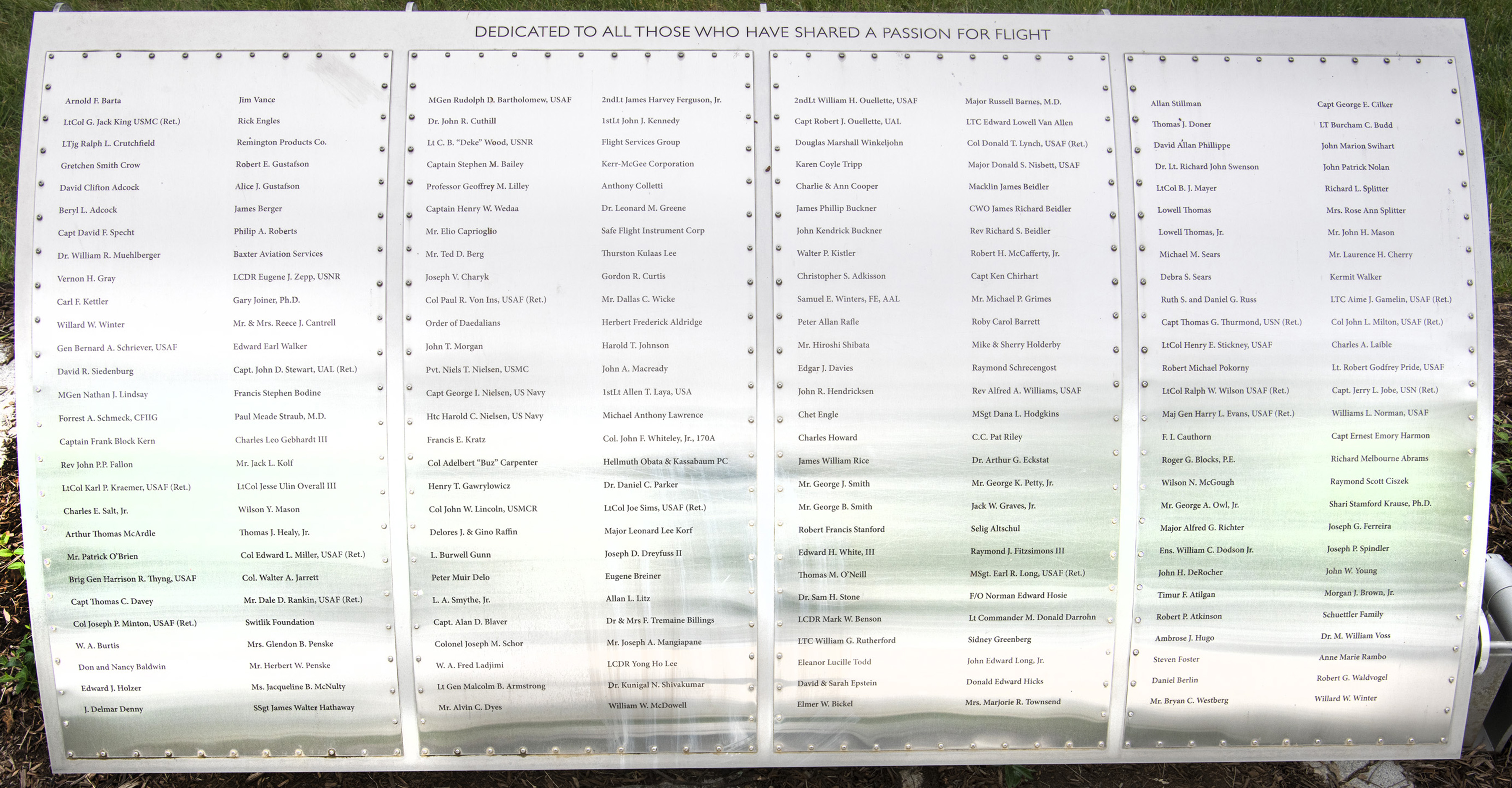

John Edward Long Jr.

Foil: 26 Panel: 3 Column: 2 Line: 26

Wall of Honor Level: Air and Space Sponsor

Honored by:

Mr. Robert P. Hudgens

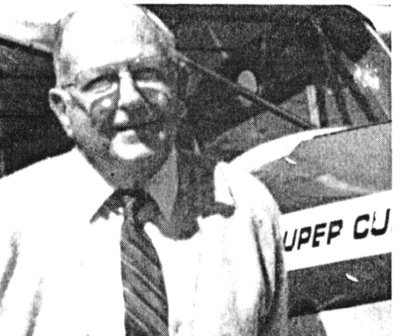

With the quiet dignity so endearing to his friends, John Edward Long, Jr., a revered figure in aviation, holder of the Guinness Book of World Records mark for more flying time as a pilot-in-command than any other person in the world, slipped over the western horizon at 2120L on July 17, 1999 in a Montgomery, Alabama hospital. He put his last entry in a record-setting logbook on June 21, 1999, as an observer on a routine patrol inspecting power lines for the Alabama Power Company. Long logged 64,397 hours — that's seven years spent in the air, and he filled 14 logbooks.

