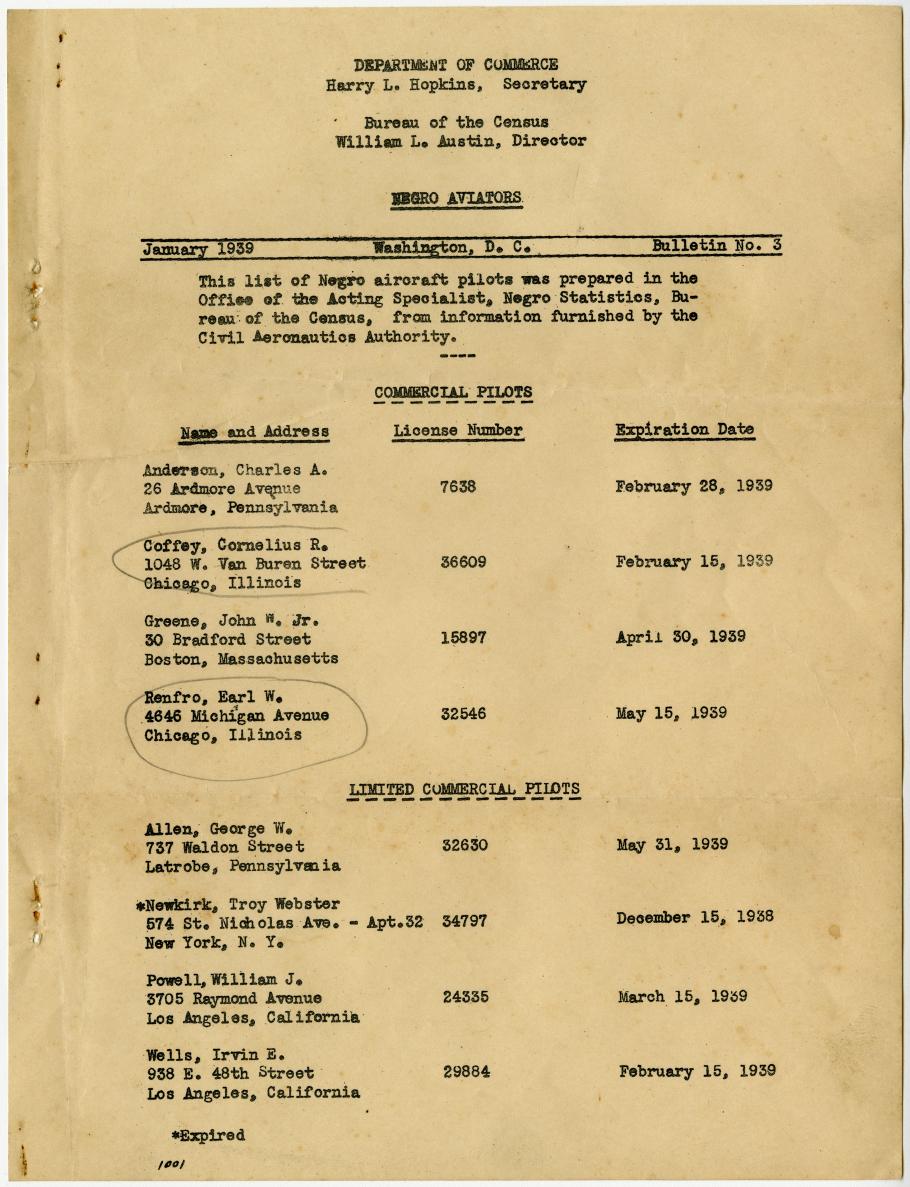

Dale L. White Sr., was a prominent African American pilot, best known for his 1939 “Goodwill Flight” with Chauncey Spencer from Chicago to Washington, DC, to make the case for African American participation in flight training, both civilian and military. His flight illustrated the challenges that African Americans faced in reaching equality and the inconsistency in how pioneers like White were treated.

Born in 1899 in Minden, Louisiana, White moved to Chicago, Illinois, in 1930. In 1932, he began his studies at the Curtiss Wright Aeronautical University, the first accredited flight school in the Midwest to admit black students and to hire black instructors. On August 18, 1933, White began his flight training and he received his pilot’s license in June of 1936.

