Remembering Astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt

Dec 12, 2021

By Emily A. Margolis, and Samantha Thompson

On the evening of December 12, 1921, as 53-year old astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt succumbed to cancer, heavy rains fell from the skies over Cambridge, Massachusetts. After nearly 30 years at the Harvard College Observatory, Leavitt and her stars, hidden by rain clouds, parted ways. Leavitt lived a short but deeply impactful life, during which her achievements failed to receive sufficient recognition. On the centennial of her death, we reflect on her life and legacy.

Leavitt was born in Massachusetts in 1868 and was one of a small group of women in the United States who had the opportunity to attend university. She first enrolled at Oberlin College before transferring to Harvard University’s school for women, later named Radcliffe. There she studied art, philosophy, language, and mathematics. In her final year, she took a course on astronomy at the Harvard College Observatory.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the number of women with college degrees had increased tremendously, but there were still few professional positions available to women with a formal college education and even fewer in the sciences. With a newfound interest in astronomy, and the financial support from her family, Leavitt opted to volunteer as a research assistant at the Harvard College Observatory.

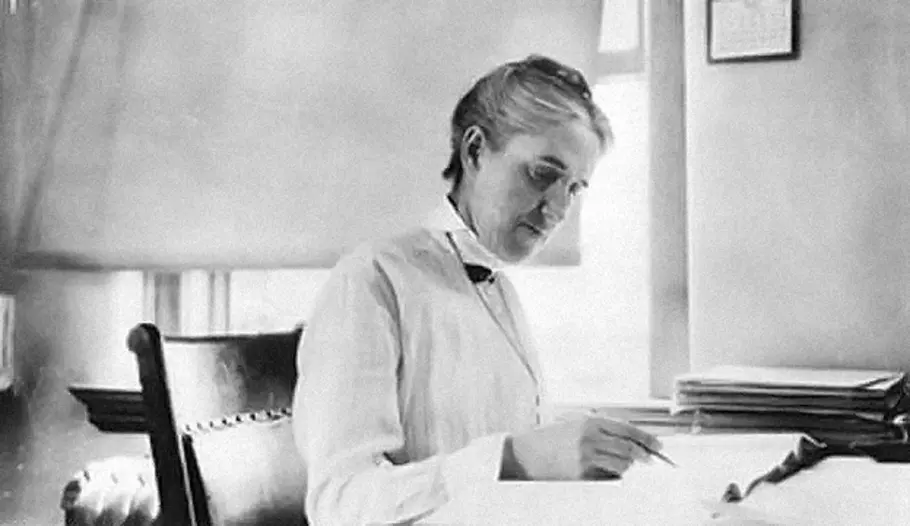

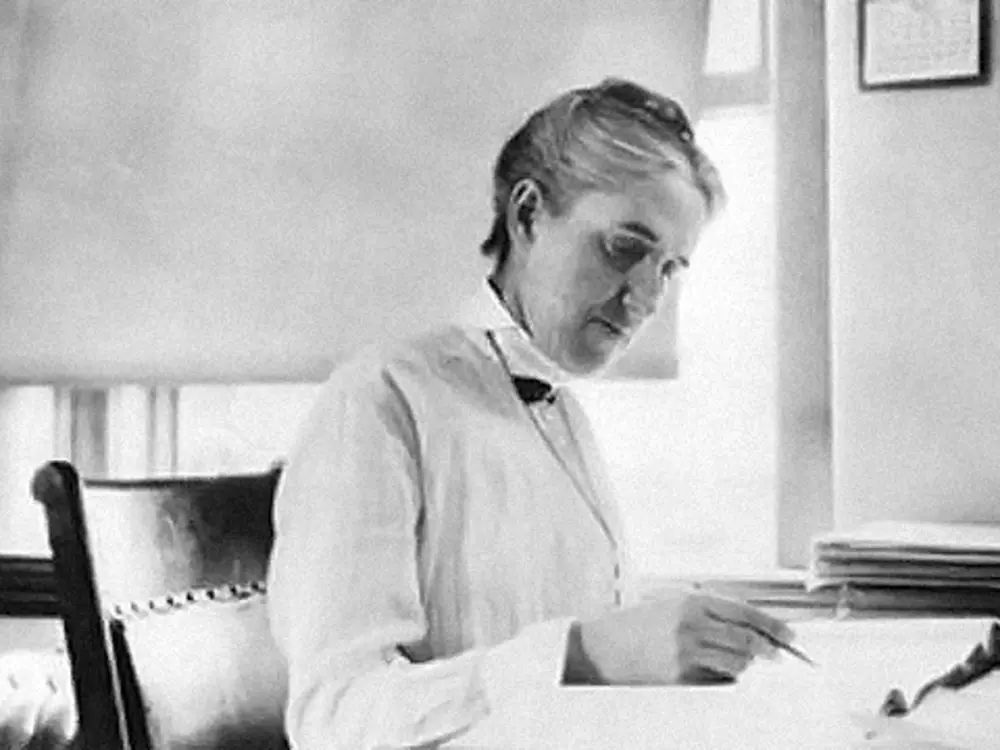

Leavitt working at the Harvard College Observatory. (Image courtesy American Institute of Physics, Emilio Segrè Visual Archives.)

