Jun 22, 2022

Many know Orville and Wilbur Wright as the “Wright brothers” – the first people to build and fly a heavier-than-air powered aircraft. The success of the 1903 Wright Flyer is perhaps one of the most iconic stories from American history. But how did Orville and Wilbur Wright end up as pioneering aeronautical engineers? Much of the answer lies in a unique combination of engineering knowledge and skill, creative abilities, and personality traits possessed by the brothers. Even before they got interested in flight, these skills and traits were evident in the business pursuits they took on in the years before they began their groundbreaking aeronautical research.

Technology and innovation were part of the Wright brothers’ lives from childhood. Orville in particular was intrigued by mechanical things as a boy—always building, fixing, and tinkering. He began a printing business as a teenager, and Wilbur soon joined him.

Wright & Wright, Printers

Orville and his boyhood friend Ed Sines had a shared interest in printing. The pair started a small, home-based printing business in 1886 called Sines & Wright in their hometown of Dayton, Ohio. They printed material such as flyers, advertising circulars, letterhead, business cards, and tickets. Following a dispute, Orville bought out Ed Sine’s part of the business, although Sines stayed on to work for him.

Wilbur and Orville’s first formal collaboration was a small printing business they began in the mid-1880s. They did job-printing—flyers, pamphlets, and other small jobs—and published several short-lived newspapers. The close and productive team that would go on to create the first airplane formed during this period.

In 1888, with Wilbur’s help, Orville designed and built a larger, more professional press so he could take on bigger jobs. Among his first contracts was a church pamphlet written by Wilbur, Scenes in the Church Commission During the Last Day of Its Session. It marked the first time the historic reference “the Wright brothers,” appeared in print.

Orville started a local weekly newspaper called West Side News in 1889. After a few issues, Wilbur’s name appeared on the masthead as Editor, with Orville listed as Publisher. The West Side News, which became known as the Evening Item in 1890, faced stiff competition from a dozen other local newspapers. It came to an end after 78 issues, and the brothers decided that doing job-printing only was more profitable.