For the next decade, White was very active in Chicago African American flying circles and was a member of the Challenger Air Pilots Association (CAPA), a group organized by Chicago-area African American aviation enthusiasts.

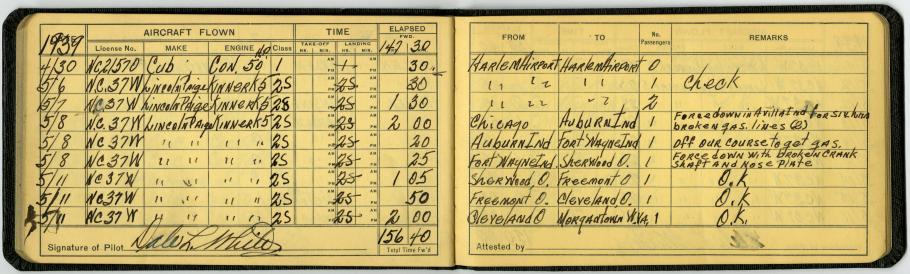

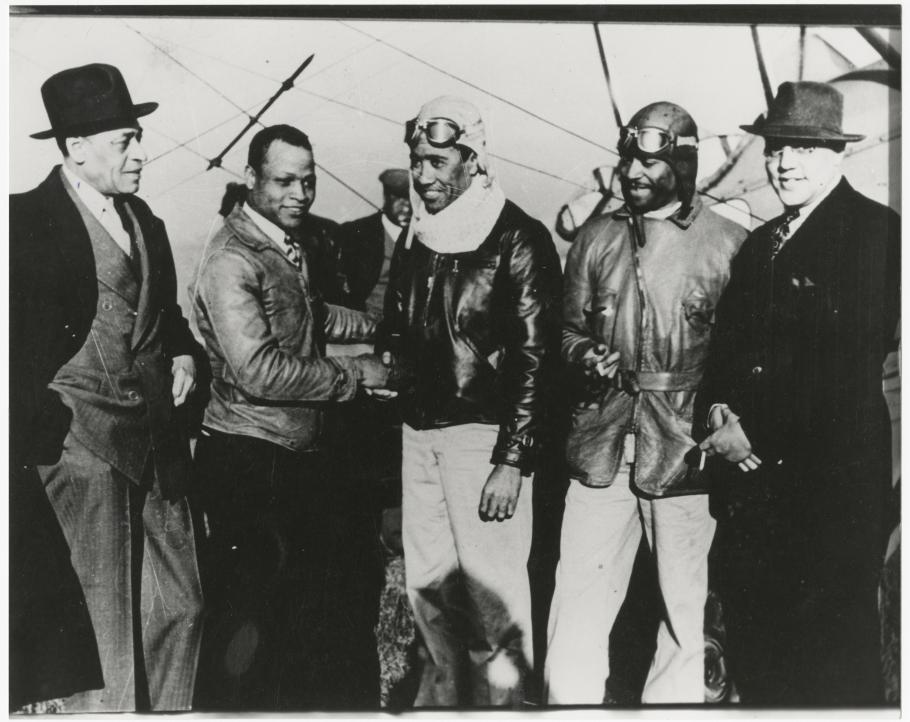

In the spring of 1939, the CAPA and the Chicago Defender, the local African American newspaper, decided to organize a "Goodwill Flight" to Washington, DC, to lobby for a change in legislation so African Americans could join the US Army Air Corps. Dale White was chosen to be the pilot of the flight and Chauncey Spencer was selected as the navigator. With a CAPA-secured rental of a Lincoln PT-K biplane, White and Spencer left Chicago on May 8, 1939, for their 4,828 kilometer (3,000 mile) round-trip.

Dale L. White’s pilot logbook provides insight into the flight. May 8 was a difficult day. First, they were “force[d] down in Avilla, Indiana, for six hours due to broken gas lines.” Later that day, White notes that they were “force[d] down with broken crank shaft and nose plate” in Sherwood, Ohio. The Millers, on whose farm they landed, greeted them warmly and the aviators were guests at the local tavern until repairs were complete on May 11.

