Feb 15, 2016

Lots of museums and historical institutions have letters from George Washington and Abraham Lincoln in their collection, but why would a museum dedicated to aviation, space exploration, and planetary science? Ballooning, that’s why.

The advent of human flight started in June 1783 in France. Two brothers named Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Etienne Montgolfier demonstrated the first hot-air balloon flight with no passengers, followed by flights carrying animals, and, finally, a tethered flight with humans aboard. The first free flight with human passengers took place on November 21, 1783. Among those on hand in Paris to witness some of these balloon ascensions were Benjamin Franklin, the members of the John Jay and John Adams families, including 16-year-old John Quincy Adams, and a surgeon friend of Franklin’s, John Foulke.

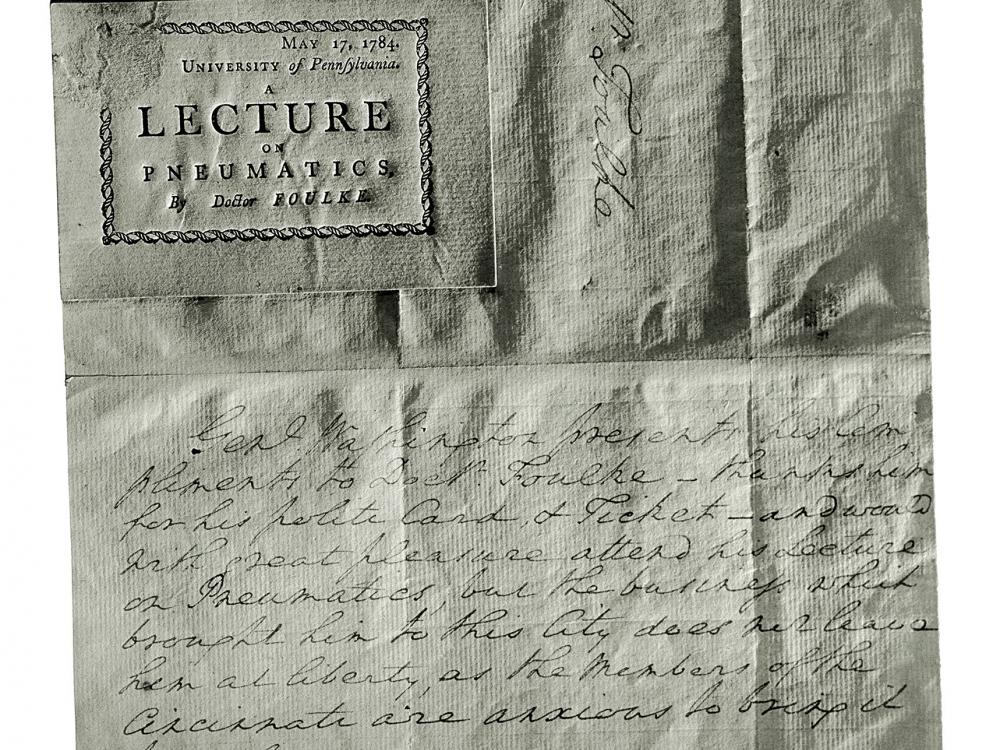

As National Air and Space Museum historian Tom Crouch notes in his book Eagle Aloft: Two Centuries of the Balloon in America, Foulke returned home to Philadelphia, where he flew small paper hot-air balloons that rose to “perhaps three times the height of the houses and then gently descended without damage.” He also arranged a lecture on ballooning at the University of Pennsylvania. Foulke sold tickets to the lecture and passed out complimentary invitations to important individuals, including General George Washington. Washington, who was not yet president, wrote this letter to Foulke dated May 17, 1784, declining the invitation with regret due to prior commitments:

“Genl. Washington presents his compliments to Doctr. Foulke — thanks him for his polite card and ticket — and would with great pleasure attend his Lecture on Pneumatics, but the business which brought him to the city does not leave him at Liberty, as the Members of the Cincinnati are anxious to bring it to a close Monday Morning.”

(Note: the “the Cincinnati” referred to is the Society of the Cincinnati, an organization dedicated to preserving the ideals of the officers of the American Revolutionary War.) Attached to the note was the unused ticket.

Although he did not attend the lecture, his interest in ballooning continued. As President, Washington not only viewed but also assisted with the first American ascent of the famous French balloonist Jean-Pierre Blanchard on January 9, 1793 in Philadelphia. Besides President Washington, future presidents John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe also observed the event. The National Air and Space Museum Archives collection contains not only the letter but the lecture ticket, both in the same frame. Now jump ahead to June 11, 1861, when Smithsonian Secretary Joseph Henry introduced American balloonist Thaddeus Lowe to President Lincoln. Henry had assured the president of Lowe’s aeronautical skills. Lowe had a plan to demonstrate to President Lincoln that gas-filled observation balloons could be used effectively for battlefield reconnaissance.

He made several tethered ascents in front of the Columbian Armory, located where the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC sits today. On June 16, 1861, Lowe made his final demonstration — an ascent to 152 meters (500 feet) — in his balloon Enterprise, with telegrapher Herbert Robinson and supervisor of the telegraph company George Burns in the basket with him. From his perch above the nation’s capital, Lowe sent the first-ever telegram from the air. It read:

Balloon Enterprise Washington, D.C. 18 June 1861 To President United States:

This point of observation commands an area near fifty miles in diameter. The city with its girdle of encampments presents a superb scene. I have pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station and in acknowledging indebtedness to your encouragement for the opportunity of demonstrating the availability of the science of aeronautics in the military service of the country.

T.S.C. Lowe

This illustration shows Thaddeus S.C. Lowe’s balloon ascension from the grounds of the Columbian Armory (now the site of the National Air and Space Museum), June 18, 1861. It was sponsored by Smithsonian Secretary Joseph Henry, and Lowe made the first telegraph message from an aircraft.

Back on terra firma, Lowe went to the White House to meet with the president again, where the two discussed balloon reconnaissance until the early hours. Lincoln even invited Lowe to spend the night at the White House so they could have breakfast together and continue their discussion. Later that summer, Lincoln approved the establishment of the Union Balloon Corps, but not everyone on the president’s staff was convinced of project’s efficacy. One skeptic was Lt. General Winfield Scott, commander of Union forces, and on July 25, 1861 the president wrote this note to Scott:

At President Lincoln’s insistence, the project moved forward. Enterprise, the balloon Lowe had used for the demonstration flights, gave way to seven new balloons funded by the army: Intrepid, Constitution, United States, Washington, Eagle, Excelsior, and the Union. The balloons varied in size, but each was capable of rising to the end of a 1,520 meter (5,000 feet) tether. Union aeronauts made some 3,000 flights during the Balloon Corps’ existence. Balloon surveillance was used for map making, locating Confederate positions, and conveying live reports during battle.

View of Union soldiers on the ground holding tether lines while Thaddeus Lowe ventures aloft in the balloon Intrepid during the Battle of Fair Oaks May 31 and June 1, 1862. A Union camp can be seen in the background.

Disagreements between Lowe and his military supervisors led to the end of the balloon experiment in 1863. Confederate General James Longstreet was among those who breathed a sigh of relief, noting that southern commanders had been forced to mask their troop movements and spend resources and time camouflaging their encampments because of the Union “eyes in the sky.” Kathleen Hanser is a writer-editor in the Office of Communications at the National Air and Space Museum.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.