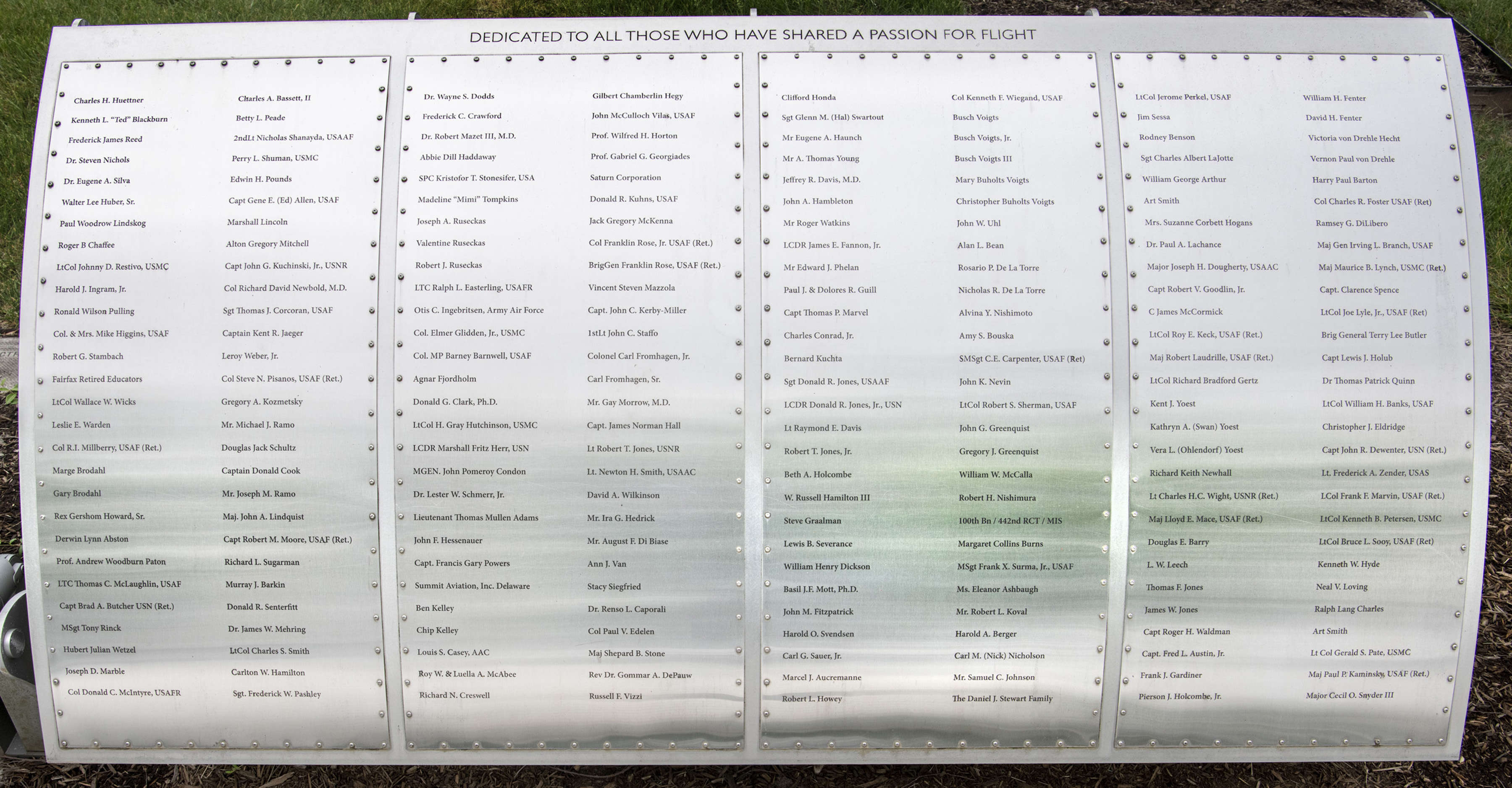

Foil: 24 Panel: 1 Column: 1 Line: 26

Wall of Honor Level: Air and Space Sponsor

Honored by:

Ms. Doreen B. Wetzle

Born on October 1, 1922, Hubert Julian Wetzel was the third child of a farming family near Alhambra Illinois, about 30 miles northeast of St. Louis, Missouri. Growing up less than a mile from the center of town (300 people) located on the Illinois Central and Nickel Plate Railroads, Hubert enjoyed both "city" and "country" childhood experiences. Those included the opportunities available in school, church, Boy Scouts, and the local 4-H Club. All school sports and scouting adventures provided a good opportunity for physical and motor skill development. Interested and caring teachers, in a small class environment, challenged each student to strive for excellence in achievement. An outstanding progressive school administrator provided the leadership to have choir, orchestra, and band available to grade and high school students. Mr. C. A. Stickler had a great impact on the 100 plus students during each of his eight years at Alhambra Grade and High School. He constantly challenged students to set the 4-H motto, "MAKE THE BEST BETTER," as their goal.