Edward Pickering, the observatory’s director, brought together a group of women to catalog all the stars captured on Harvard’s photographic plate collection. These skilled workers were not allowed to operate telescopes, but they contributed to the analysis of data that led to major scientific discoveries. Some of the women from this group, called “computers,” classified stars by their colors, brightness, and spectra. Pickering assigned Leavitt the task of studying variable stars, a type of star that varies in brightness over time.

Cataloging variable stars was tedious work. Leavitt had to compare pairs of photographs, recorded on plates of glass, taken of the same part of the sky on different nights. She painstakingly examined every star – each photographic plate contained thousands of stars – looking for the smallest change in brightness. Through close observation and sustained attention, Leavitt noticed a significant pattern in the appearance of Cepheid stars, a type of variable star that varies in brightness with a regular “period” (the time it takes for a star to cycle between all levels of brightness).

Leavitt observed that Cepheid stars with long periods were relatively brighter than Cepheid stars with short periods. She determined there was a direct relationship between the period of a star’s dimming and the star’s intrinsic brightness. This meant that if an astronomer could measure the period of any Cepheid star, they could infer its intrinsic brightness. Once a star’s intrinsic brightness is known, astronomers can calculate how far away the star is by knowing how light dims the further it travels. This was quickly recognized as a valuable new tool to measure distances to this class of variable star even when located far from Earth.

Leavitt excelled at examining photographic plates. She was efficient at spotting variable stars on each photograph she analyzed and was skilled in determining their change in brightness. She was unable to engage regularly with this work however, in large part because of continuous health issues, which she suffered from for the majority of her life. At age 17, Leavitt began experiencing hearing loss, which continued to decline throughout her life. She frequently traveled to her parents’ home in Wisconsin where she stayed while recovering from various illnesses. Because Pickering valued her skills so highly, he granted her extended leave and made accommodations so that she could work remotely.

Though Pickering acknowledged and awarded Leavitt for her skills and abilities – she was eventually paid 30 cents per hour, five cents more than most computers – he limited the type of work she could tackle. Few of the women computers were permitted to work independently on questions they may have had about the universe. Though Leavitt wanted to continue her work to understand Cepheid variables, as a computer she had little control over her work and was assigned other tasks. She was not permitted to take up the theoretical work that would have enabled her discovery of the unique property of Cepheid stars to be put into practice. That activity was reserved for the men astronomers that followed her. She died before realizing the full impact of her discovery.

One hundred years after her death, historians, librarians, archivists, authors, and artists recognize and reckon with the devaluation and erasure of Leavitt’s contributions to astronomy. Thanks to the work of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics’ Project PHaEDRA, more people have access to Leavitt’s work than ever before. Authors including Dava Sobel have researched and told Leavitt’s story using these resources, including her astronomical notebooks and glass plates.

Leavitt’s engagement with the glass plates captured the attention of artist Anna Von Mertens, 2021 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow, who explores astronomical themes in her multimedia artwork. From 2018 to 2019, Harvard Radcliffe Institute exhibited Measure, a collection of Von Mertens’ artwork inspired by the life and legacy of Leavitt. The artist mirrors Leavitt’s practice of close observation, sustained attention, and comparison in her own artistic practice of quilt-making.

The stars fading from view on the morning of Henrietta Leavitt’s birth, July 4, 1868, Lancaster, Massachusetts; The stars returning into view on the evening of Henrietta Leavitt’s death, December 12, 1921, Cambridge, Massachusetts. (From the 2018 exhibition Measure, at the Johnson-Kulukundis Family Gallery, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University. Hand-stitched cotton, each panel 100" x 54." Photo by Steward Clements)

Her two-part (or diptych) quilt depicts stars as viewed on the morning of Leavitt’s birth in Lancaster, Massachusetts, and on the evening of her death in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Between these bookends hangs a life about which little is known or remembered. “Historically, quilts have been objects that carry stories through time,” von Mertens explained in her introduction to the Measure exhibition catalog. “They connect generations and allow silent voices to be heard.” Her quilt carries forth Leavitt’s legacy.

Remembrance is also a central theme in the work of Dr. Aura Satz, whose 2014 pieces on Leavitt are part of the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. In the print titled The Leavitt Crater, Satz superimposed Leavitt’s portrait with a photograph of a lunar crater named in her honor. She critiques this commemoration of Leavitt on the topography of the Moon. “The idea of women’s names being associated with imperceptible craters on the moon,” Satz explained in a 2016 interview with Artforum, “seemed an apt metaphor for women having a moment of slight visibility and then receding in the distance of history.”

The Leavitt Crater by Aura Satz, 2014. (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

Leavitt’s legacy shines brighter today than in her lifetime. To learn more about Leavitt and her science, and join the Museum in our effort to bring Leavitt’s contributions to the forefront, explore these Smithsonian Learning Lab collections.

Related Topics

You may also like

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.