Project Paperclip and American Rocketry after World War II

Mar 31, 2023

By Michael Neufeld

Project Paperclip was the second name for a program to bring German and Austrian engineers, scientists, and technicians to the United States after the end of World War II in Europe. Known by many today as “Operation Paperclip,” which is actually a misnomer, it was originally called Project Overcast. Its official objective was to bring these experts to the United States for six months to a year to help America in the war against Japan. But that war suddenly ended in August 1945 and the program continued anyway. In fact, the U.S. armed forces and civilian agencies sought long-term advantages for the United States through the seizure of Third Reich technologies that they saw as superior to, or competitive with, Allied ones—notably aircraft, rockets, and missiles. The people who had invented or designed these weapons were needed to help transfer the technology. So what began as a short-term advisory project quickly evolved into a program of permanent immigration.

Many of Project Paperclip's scientists and engineers had Nazi records, which were seen as an inconvenient problem by the project's administrators. Roughly half of the early Paperclip specialists had been members of the Nazi Party, many opportunistically. A minority were true believers who had significant party records or had joined the SS (Schutzstaffel), or SA (Sturmabteilung) also known as Brownshirts for their brown uniform. The rapid deterioration of relations with the Communist-run Soviet Union, which by 1948 led to a Cold War that threatened to turn hot, made the immigration of ex-Nazis more palatable to the American government and public. It became easier to sweep their past under the rug. The argument was that we needed them for our weapons programs or, at the very least, we needed to deny their knowledge and talents to the Soviets.