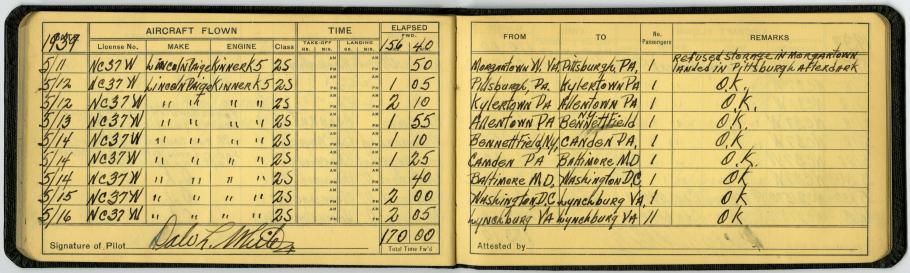

In the first entry on the second page, White notes in the May 11 “Remarks” section, “Refused storage in Morgantown landed in Pittsburgh after dark.” Without lights on their aircraft, White and Spencer followed a Pennsylvania-Central Airlines transport to the Pittsburgh airport. This was a dangerous move and the two were fortunate that the Civil Aeronautics Authority allowed them to continue the next day.

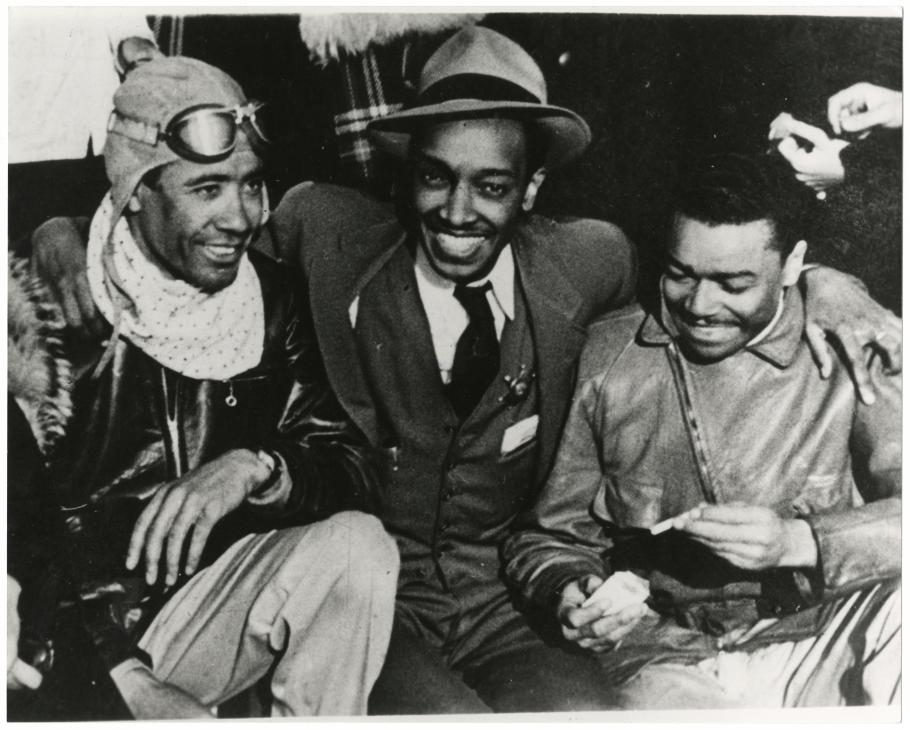

Though they may have been unknowns to the welcoming Millers in Sherwood or to the people of Morgantown, West Virginia, where they were rejected, White and Spencer’s cause and flight were well known to the African American community in New York. During their stop in the Big Apple, the two attended boxer Joe Louis’s 25th birthday party on May 13 at the Mimo Club.

