Tingmissartoq! Charles and Anne Lindbergh Tour Greenland

Mar 22, 2021

By Dorothy Cochrane

Mar 22, 2021

By Dorothy Cochrane

On August 20, 1933, during a months-long trip to survey commercial air routes, Anne Morrow Lindbergh wrote in her diary, “The last act in Greenland was to have an Eskimo [Inuit] paint “Ting-miss-ar-toq” on the plane. He painted it parallel to the water and not to the lines of the plane.” The name on the nose of the Lindberghs’ Lockheed Sirius has always been intriguing and through the diaries and articles of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, we learn the origin of the name: Native Inuits of Greenland shouted out “Tingmissartoq!” meaning “one who flies like a bird” the moment they sighted this plane.

Levi Imaka painting Tingmissartoq name on the side of the Lockheed Sirius (Image: NAM A-45256-D)

Closeup of the hand painted name on the Lockheed Sirius (NASM Eric Long)

The Lockheed Sirius Tingmissartoq is a well-traveled aircraft that served as the “home” of Charles and Anne Lindbergh during their 1931 and 1933 aerial surveys of potential transoceanic air routes. Since 1976, the plane’s home has been the National Air and Space Museum’s Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight Gallery, now temporarily closed and scheduled to reopen in the future. The transformed gallery will also include the Ryan NYP Spirit of St. Louis in which Charles Lindbergh, in 1927, became the first person to make a solo and nonstop transatlantic flight.

The Lindberghs with their Lockheed Sirius (SI 2002-23710P)

Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark, hosted the Lindberghs for three weeks in the summer of 1933 and one of their stops was the southern town of Julianehaab, now known as Qaqortoq. Dan Ullerup, Director of the Qaqortoq Museum, recently contacted me about their permanent Lindbergh Room, a reconstruction of a room where the couple stayed and the September 2020 release of EUROPA Lindbergh stamps. The Qaqortoq Museum, formerly a Royal Greenland Trading Post, dates to 1804 and is the oldest building in all of South Greenland. In addition, the Sisimiut Museum in Kangerlussuaq, on the west coast, displays a guest book signed by the Lindberghs. Locally popular, the museums will welcome international visitors again when the COVID-19 pandemic abates.

Europa Lindbergh stamps. Charles Lindbergh is on right, next to his wife Anne. (Image courtesy of HipStamp.com, under Fair Use copyright. Credit: Tele-Post Greenland.)

EUROPA stamps are issued by European postal services and emphasize cooperation in the postal sector—with the aim of promoting philately (stamp collecting). The common theme of the 2020 stamps was “old postal routes,” and POST Greenland paid tribute to Charles Lindbergh who became Greenland's first flying postman.

Qaqortoq Museum in Greenland. (Photo credit: Qaqortoq Museum)

The Lindberghs stayed in the pictured 1804 building during their five day visit to Julianehaab, now known as Qaqortoq, in southern Greenland in 1933; it is now the Qaqortoq Museum. Learn more about the Lindbergh Room on the Qaqortoq Museum's Facebook page.

What’s behind the aircraft’s name and the time spent on this cold north Atlantic island? In 1931 and 1933, Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh embarked on two lengthy survey flights over vast expanses of water and uncharted, unpopulated territory, along the “Great Circle,” the shortest distance from North America to Asia and Europe when plotted on a globe. Pan American Airways needed to know if and where airports could be constructed because, at that point, no commercial airliner had the range for nonstop transatlantic or transpacific flights. Charles Lindbergh, Pan Am’s technical director and a veteran Atlantic pilot, undertook the task. However, Charles’ announcement that his wife Anne would accompany him shocked everyone. He knew she was the perfect companion, not only because she was his wife, but because she had earned her pilot license and learned radio procedures, Morse code, and celestial navigation. So, when asked about the potential dangers of the flights for his wife, Charles replied, “But you must remember, she is crew.” In addition, these remote flights offered the couple relief from the endless public scrutiny that had followed Charles Lindbergh since 1927 and, more intensely, after the 1932 kidnapping and murder of their son.

