A Soviet Moonshot: Interpreting the Diaries of Vasily Mishin

Nov 05, 2021

The beginning of the Space Race was marked by the Soviet Union’s (1922-2001) landmark firsts: the first satellite, the first man and woman and space, and the first spacewalk. From 1958 through 1976, the Soviet Union sent automated explorers that circled, landed on, and roamed about the Moon. Three robotic craft even gathered samples of lunar soil and brought them to Earth. Despite the initial lead in technological advances during this period, it was the United States who was able to land the first person on the Moon in 1969. Moreover, the U.S.S.R. never announced its intent to land a cosmonaut on the Moon.

When the Cold War ended, Space Race era plans for the Soviet Union to send people to the Moon came to light. Diaries, technical documents, and space hardware offered glimpses of the U.S.S.R.'s ambitious crewed lunar program.

So what happened? Why did the Soviet Union suddenly seem to fall behind? The diaries of rocket engineer Vasily Mishin shed some light on why the United States was able to catch up to the Soviet Union's early lead in space.

Vasily Mishin (1917-2001) served as deputy to Sergei Korolëv (1907-1966), who led the USSR into space with the development of the first ICBM and the launch of Sputnik in 1957 at the Experimental Design Bureau, working closely with him on many space projects. Korolëv was head of one of the U.S.S.R.'s missile-development design bureaus. By 1957, his bureau built and launched the R-7, the first operational intercontinental ballistic missile, which was used to propel Sputniks and humans into Earth orbit and Luna spacecraft to the Moon. The USSR secretly adopted a plan to send a human to the Moon in 1964, years after the US had announced the Apollo program. When Korolëv died in 1966, Mishin became Chief Designer and inherited responsibility for the Soviet crewed lunar program.

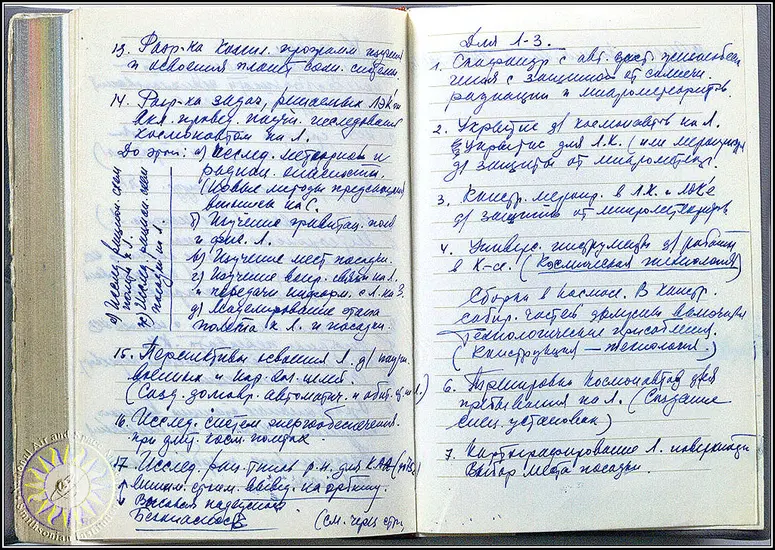

From 1960 to 1974, Mishin kept private diaries detailing the day-to-day workings and decisions of the Soviet space program. The plans and personalities behind this secretive program come alive in these remarkable notebooks.

Soviet Aspirations for a Crewed Lunar Landing

The Soviet Union never officially announced its intentions to land a cosmonaut on the Moon. Mishin's diary entries provide insight into its lunar aspirations that we did not have before.

Failure of a Moon Rocket

Carrying a human and all needed to preserve life to the Moon and back takes a great deal of power. Getting to the Moon required the development of a super-booster, or Moon rocket. When the Space Race began, neither the United States nor the Soviet Union had built a rocket big enough. The US had plans for a super-booster in 1961, but the USSR still had to develop one. By the mid-1960s, Korolëv's design bureau began work on a multipurpose heavy-lift rocket—the N-1.

In July 1969, a test of the N-1 rocket ended in disaster. The rocket shut down seconds after lift-off, fell onto the launch pad, and exploded, destroying the entire launchpad. All four uncrewed flight tests of the N-1 ended in failure. The N-1 program was canceled in 1974, and the Soviet crewed lunar program passed into oblivion. The United States' Saturn V Rocket, on the other hand, successfully met the criteria for a suitable Moon rocket.

How did the Soviet Union lose its early lead in the Space Race and fail to send cosmonauts to the Moon? Since all of the N-1 failures occurred in the 30-engine first stage, Western analysts have speculated that the Soviets were unable to develop a sufficiently powerful and reliable rocket engine in time to beat the United States to the Moon.

Diaries and memoirs of Soviet participants, such as Mishin’s, suggest that other problems also contributed to the N-1 failures. For example, in 1966 Mishin noted several short-comings in the Soviet space program, including problems with the supply of hardware components, absence of a national space agency, the low priority of the crewed lunar program, and lack of a long-term master plan for space exploration.

While it's clear that a major reason the United States was able to land a person on the Moon before the Soviet Union was because of its successful Saturn V Moon rocket, Mishin's diary helps researchers uncover another layer of Cold War history, adding to our understanding of the past and creating a more complete picture of the Space Race.

This story was adapted from the Space Race exhibition.

Related Topics

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.