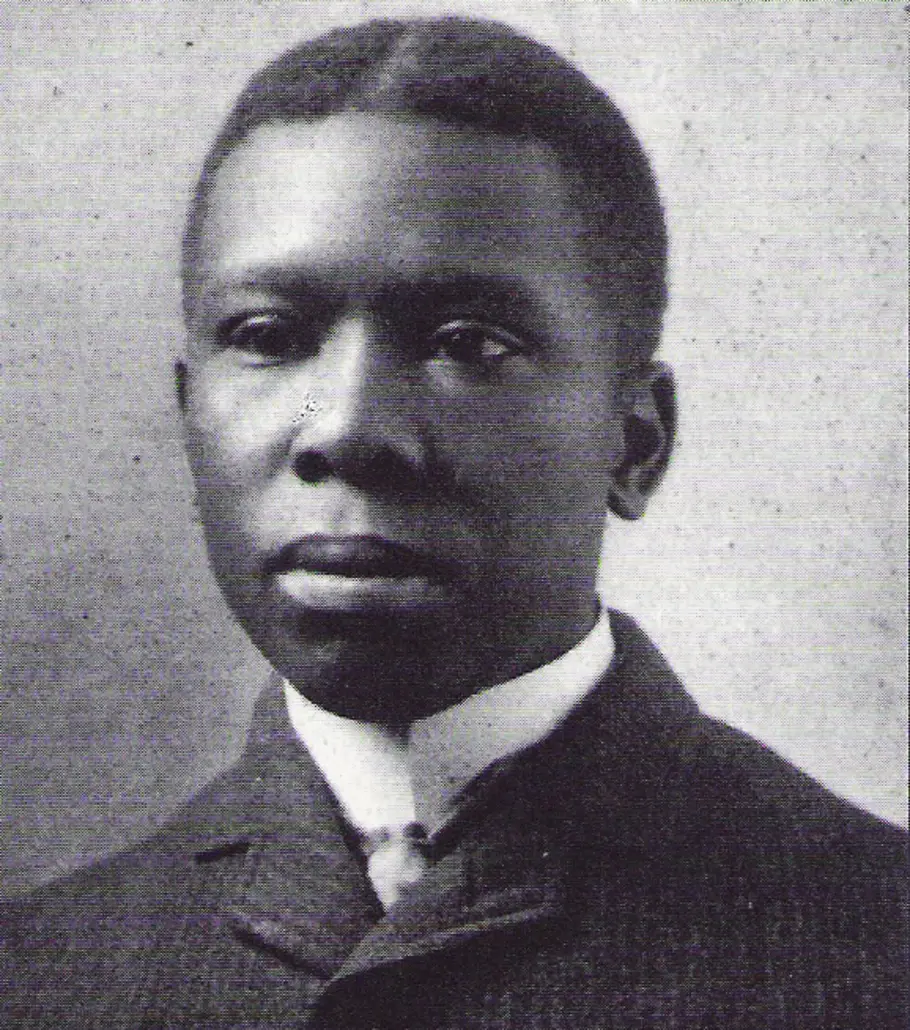

After the Evening Item, the Wrights had one more brief newspaper experience. Orville’s high school classmate, Paul Laurence Dunbar—who later became a famous writer and poet—began the Dayton Tattler, a weekly that was oriented toward the city’s African American community. He hired the Wright brothers to print it, but only three issues were published.

The Wright brothers also published some of Dunbar’s early poetry. This unsigned humorous piece appeared in the last issue of West Side News:

Come, come assist me, trusted Muse!

For I would sing of the West Side News;

A sheet that’s newsy, pure and bright—

Whose editor is Orville Wright;

And by his side another shines

Whom you shall know as Edwin Sines.

Now all will buy this sheet I trust,

And watch out for their April “bust.”

The Wrights sold their printing business in 1899 after Ed Sines, who had been doing most of the day-to-day work by that time, quit.

The Wright Cycle Company

The Wright brothers’ best known pre-aeronautical occupation was building and repairing bicycles. The knowledge and experience gained from working with bicycles proved valuable to the Wrights’ development of a successful airplane. Their bicycle business provided them with a good living, a fine reputation in their local business community, and an outlet for their mechanical interests.

The Wrights opened a shop in response to the bicycle craze in the United States brought on by the introduction of the safety bicycle from England in 1887, which featured two wheels of equal size. They bought their first bicycles in the spring of 1892. Wilbur preferred long country rides, while Orville enjoyed racing and considered himself a “scorcher” on the track.

They began to grow a local reputation as skillful cyclists and mechanics, which led to many requests from friends to fix their bikes. As a result, in 1892, they opened their own shop. While they still owned their printing shop, Ed Sines had been handling most of the day-to-day work, opening up time for the brothers to take on a new challenge—which they found in bicycles.

The brothers quickly expanded their business from rental and repair to a sales shop carrying more than a dozen brands. The Wright Cycle Co. operated in five different locations on the west side of Dayton between 1893 and 1897. However, as competition from other local bike shops began to grow, Wilbur and Orville—once again demonstrating the resourcefulness and enterprise that would spur them to invent the first airplane a little under a decade later—decided to manufacture their own line of bicycles in 1895, and introduced their own model the following year.

While major bicycle manufacturers used new mass production techniques adopted from the firearm and sewing machine industries, the Wrights produced hand-crafted originals. Their advertising emphasized high-quality frame construction and mechanisms and a polished, durable enamel finish.

During their peak production years of 1896 to 1900, Wilbur and Orville built about 300 bicycles and earned $2,000 to $3,000 a year. Only five bicycles made by the Wright brothers are known to still exist.

The brothers moved the Wright Cycle Co. for the last time in 1897, to 1127 West Third Street. It was here they built all their experimental aircraft, including the first powered airplane. Bicycles and airplanes have more in common than one might think, and the Wrights’ familiarity with bicycles contributed to their invention of mechanical flight.

Orville and Wilbur Wrights’ enterprising spirit, evident in their two successful businesses—Wright & Wright, Printers, and the Wright Cycle Co.—demonstrated their innate abilities and drive to succeed when they took on one of humanities biggest challenges: human flight. Many things contributed to the Wrights’ success with flight, but their experience with technology and innovation even before they began studying aeronautics was an essential factor.

This story was adapted from The Wright Brothers & the Invention of the Aerial Age exhibition.

Related Topics

You may also like

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.