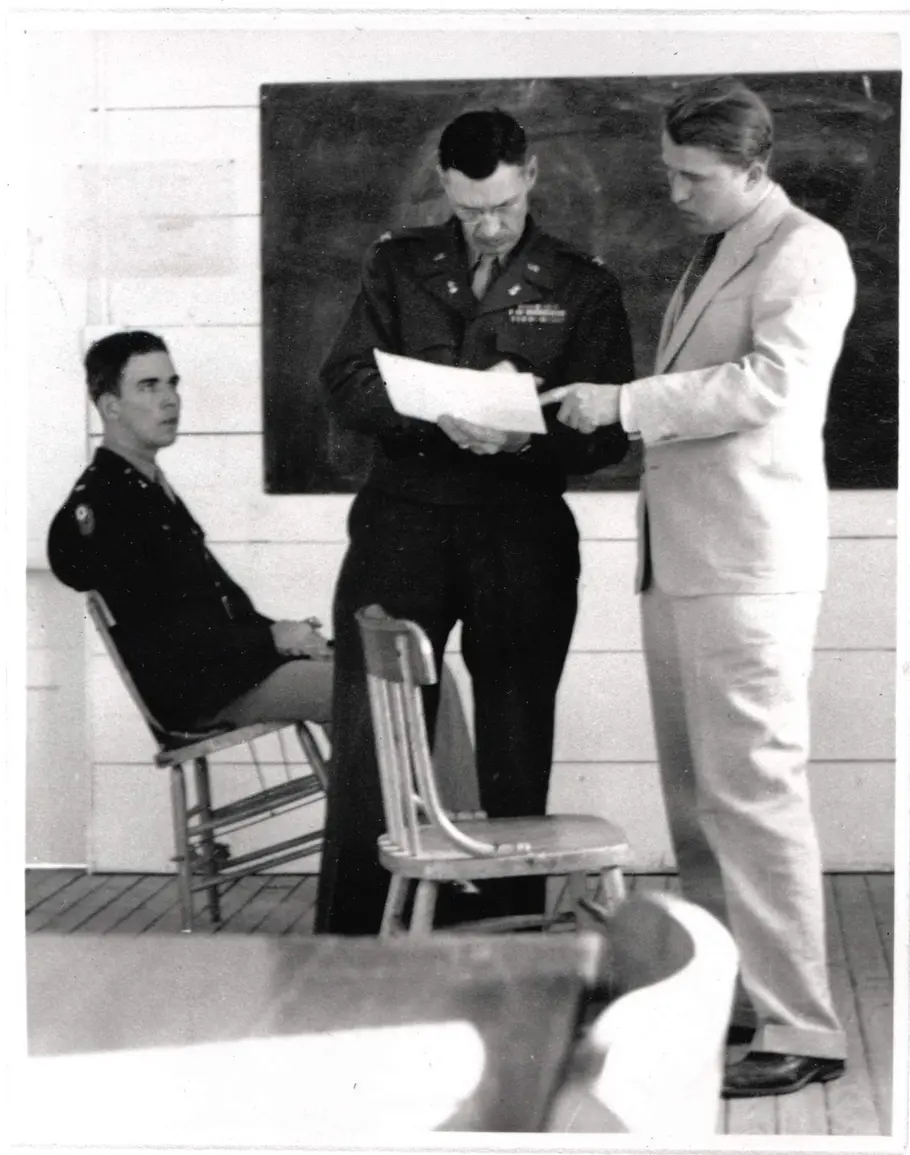

A case in point was the V-2 ballistic missile group led by Dr. Wernher von Braun. He had been a party member and SS officer and was at least tangentially involved in the murderous exploitation of concentration-camp prisoners in missile production, as were several associates. The U.S. Army kept that information classified and brought von Braun and about 125 colleagues to Fort Bliss, outside El Paso, Texas. The Germans helped Americans launch V-2s and were tasked with developing an experimental cruise missile. In 1950, von Braun’s group was moved to Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, and became the heart of the Army’s nuclear-armed ballistic missile development. In his spare time, von Braun made himself world-famous by advocating spaceflight in magazines and on TV. Soon after the Soviets launched Sputnik in October 1957, he and his German-led group, now numbering in the thousands (almost all native-born Americans), helped launch the first United States satellite, Explorer I. In 1960, von Braun’s division of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency was transferred to a new civilian space agency, NASA. The Huntsville Germans, most naturalized in 1954-1955, went on to lead the development of the Saturn rockets that put Americans on the Moon in 1969.

That spectacular Cold War story has long overshadowed the project to the point that, even today, members of the general public and the media often equate the von Braun group with Paperclip. In fact, the Huntsville Germans, numbering closer to 200 by the mid-fifties thanks to later arrivals, were never more than 15 to 20 percent of Paperclip’s intake. The U.S Air Force, not the Army, brought over the most experts, and other specialists went to Navy facilities or those of the Commerce Department and private companies. It was part of a broad program to exploit German science and technology, one that paralleled projects in the Soviet Union, Britain, France, and several smaller countries. Most Paperclip specialists were dispersed as individuals or small groups to military laboratories, universities, and private companies, with the result that they did not have the public profile of the Huntsville Germans.

Another common fallacy is that von Braun’s group, and by extension, all the Paperclip arrivals, came to help the United States space program. But before the Eisenhower Administration started the Vanguard satellite project in 1955, there was no space program. The aerospace specialists, who constituted most of the Paperclip program, were here to help the United States in the rapidly developing arms race with the Soviet Union. Notable areas of focus were guided missiles, supersonic aerodynamics, guidance and control, rocket and jet engines, and aerospace medicine. In missile development, von Braun’s group accelerated the integration of German liquid-propellant rocket technology. But American rocket groups and companies had already formed in World War II—notably Reaction Motors in New Jersey and Aerojet and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California—which meant that the Germans were only one part of a complex story of technological change and adaptation. The driving force in rocket development after World War II, and especially after 1950, was the nuclear arms race. Until Vanguard and Sputnik, space exploration was only a side effect and an afterthought. V-2s and new United States sounding rockets reached into the extreme upper atmosphere and near-space to understand the environment that missiles would travel through.

In sum, Project Paperclip made a significant contribution to American technology, rocket development, military preparedness and, eventually, spaceflight. But there was a moral cost to the program: the coverup of the Nazi records of many of the specialists. In a small number of cases, the United States hosted and integrated people who should have faced war crimes trials. These facts often lead to black-and-white judgments: either the Paperclip scientists and engineers were all Nazi criminals or all technological geniuses. In my assessment, the project and related efforts to seize German knowledge did greatly benefit American science, technology, and national security in the Cold War, but we needed a better filter to screen out some of the worst offenders. In the late forties and early fifties era of anti-Communist anxiety especially, it was all too easy to obscure and excuse their Nazi past. The facts came out only in the 1980s, when their files were declassified. Only then was it possible to make a balanced judgment about Project Paperclip.

Michael J. Neufeld is a Senior Curator in the Space History Department and the author of The Rocket and the Reich and Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War.

Related Topics

Related Objects

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.