Happy Birthday, Sir Arthur C. Clarke

Dec 16, 2017

By Martin Collins, Space History Department, and Patricia Williams, Archives Division

Dec 16, 2017

By Martin Collins, Space History Department, and Patricia Williams, Archives Division

Today would have been visionary science fiction writer Sir Arthur C. Clarke’s 100th birthday (1917-2008). In the many decades since his first writings, his renown and influence still reverberate, motivating a range of contemporary thinkers—in science fiction and literature, science and engineering, film, futurism, and the cultural history of the mid to late-20th century. As an intellectual, openly and actively engaging challenges of the historical moment in which he lived, he continues to fascinate.

Yet, despite his status as a public figure, might we benefit from a fuller view of his life and work?

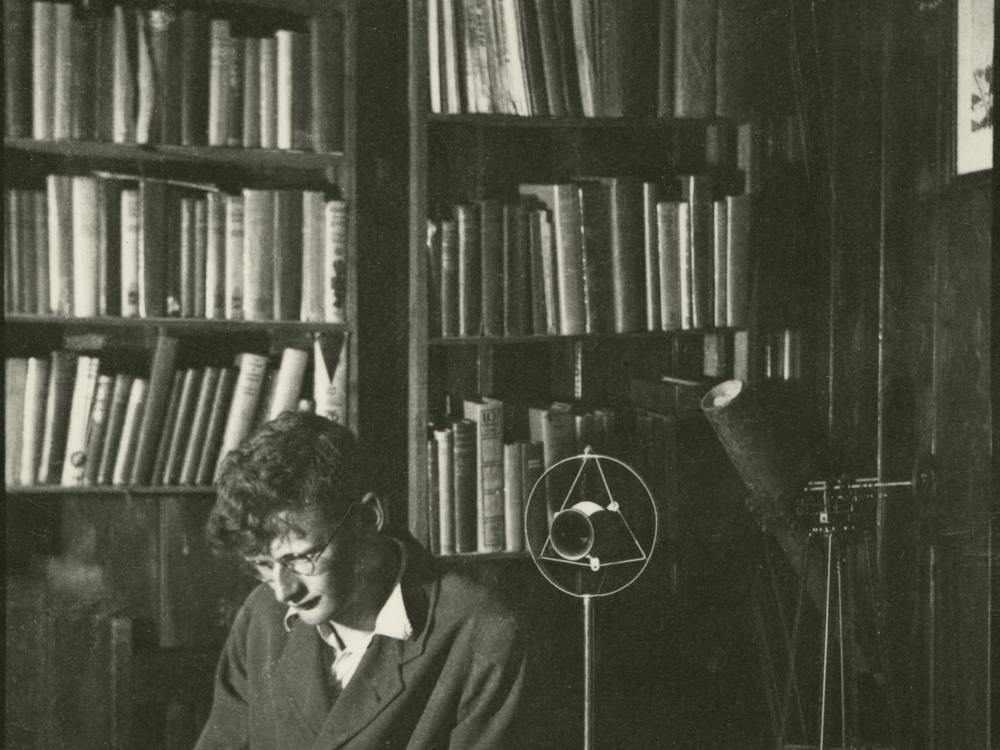

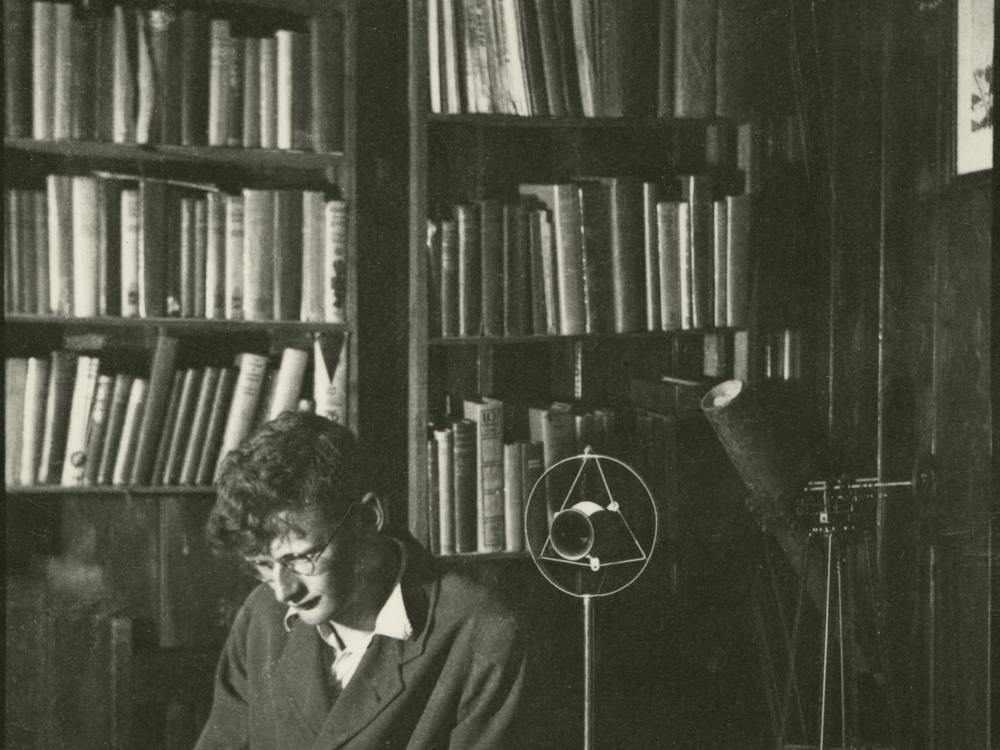

Even now, years after his death, the world-famous author’s office at his home in Colombo, Sri Lanka, is as it was during his life. Books, including his own, line the walls. Videos of his many public appearances and TV discussions sit in neat rows. One title jumps out: God, the Universe, and Everything Else, featuring Clarke, Carl Sagan, and Stephen Hawking.

On the walls hang photos of luminaries who came to visit, including an autographed studio photo of Elizabeth Taylor and, of course, photos of astronauts inscribed with homages to Clarke’s influence on their lives. Also prominent are photos and memorabilia of his life in Sri Lanka, where Clarke had resided since 1956.

A comfortable sofa and chairs provide a setting for talking with the many local and international visitors who came to see him—like the photos, a marker of the range of his personal connections extending across continents. Commanding one side of the room: his desk, uncluttered, featuring a photograph of him and the Sri Lankan family with whom he made a home through several decades. As a seat: his wheelchair, a necessity after the onset of post-polio syndrome in the late 1980s. To its right: a rank of large windows, usually open to the tropical air, bird song and the playful chatter of young students at the girls’ school next door filtering in.

This, too, is how his office looked and felt in 2014 when we went to Colombo to arrange for the donation of Clarke’s papers to the Smithsonian. And it’s how it looked in the years before that.