Interest in aviation developed early for Hubert. His sister Onita used to say, "Maybe that's Lindy" in one of the planes flying over our house, either west to St. Louis, or east to New York. Our farm at Alhambra was very close to the beacon-light system, with the closest beacon at Kaufman Station just several miles to the southwest. Located every ten miles, the one at Kaufman Station was 20 miles east of the Mississippi River at St. Louis. The St. Louis Airport, Lambert Field, was about 10 miles west of the river on the west side of the city. Charles A. Lindbergh's search for funding to build a plane and become the first person to fly solo from New York to Paris was answered by the citizens of St. Louis, who gave funds to build the plane and finance the trip. Lindy and his plane, named "THE SPIRIT OF ST. LOUIS," made history during a grueling 33 1/2 hour flight on May 20-21, 1927 - covering a distance of 3,600 miles. Lindy was a big hero to five-year-old Hubert, who often imitated him with arms stretched out like wings and making the noise of an airplane engine.

Chauncy Rockwell also stimulated Hubert's interest in flying as he experimented with a 'copter kit about 1930. He lived at Rockwell's Corner, just three miles from Hubert's home. It was a novel attraction but never proved very successful, due to the fact that it had not been designed to travel fast in a forward movement.

Hubert enrolled in the College of Agriculture at the University of Illinois in September 1940. He worked an hour at lunch and two hours at dinnertime for his meals, for Mr. Morris who owned a Greek restaurant on Wright St., near Green Street. Most every Saturday and Sunday Hubert worked extra hours at the going rate of 25 cents an hour for student help. He roomed with Jim Beard, an electrical engineering sophomore, in the Casebier family home, 206 E. John, for $12 a month. U. of I. tuition was $35 a semester.

At the end of the second semester, he found out that his best friend Lee Stickler, a year younger than Hubert, had decided to work a year at Owens Illinois Glass Co. in Alton, Illinois before starting college. The idea of working and saving money to be completely self-supporting was appealing to Hubert, so a job interview followed, resulting in being hired as an assistant inspector responsible for production on two very large bottle machines. Earning 75 cents an hour, plus a bonus of five to ten cents an hour, he worked that summer and decided to work another year, as Lee was doing. Often, he would work a double shift and was paid time and a half for the second eight-hour shift. His Swiss "work-save" ethic

2

built up a tidy savings account for future use and enabled him to "pay-his-own-way" ever since. He was at work when the frightful news of the December 7th Pearl Harbor attack was broadcast over the glass-factory PA system

In September 1942, Hubert enrolled as a sophomore at the U of I, hoping to complete another semester or two before going into service. Uncle Sam cooperated by establishing the ASTP (a college program to encourage students to be better prepared to fill various army technical positions). To take advantage of this opportunity, Hubert signed up in November. After completing his second year of college, he was called to active duty on July 20, 1943, at Camp Grant, Rockford, Illinois.

A series of tests were given the next few days. Hubert received a "9" (highest) rating in the Air Corps battery of tests. He accepted the invitation to pursue the navigator training program. The trail of training took him to Truax Field, Madison, Wisconsin, and Miami Beach, Florida for basic training. The three month college training detachment was at Southwest Missouri State Teachers College, Springfield. After a brief stay at San Antonio, pre-navigation was at Ellington Field, Houston. Then it was off to Laredo for gunnery training in B-24's. Still deep in the heart of Texas, the last phase to obtaining his navigator wings was Navigation School at San Marcos. Hubert graduated in class 44-43 (so designated because the last week in October was the 43rd week in the year 1944) as a commissioned flight officer.

Flying as a crew came next. A one-week furlough was followed by six weeks of concentrated flying with the new crew, at Bergstrom Field, Austin, Texas. On December 22, the crew reported to Baer Field, Ft. Wayne, Indiana. The crew, ready to get their plane and destination, had real concerns when the pilot received a Red Cross telegram that there was a serious family illness. With overnight expediency, a new pilot was assigned to the crew. On December 29, with a new pilot and a new C-47, the crew departed for West Palm Beach, Florida, only to be forced down in Dyersburg, Tennessee in a blinding blizzard. Their first flight almost ended in disaster. Luckily, Hubert spotted a tree faintly, in the snow, as the landing strip was approached and yelled to Pilot Simmons, "TREE veer RIGHT." He did, or the plane and tree might have tangled. In addition to Pilot Edward Simmons, the crew included Co-Pilot Robert Robbins, Navigator Hubert Wetzel, Crew Chief John Miller, and Radio Operator Cleive Sims.