Their 1931 flights surveyed northern Canada, Alaska, and the Soviet Union, and then turned south to Japan and China. For the 1933 trip, the Lindberghs flew to Europe via northeast Canada, Greenland, and Iceland. After visiting many European cities, they flew down the west coast of Africa, across the Atlantic to South America, and back to New York, a trip of 30,000 miles, four continents, and 21 countries. With extraordinary detail, Anne recorded their adventures in her radio logs and diaries. Anne reveled in the remote explorations and was a keen observer of people. While she was truly proud of her award-winning radio work (she set a wireless transmission distance record of 3,000 miles), it is her three literary gems that illuminate the geographic discoveries and the social and cultural aspects of the people they met along the way: “Flying Around the North Atlantic” in National Geographic Magazine, September 1934, and two best-selling books, North to the Orient and Listen! The Wind. Anne also discusses the trip in her autobiography Locked Rooms and Open Doors: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1933-1935. The quotations in this blog are from that published work.

The Lindberghs departed Flushing Bay in New York City on July 9, 1933, arriving in Labrador, Canada, on July 14, and departing on July 22 for Godthaab (Nuuk), Greenland. After sighting high mountains to the east three hours out, they came upon rocky landscapes, fjords, and glaciers, moving Anne to wonder why it was named Greenland. She correctly mused that Norseman Eric the Red was encouraging settlers and discovered it wasn’t just a sales pitch when she spied moss and that the “grass in the gullies looks positively green…” (from Anne’s autobiography Locked Rooms and Open Doors). Brightly painted houses of blue, green, and yellow with contrasting shutters and a dock packed with Greenlanders—Inuits, Danish settlers and those of mixed race heritage—adorned in bright blouses and sealskin pants greeted them on their arrival there and at all of their landing spots. The Lindberghs soaked up the hospitality of all the communities they visited, enjoying singing and dancing presentations, paddling kayaks, and feasting on the local cuisine of fish and vegetables grown in the short Arctic summer. Anne bought her own pair of kamiks, embroidered sealskin boots, also now in our Museum’s collection. A local radio man commended Anne on her work: “When I first heard her touch I knew – here is no ordinary radio operator.”

A pair of sealskin boots owned by an Inuit child

The Lindberghs and Greenlanders in their Sunday best at Godthaab. (Photo credit: Atuagagdliutit)

They departed Godthaab on July 25 at 17:28, a summer evening of extended daylight in this northern land. They first landed in the village of Assaqutaq, south of their intended destination, where a man gave them a note, now considered the first airmail in Greenland, which they then delivered within the hour to the Governor of Holsteinsborg (Sisimiut). A goose arrived by boat the next day from the same man, who noted that he should have sent it by air with the Lindberghs!

For the next 20 days, Charles consulted with the locals about the harbors, terrain, and especially the weather, which also determined each day’s direction of flight. With fog to the south, they flew over Davis Strait to Baffin, Canada, and back. Then they flew north to Christianshaab (Qasigiannguit), Disko Bay, and Jakobshavn (Ilulissat), all the while observing their next major expedition to the east, the forbidding Greenland Ice Cap. Departing Holsteinsborg (Sisimiut) on August 4, Anne already missed her new friend, Mrs. Rasmussen, the governor’s wife.

The locals were apprehensive about the Lindberghs’ flight east over the ice cap, which is the second largest ice sheet on Earth (after Antarctica), but Charles assured them they were well equipped with a sledge, snowshoes, and provisions in the event of a forced landing. En route, Charles cheerily called out to Anne, “Every five minutes [in the air] we save a day’s walk.” Drifting snow and the glacier conspired to obscure a horizon, so Charles wore amber glasses to cut the glare. They landed seven hours later at Ella on the east coast, greeted by Dr. Lauge Koch, a geologist mapping northern Greenland with two planes, two boats, and large ground parties from his base at Eskimonaes, where the Lindberghs would make their northern-most stop. Koch noted the aerial views illuminated the fragility of the territory and its resources: “The arctic is so easy to destroy.”

Flying south, they passed Scoresby Sund (Kangertittivaq) and sighted mountains off to the west not found on any maps—this range was later named for the Lindberghs. They landed between icebergs in the harbor of Angmagssalik (Tasiilaq), a busy town with “more turf houses… howling dogs, more isolated, more primitive.”