One beneficial aspect of the Clarke archival collection is that it captures the deep entanglements of his life. As the sketch of his office suggests, one compelling question is how to understand the meaning and impact of Clarke’s intimate, decades-long immersion in the culture of Sri Lanka. In what ways did his training and deep commitment to the Western traditions of science, technology, and humanism intersect with Sri Lanka, a nation only gaining its independence in 1948? How might his Sri Lankan life have shaped his intellectual outlook? How did his presence enter into Sri Lankan politics and policy (even well after his death Clarke’s face was prominently featured on the Sri Lankan embassy’s web homepage)?

Arthur Clarke at ease, near the beach in Sri Lanka, leaning on his car, early 2000s. By the time of this photo, Clarke had already lived in Sri Lanka for more than 40 years.

Although he never became a citizen of Sri Lanka, Clarke had a deep affection for his adopted country and for South Asia. One small indicator, among many, was Clarke’s collaboration with the Sri Lankan government to establish the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Modern Technologies in 1984 to facilitate local training in engineering, especially those related to communications—a capability Clarke saw as transformative of the human condition on a global scale. This story and the contours of his everyday experience in Sri Lanka suggest the value of a closer look at his life in full.

Clarke and a Sri Lankan colleague on the construction site for the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Modern Technologies, 1983. Note in the background the communications satellite antenna—a direct link to Clarke’s 1945 conceptualization of geostationary communication satellites. Clarke saw satellite communications as a special resource for developing countries.

On Clarke’s centenary, it is only fitting to end with one of his quotes—a literary form at which he excelled.:

“In my life I have found two things of priceless worth - learning and loving. Nothing else - not fame, not power, not achievement for its own sake - can possible have the same lasting value. For when your life is over, if you can say 'I have learned' and 'I have loved,' you will also be able to say 'I have been happy.”

Happy Birthday, Sir Arthur.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.