Five days later the weather cleared, allowing the new plane and crew to continue on to Florida. A one day delay, so that radio equipment could be repaired, gave the crew its opportunity to have a little fun. The crew of five, including pilot, co-pilot, navigator (Hubert Wetzel), crew chief (mechanic), and radio operator engaged a boat-owner-captain to take the crew fishing in the Atlantic. For eight dollars each, the crew learned to deep-sea fish in about five hours. They did catch some, which were given to the captain as a tip. No smelly fish allowed in the plane!

The next day, with radio working, the crew flew to San Juan, Puerto Rico and over-nighted. The next stop was Georgetown, British Guyana. When the crew arrived the following day in Belem, Brazil, it learned that the next day would be spent flying a search mission over the jungles. A couple of planes had been lost in the past two days, so the crew was assigned an area to fly 60-mile legs back and forth, every 2 1/2 miles, at an altitude of 1,000 feet. This might have been too far apart, because no aircraft wreckage materials were spotted - only one old, weathered raft that could have been a bright yellow dingy much earlier. That was reported to the Air Corps Command at Belem.

The next flight was to Natal on the northeast comer of Brazil. Ascension Island was the destination on Day 6 away from the North American Continent. Two hours out, the radio failed, so the plane returned to Recife, Brazil, located on the coast, south of Natal. While the crew slept, radio technicians doctored the electronic equipment so the second attempt to find that tiny island in the South Atlantic was successfully completed.

Pilot Simmons heeded the warning to come in low and slow to Ascension Island. The main landing strip had a hump in the middle. Touching down toward the middle could cause the plane to be airborne again a few seconds later. The rock was so hard that the construction crews never quite got the landing strip flat. It sure made pilots alert when they were briefed at the previous bases, headed to Ascension Island. As the plane approached the high area of the runway, it was very noticeable. All 34 square miles (smaller than the normal 6x6 square mile Illinois townships) were very rugged, so it was difficult to build an airport landing strip. The crews' second encounter with the Atlantic Ocean came after supper, when they headed for a refreshing dip in the ocean. The first dip in the ocean was from the deep-sea fishing boat in colder water the week before, off Ft. Lauderdale.

A very northerly flight the next day ended at Freetown, Sierra Leone, on the south receding edge of the great African bulge. That night the crew learned the importance of netting in mosquito country. Just a few degrees north of the equator with humid temperatures several degrees over a hundred, the crew wished the Dyersburg, Tennessee blizzard would blow in long enough to freeze the hordes of mosquitoes. All efforts were made to make sure the mosquito netting surrounding the army cots had no cracks or tears.

One of the shortest legs of the Ft. Wayne, Indiana to Norwich, England trip was the one from Freetown, Sierra Leone to Dakar, Senegal - about 500 miles, on January 12 -Day 9. Day 10 was the bleakest flight of all, as much of it was over the Spanish Sahara Desert to Marrakech, Morocco. It was at the mess hall that evening that the Moroccan table waiters proved their skill. Replenishing our coffee cups, the waiters would pour coffee, two at a-time, a pot in each hand. Those waiters would probably become good pilots with a little stick time!

Day 11 was one of the longest and most vividly remembered of the 12 day journey from the USA to Norwich. Up at 4 A.M., the crew flew from Marrakech to Port Lyautey on the coast north of Casablanca. There, we had the gas tanks and the four 275-gallon temporary storage tanks, mounted in the cabin, completely filled so the planes two 1250-horsepower engines would have enough fuel to make the gigantic leap from Africa to England. Heading out to sea, the course was all over water because Spain was to be avoided. Spain was not friendly to the Allies at that time. Exceedingly turbulent weather, both up high and down low, gave the plane and crew the feeling like they were riding a bucking horse in a rodeo. Some 14 hours later, with gas gauges showing about 20 minutes of fuel remaining, the airfield at St. Agnes near Lands End, England greeted our relieved eyes and minds. The plane touched down at 8:15 PM - three hours after '01 Sol had turned in for the night. Though warm inside, and the fact that the crew had survived a most difficult flight, they had a very cold night in the unheated barracks. Only the rough wool English Army blankets reminded the crew that they would survive a second close call at the end of the mission - freezing to death.