Landing amidst icebergs of Angmagssalik (Tasiilaq) harbor. (NASM A-45256-F)

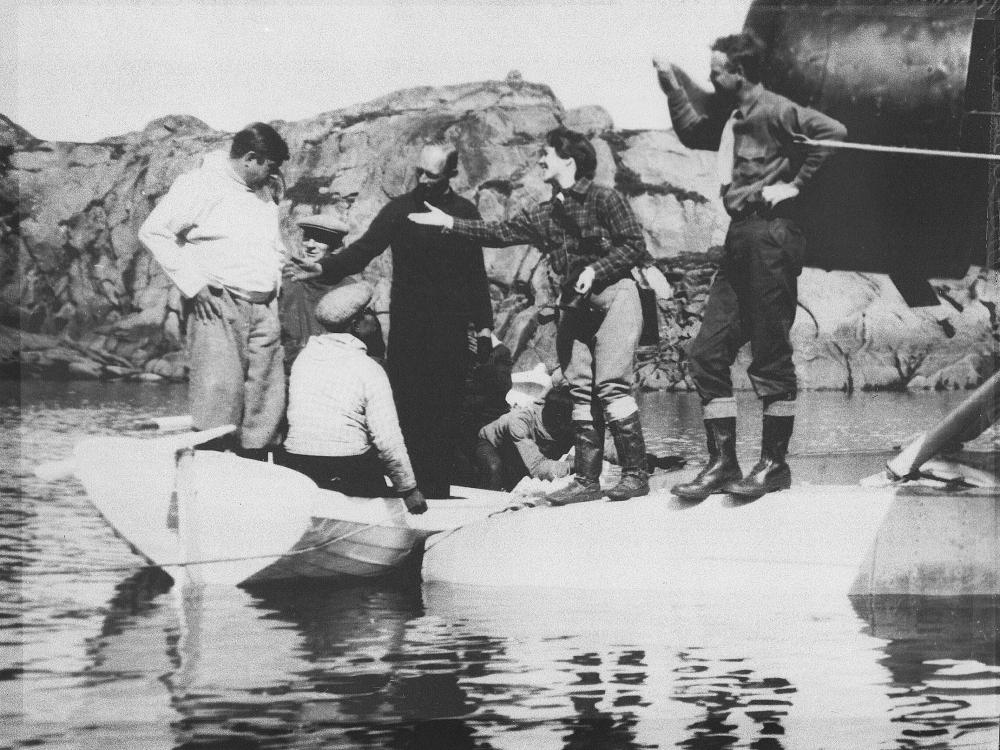

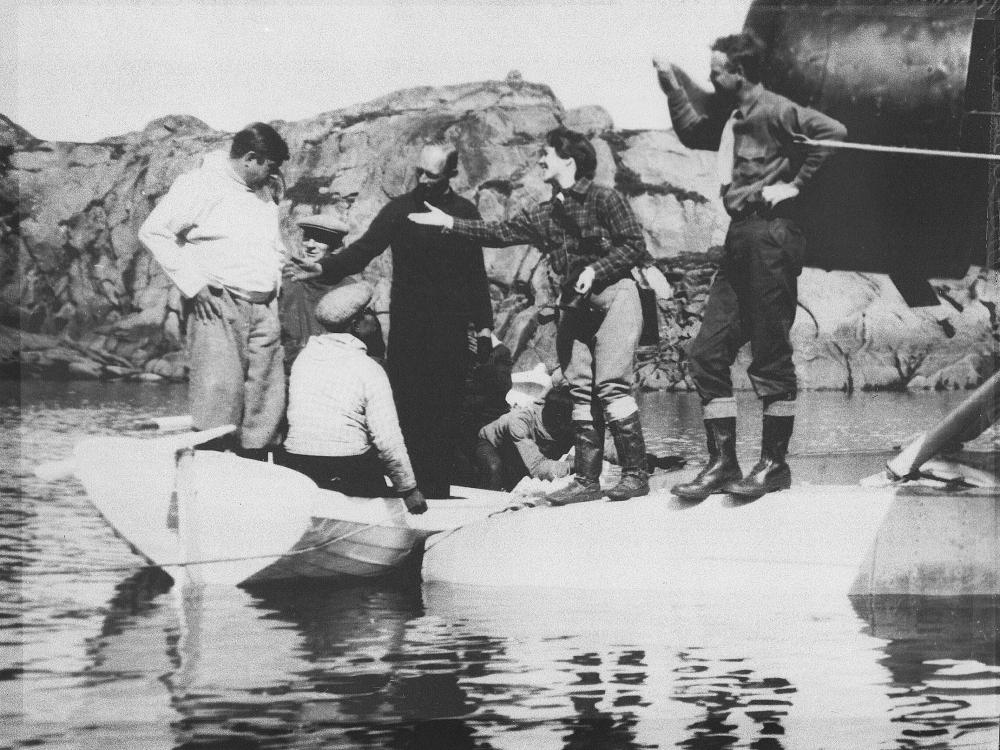

Here they met Knud Rasmussen, a renowned Danish arctic explorer and ethnologist, with his Seventh Thule Expedition mapping crew of surveyors, geologists, botanists, boats, planes, and pilots. “He is a little man and does not look like a hero, completely natural, without conceit, without pose, but a keen strong face. They all love him and call him just “‘Knud,’” Anne reflected.

Arctic explorer Knud Rasmussen (left) meets Anne and Charles Lindbergh (Photo credit: Qaqortoq Museum)

They flew back across the ice cap to Godthaab and then down to Julianehaab, now known as Qaqortoq, which, according to Anne “is perhaps the most prosperous and attractive” town. Today the Qaqortoq Museum also honors Knud Rasmussen with his own exhibit room next to the Lindberghs’.

Upon their return to Angmagssalik, Levi Imaka, an Inuit boy, painted the name Tingmissartoq on each side of the nose of the plane. Several years ago, Museum educator Beth Wilson learned the boy’s name from Greenlanders who also gave her this detail—Tingmissartoq originally meant “one who flies like a big bird,” but Greenland’s language has changed slightly over the years. Today in Greenlandic, an airplane is called “timmisartoq”—so if you’re trying to catch a plane in Greenland, call it a “tim-mi-SAR-torck.”

Anne wrote to her mother, “It is strange but Greenland affects people like an enchanted land. I think it is the intensity of the life, the intensity of one’s impressions, the sharp outlines of the mountains… To say “Ajungilak, tit, ait?” Are you fine or how are you, to a Greenland child and have her smiling back – that is wonderful.”