Most of those hours were hand-flown, single-pilot, stick-and-rudder hours flown at about 100 feet above the ground. For over 40 years, Long inspected power lines throughout Alabama from the vantage point of a low-flying airplane cockpit. More than 40,000 of his 57,000 hours were logged on power-line patrol.

Born November 10, 1915, in Montgomery, Alabama, Ed spent his entire life, with the exception of service during World War II, in his hometown. As a youngster, he was fascinated by the aviation pioneers of the 1920s and 1930s, particularly Charles Lindbergh and Wiley Post. He greatly admired Lindbergh's feat, not because of the feat itself, but because "he had the guts to do it," and he regarded Post as one of the great aviators in the world.

With fifty cents his grandmother gave him, Ed took his first ride in a Ford Tri-Motor at the age of fifteen. In 1933, at the age of seventeen, he took his first lesson in an old Curtiss Robin. "Took me three years to solo with a total of an hour and forty minutes over that three year period," he said in an interview. That solo was in 1936 in a Taylor E-2 Cub, the beginning of a life-long love affair with that vulnerable airplane. With jobs and money scarce during the Depression, he wrangled a job at a local flying school washing airplanes, receiving thirty minutes flying time for a week's work. He earned his pilot rating, Certificate #44202, on December 14, 1939, having logged 63 hours at the time.

In 1940, Ed joined the Army Air Corps in hopes of becoming a pilot, but, at 115 pounds, was told, "Long, you don't weigh enough." He didn't meet the Army's minimum weight standard, so he spent the war as an aircraft mechanic, inspector, and a B-24 crew chief, rising to the rank of master sergeant. He mustered out of the Army in October 1945, a grand total of 400 flying hours to his credit, and went to work as a pilot and mechanic at the now long gone Normanbridge airport in Montgomery, AL. He eventually wound up with Montgomery Aviation at Dannelly Field in Montgomery, AL where he worked as a charter pilot, corporate pilot, and flight instructor, and later was Vice President.

In 1953, through a Montgomery Aviation contract with Alabama Power Company, he began flying a PA-18 Super Cub over Alabama Power's transmission network across the Southeast to inspect the lines. Although he flew other aircraft, the Super Cub was his favorite. The view was equally good out the left or right side; endurance was better than that of the coffee-drinking pilot; and on those steamy Alabama summer days "it sure felt good to pop open the window and lower the door." Flying at altitudes of less than 200 feet, he flew eight hours a day, five days a week for the next 46 years. He rarely missed a flight. At that rate, he quickly piled up hours in meticulously kept logbooks. In March 1992 Alabama Power Company awarded Long a pin studded with four diamonds in recognition of his 40 years of scanning all those miles of power lines and utility poles for broken and flashed insulators, bad crossarms, rotten poles, woodpecker holes, and right-of-way encroachments.

Over the last ten years of his life, except when he ran into his physical problems, Ed averaged 1200 hours a year, extending his own record to the final tally of 64,397 hours. Remarkably, over 50,000 of those hours were spent hand flying his favorite Piper Super Cub, an aircraft ideally suited for patrolling the power lines.

For all his flight time, Long had a remarkably incident-free record. He had near-collisions with a turkey and an F-4 practicing nap-of-the-earth maneuvers. He once bent a landing gear, wing tip, and propeller on a hidden rock after landing in an open field to retrieve another airplane that had made a forced landing. And he had a successful dead-stick landing on a two-lane road in a Bonanza with a seized engine.

Long set his own schedule, sometimes flying for 30 minutes to an hour a day, sometimes much longer. Minimum weather conditions included surface winds of less than 15 knots, 1 mile visibility, and clear of clouds. If the hills were not shrouded in cloud, it was a go. He was not instrument rated—if all of your flying is at 500 feet or lower, an IFR ticket is of little use. But the weather can change fast, especially in winter. That's when Long's experience came into play. "The main thing is to know the terrain and the location of every emergency landing site if the weather comes down," he explained. His biggest scare came decades ago when he and an observer were patrolling underneath a lowering ceiling. Long wanted to turn back, but the observer, who also was a pilot, urged him to press on to an airport that was just ahead. Suddenly, they were engulfed in cloud. Long started to execute a turn but thought better of it considering their low altitude. He climbed and soon was on top. Then he spotted a hole, spiraled back down under the clouds and, in very low altitude slow flight, followed a highway back to home base. That experience taught him the lesson of a lifetime.

He served as President of the Montgomery Air Safety Council, President of the Alabama Wing of the 0X5 Club, a member of the Silver Wings Club, the National Aeronautics Association, and the Montgomery Aero Club. He was inducted into the Alabama Aviation Hall of Fame and was recognized and honored many times for his contributions to the aviation industry and to the Montgomery and Alabama communities.

Ed's attitude toward safety was established early in his flying career. On the inside cover of the first of his thirteen logs covering 63 years is a handwritten entry "My Motto: It is better to be an old pilot than to be a bold pilot. Fly Safe." On each page of those first logs was the note "Fly safe."

Wall of Honor profiles are provided by the honoree or the donor who added their name to the Wall of Honor. The Museum cannot validate all facts contained in the profiles.

Foil: 26

All foil images coming soon.View other foils on our Wall of Honor Flickr Gallery