The 12th day, January 15, with a good, hot English Army breakfast, the crew took their new, but well tested plane for its last flight easterly to Norwich - by-passing London to the north. What a relaxed flight for the crew, with land below all the way if they had to land or bail out, for they were over friendly Allied territory. The previous day on their longest flight, it was a constant battle with the terrible stormy weather and a very rough ocean below. Seeing the beautiful English countryside was a first for all the crew.

Bidding farewell to their trusty C-47 the following day in Norwich, the crew was off to London. Hearing V-Bombs going off sporadically through the night was a war reminder that will always be remembered. One night the crew even heard one explode during the performance of love In Idleness, starring the famous acting team of Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne.

Stoke-on-Trent was the location of an air base where the crew spent the next several weeks before being transferred to the 439th Squadron in France. Memories of that base are cloudy because the Day Room was always filled with airmen playing cards. So many smoked that it was difficult to see as well as breathe. Because of this, much time was spent in the barracks writing letters back home or seeing a bit of the British countryside, when permitted off base.

Receiving orders for assignment to the Continent was welcome news for the crew, even though it meant getting involved in the purpose of this trip - to defeat the Axis. Chateaudun, located 80 miles southwest of the Eiffel Tower, was home for the 439th Troop Carrier Squadron. Its purpose was to move troops by plane, pull gliders into combat zones, supply troops near the front lines, evacuate the wounded, and fly released Allied prisoners back to Brussels if they were British, to Paris if they were French, and to Le Havre if they were American.

Home for the 439th was a tent large enough for four single beds. The beds were really army cots, so as many blankets were needed under a person, as on top. It was cold enough in the tent that leaving water in wash basin helmets over night meant that ice had to be knocked out before shaving the next morning. After about a month of shivering all night, the crew of four - pilots Bob Long and Sid Long and navigators Jim Gammill and Hubert (Hugh) Wetzel decided that that was enough. They discovered reusable materials in a bombed mess hall previously used by the Germans when they occupied the air base. The four salvaged materials and transported them by jeep, to an open area near the tent. About two weeks later - working before and after missions - they moved in the 16- foot square "mansion" -complete with built in desk. Two-foot-square plywood panels that came from the States containing nylon glider tow ropes were used for the beautiful panel job inside. With limited past experience and materials, it was a very satisfying accomplishment for the rookie carpenters. Wall decorations included pin-ups of Betty Grable and others less famous, plus our own photos of family and friends.

Not all flights were to the front lines. About once a week several planes would fly to Prestwick, Scotland to bring back new gliders for use later in the war. On one of the trips, Hugh got into Glasgow, not too distant from the Prestwick air base, and purchased a new Raleigh bicycle for $30. That soon became his trusty transportation around Chateaudun. Not able to bring it back home with him, he sold it to a happy Frenchman for $40 before returning to the U. S. in late July.

An astute aviator, Col. Charles H. Young, was the commander of the 439th Troop Carrier Squadron. He began his career at Randolph Field, Texas in 1936 in the Flying Cadet Program. He was the first in his class of 114 to solo and still holds the USAF record for soloing, after just 55 minutes of training.

Chapter 14 of his book, Into The Valley, a 600 page book sub-titled "The Untold Story of USAAF Troop Carrier in World War II," provides a very thorough accounting of the March 24 air invasion across the Rhine at Wesel, Germany - second in intensity to the D-Day invasion of the continent at Omaha and Utah Beaches, on the north coast of France.

Training for the invasion involved more than 50,000 hours of flight time at 12 airfields in France and 11 in England. The C-47's from four airfields each pulled two gliders, using long and short ropes so the gliders were less likely to collide. The 439th was one of the four squadrons to pull two gliders. That meant that 72 C-47's and 144 WACO gliders were lined up on the runway for the take off. The lead planes had lighter-loaded gliders because of the shorter runway length available to them. Col. Young, in the lead plane, needed 200 feet of the wheat field beyond the runway to get his plane and two loaded gliders airborne.

Once in the air, the C-47's, two 1250-horsepower Curtis engines struggled at 130 miles per hour pulling the two gliders more than 400 miles over the French and Belgium country side - from Chateaudun to Wesel, across the Rhine. All was coordinated so that it was a continuous flow to deliver the loaded gliders to a six-mile square area north of Wesel and the Rhine River. Paratroopers jumped into four designated areas and gliders landed in six areas. Col. Young, on page 387 in his book, reported that of the glider pilots on double tow, there were 48 Killed or Missing and 80 Wounded. Casualties among the plane crews that pulled the double tow gliders totaled 27 Killed or Missing and 7 Injured. All the planes that made it back to home bases returned with numerous shell and flak holes. None of the crew in Hubert's C-47 was injured.