“Inudluarna Goodby.” The Lindberghs left Greenland the next day, flying to Videy, Iceland, and the rest of their adventures. In his final report, Charles reported that Greenland presented weather and geographical challenges but might sustain some air services, suggesting a Pan Am route from Maine to Labrador to Godthaab (Nuuk) to Iceland, and stopping at or overflying any of these points as conditions and aircraft permitted. In general, the west coast was a narrow ribbon of exposed rocky land while glaciers pushed right into the sea along the east coast. The south had more fog and the interior ice cap was clearer but inhospitable. Pan Am would need to consider planes equipped with pontoons, skis and/or wheels. Summer service along ice-free coastal town harbors and fjords or an airport several miles inland to avoid persistent fog? Flight schedules would depend on the radical swing of sunlight hours from summer to winter. Radio bases would be required for constant weather monitoring until aircraft instrument landing systems became prevalent.

Ultimately, instead of Greenland, Pan American’s first transatlantic Sikorsky flying boats landed in Bermuda in 1937. However, Lindbergh’s Greenland survey flights provided invaluable information for establishing U.S. Army Air Forces bases during World War II and various Great Circle commercial airline routes. Today Greenland’s major airport is Søndre Strømfjord (Kangerlussuaq) Airport, close to one of Lindbergh’s preferred sites inland of Sisimiut (Holsteinsborg); there are 12 other airports and more than 40 heliports. The Qaqortoq and Sisimiut museums highlight this grand adventure, a technical, cultural, and social highpoint for both Charles and Anne Lindbergh and Greenlanders, accomplished in the fittingly named Lockheed Sirius Tingmissartoq.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.