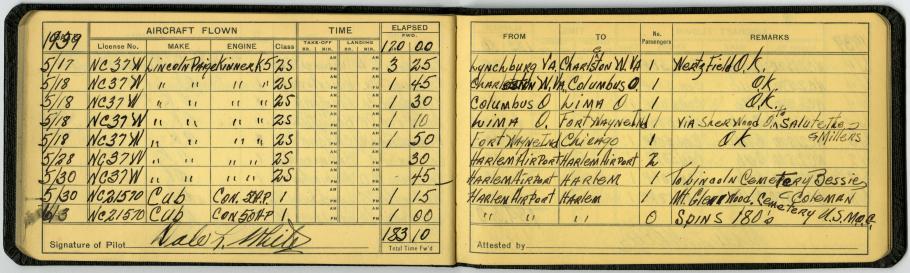

The next day, White and Spencer landed in Washington, DC. They had scheduled meetings with Senators James Slattery and Everett Dirksen. But perhaps a chance meeting with then-Senator Harry S. Truman had the most lasting impact. Upon meeting them, Truman reportedly commented, “If you guys had the guts to fly this thing to Washington, I've got guts enough to see you get what you are asking.” Indeed, Truman did help pass legislation allowing African Americans to participate in the Civilian Pilot Training Program. In 1948, President Truman integrated the armed services by presidential order.

White and Spencer returned to Chicago in a roundabout way. They stopped by Spencer’s hometown of Lynchburg, Virginia. They then made a special pass over Sherwood, Ohio, to salute their new friends, the Millers. And they returned to Chicago as heroes.

On May 30, White was chosen to drop a wreath on the grave of aviator Bessie Coleman, located in Lincoln Cemetery, Chicago.

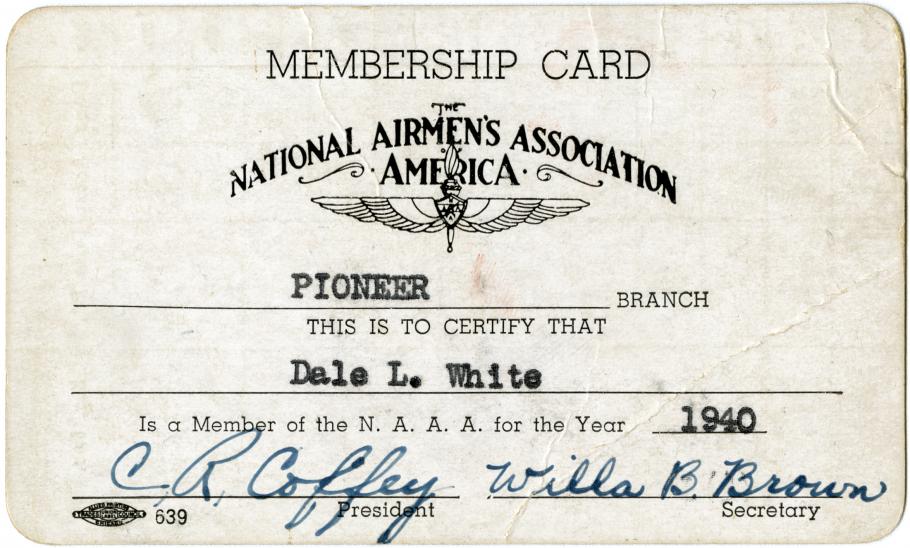

In August of 1939, the CAPA broadened its scope and was incorporated as the National Airman's Association of America (NAAA). White was elected to be vice president.

In 1940, White became an aircraft mechanic at Wright-Patterson Field in Dayton, Ohio. Even then, his race made the application process difficult as he received conflicting information about how to apply for and accept positions. When the United States entered World War II, White did not join the Tuskegee Airmen, as he was too old to apply. He did continue to fly until June 1941, when he quit flying at the request of his wife. He retired from Wright-Patterson in 1971 and died in 1977.

The National Air and Space Museum Archives holds the Papers of Dale L. White Sr., at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia. In addition to White’s flight logs, he saved a scrapbook about the African American aviation community in Chicago, especially John C. Robinson, “The Brown Condor of Ethiopia.” White also kept his payment books, weather forecast maps, and coursework notes from studies at Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical University. Chauncey Spencer’s flight suit, goggles, helmet, and scarf are on display in the Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight Gallery at the Museum in Washington, DC.

Related Topics

You may also like

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.