The mission across the Rhine was costly, but successful. Just three days later, Hubert was assigned as Navigator on a C-46 mission to fly a Jeep outfitted with complete air control radio equipment to the air base at Frankfort, just captured the day before from the Germans. It was a very rough landing on a runway kissed many times earlier by Allied bombs. As the crew departed for home base, they saw the first cargo plane come in for a landing, controlled with the radio equipment just delivered.

The following week, the flight crews and planes moved from Chateaudun to a forward base at Etian, near Verdun. This shortened the flights to service front-line needs by 300 miles. The city of Luxembourg, being less than 50 miles from Etian, was a temptation that navigators Jim Gammill and Hugh Wetzel could not resist exploring on a non-mission day. Hugh and Jim had never ridden a motorcycle before but that didn't stop them one day. With Hugh at the controls of a borrowed cycle, they made the trip uneventfully, until going down a long decline. Hugh saw a sign advertising ice cream and made a quick turn, hitting the curb - head-on. Passengers flew off and the cycle flipped over. Luckily, the only damage was a bruised right shin for the driver - Hugh.

Most of the six weeks based at Etian were filled with daily flights to airstrips near front lines, hauling in all kinds of supplies, bringing back released prisoners or wounded. Those Americans were taken to Le Havre to board a ship back to New York. Movement of troops intensified after V-E Day, May 7,1945.

By late June 1945, the 439th Troop Carrier Squadron moved back to home base at Chateaudun. We were happy to reoccupy the 256 square foot "mansion" we had created almost three months earlier. When given the opportunity for their first three day R & R since arriving in France, Jim Gammill and Hugh Wetzel chose Paris - the famous city they had seen scores of times from the air, or the airport 6

when delivering released French prisoners returned from the German prison camps overrun by the Allies.

For two nights in Paris, Jim and Hugh were billeted in the famous Crillion Hotel near the American Embassy, Eiffel Tower, and Arc de Triomphe. Sight-seeing, a movie, a dance, restaurant food, sleep in a real bed, and even a fireworks display on July 4th, were special highlights - remembered to this day.

Once back at Chateaudun, the 439th Squadron had packing chores in preparation for their return to the States. Saying goodbye to their trusty C47's, crews were assigned to fly the newer, larger (2000-horsepower engine) C- 46's back to Westover Field, Massachusetts, by way of Reykjavik, Iceland (at the East-West airbase on the southwestern tip), Goose Bay, Labrador, and Bangor, Maine. Each stop was more exciting than the previous one, since it was a flight closer to home. At Westover, crew members turned over their C-46 planes and personal equipment, such as navigation sextants and watches, never-used 45 caliber revolvers, and flight gear.

Memories of long-past train rides came back quickly as the crew boarded a troop train near Boston for the trip home and a 30 day furlough. For Hugh that was St. Louis, after more than 1200 miles of train track scenery. Home, he was rejoined with family, friends, and good home cooking for the next four weeks. About the time the new assignments arrived with orders to report to Merced Field, California, two atomic bombs had been dropped - the first, August 6 on Hiroshima, Japan and a second, August 9 on Nagasaki. On September 2, 1945, the cease-fire agreement was signed, thus ending the war with Japan and the need for more Air force crew assignments to war zones.

Hugh reported to Merced as assigned. His brief stay at Merced included a trip to beautiful Yosemite National Park - a dusty, jolting 40 mile ride with about 40 soldiers in the back of an army truck. Everyone was in good spirits at this point, knowing that the war was virtually over. The final six weeks of duty for Hugh included a return to the mid-west to the Troop Carrier Base at Warrensburg, Missouri. Some furlough time followed, after which navigator Hubert Wetzel received an honorable discharge with the rank of 2nd Lt. in the Army Air Corps, at Scott Air Force Base, Belleville, Illinois. This was just 35 miles from his home town, Alhambra, Illinois. Hugh had been a Yankee Doodle guy for three years and two weeks, since enlisting in ASTP at the University of Illinois, back in November 1942.

Hugh was proud to be a called a "fly-boy". Despite the war, his military service was the greatest experience of his 80 plus years. He is glad to be a veteran, and thankful to be alive today to tell about it. He served his great country in the best way he could then, and fully supports the service men and women who continue to defend the American people, borders, and interests, today.

Wall of Honor profiles are provided by the honoree or the donor who added their name to the Wall of Honor. The Museum cannot validate all facts contained in the profiles.

Foil: 24