How Being Deaf Made the Difference in Space Research

Apr 07, 2017

By Jean Lindquist Bergey, Guest Contributor

In the late 1950s, researchers faced many unknowns about the effects of space travel on the human body. How would motion sickness impact the ability of astronauts to function and survive? To better understand and manage potential dangers, they looked to the Deaf community.

The U.S. Naval School of Aviation Medicine and the newly formed National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) recruited deaf people for weightlessness, balance, and motion sickness experiments. Researchers selected test subjects that met specific criteria. All but one of the selected test subjects became deaf from spinal meningitis, which impacted their inner ear physiology. This meant they could endure motion and gravitational forces that make most people nauseous. The ability to withstand intense movement turned the so-called “labyrinthine defect” into a valuable research asset—no matter the test of equilibrium, the deaf participants simply never got sick.

In the late 1950s, the U.S. Naval School of Aviation Medicine and the newly formed National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) recruited deaf people for weightlessness, balance, and motion sickness experiments.

From 1958 to 1968, 11 deaf men joined the research effort led by Dr. Ashton Graybiel from the U.S. Navy. Other deaf people, including one woman, briefly joined the study. The core group was known as the “Gallaudet Eleven” because they came from Gallaudet University in Washington, DC—a university dedicated the education of students who are deaf. The group participated when called upon and remained involved in the research for many years. On April 11, 2017, Gallaudet University will open Deaf Difference + Space Survival, an exhibition that shares their story. The exhibition is a collaboration between Gallaudet University’s students and staff; the University’s museum; and five of the original Gallaudet Eleven participants.

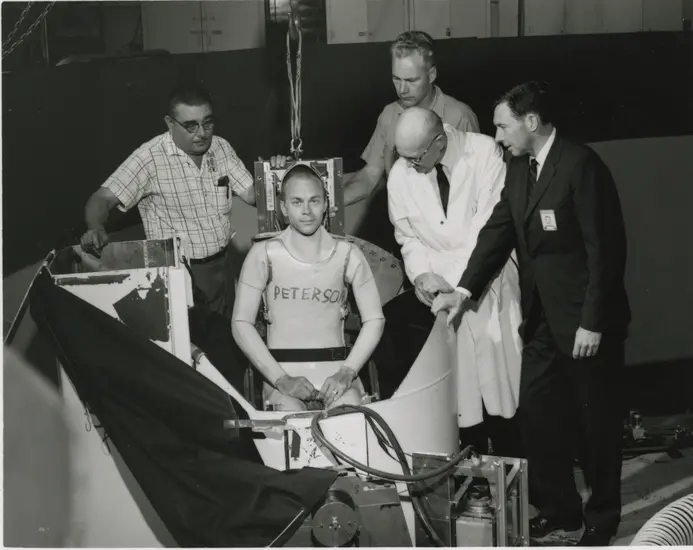

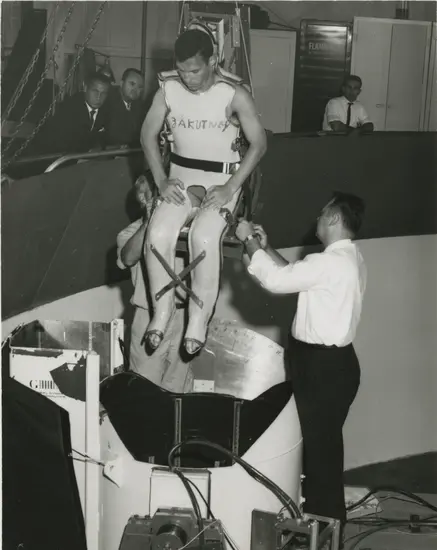

The Gallaudet Eleven provided an opportunity for researchers to observe how the human body and mind functions in extreme conditions. Experiments included whirling in water-filled tubs, spinning in centrifuges while bolted into body casts, and tipping in contraptions that held their heads steady while cameras snapped ocular photographs. Weightlessness flights, each with multiple zero-gravity episodes, tested body orientation and gravitational cues. Counter-rolling of the eyes, or lack thereof, was documented during several aerial maneuvers to record individual responses to weightlessness.

Researchers measured test responses in every conceivable way. Blood and urine tests, along with blood pressure recordings and heart monitors measured physical reaction to motion and gravitational force. Photographs tracked eye movements. Leveling devices, set and reset during rolling and tipping, showed the perceived horizon. Deaf participants also documented their sensations and shared perspectives with the research team.

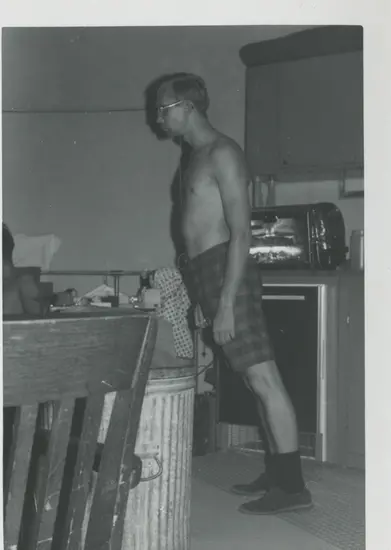

For 12 days, four of the test subjects lived in a circular room rotating at 10 revolutions per minute. They performed hours of physical and cognitive tests per day and at night slept with their heads to the center of the circular room like spokes on a wheel. The rotation room, 6 meters (20 feet) in diameter, had a full complement of test equipment and the necessities for living—a sink, refrigerator, stove, shower, and toilet. The room stopped its revolutions only for delivery of supplies and for Navy researchers to enter in the morning and exit in the evening. Tests measured the men’s ability to retain and record sequences of numbers, as well as perform dexterity and balance exercises while spinning.

A few of the Gallaudet Eleven performed even more surprising tasks. One, for instance, rode the Empire State Building express elevator up and down continuously for hours to see how it might affect balance. Another had to draw his own blood while spinning in a centrifuge pod. A third wrote his signature over and over as air was removed from the sealed testing room; he received oxygen when his scribbles became illegible. Several rode through a violent storm with 40 knot winds on the icy North Atlantic. It was a tumultuous voyage and, ironically, experiments on board had to be cancelled because the research staff became motion sick. The deaf men were unaffected and played cards. Enjoying the heave and sway of the ship, they watched a porthole as stars outside appeared to jump up and down, left and right in the night sky.

“We were different in a way they needed.”

Harry Larson, one of the research participants, explained, “We were different in a way they needed.” Indeed, their difference made it possible for researchers to explore human reactions to weightless environments and extreme motion and to better understand the complexity of entangled human sensory systems.

With a spirit of adventure and sense of patriotic duty, the Gallaudet Eleven endured physically, cognitively, and psychologically challenging tests that most people could not. Their participation has been a source of great personal pride, a unique contribution they could make because of, not in spite of, a physical trait. Now, the public can share in their story of dedication and difference.

The Gallaudet Eleven

Harold Domich

Robert Greenmun

Barron Gulak

Raymond Harper

Jerald Jordan

Harry Larson

David Myers

Donald Peterson

Raymond Piper

Alvin Steele

John Zakutney

Other deaf people known to have participated for brief studies:

Pauline Register Hicks

James Bischer

All images courtesy of Gallaudet University Archives, collections of Jerald Jordan, Barron Gulak, David Myers, and Harry Larson.

This guest post comes from Jean Lindquist Bergey, associate director of the Drs. John S. & Betty J. Schuchman Deaf Documentary Center and curatorial advisor for the exhibition Deaf Difference + Space Survival at Gallaudet University.

Related Topics

You may also like

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.