What's in Your Garage?

Jul 26, 2022

Sports equipment, storage boxes, maybe a bike or even a car—these are all things people typically keep in their garage. However, for many people across the country, if you asked “what’s in your garage?” they might answer with something a little more unexpected: an airplane!

By World War I, factory workers were building airplanes on assembly lines. Because the cost to buy and maintain these aircraft was beyond the means of most people, aviation enthusiasts began to design, build, and fly their own aircraft. Today, thousands of people build sport aircraft from kits or detailed constructions plans. These homebuilt aircraft make general aviation more accessible to those who want to experience the wonder and excitement of flight.

Interest in homebuilt aircraft grew with the introduction of the VariEze (pronounced “very easy”), which was designed by aerospace engineer Burt Rutan. Rutan designed the aircraft to be economical to fly and maintain. The airframe was made of industrial foam covered with fiberglass reinforced with epoxy resin, often called fiberglass-reinforced plastic or FRP. FRP was “very easy” for builders with average skills to work with. Sales took off once Rutan started selling construction plans in 1976. By 1980, two hundred VariEzes were flying in the air.

Closely following Rutan’s plans, builders could construct an airplane powered by a 100 horsepower (75 kilowatt) Continental engine that could carry two adults about 700 miles (about 1,100 kilometers) at 180 mph (290 km/h). Some VariEzes could climb at 2,000 feet (608 meters) per minute to altitudes near 25,000 feet (7,600 meters).

Rutan published a newsletter sharing updates to the VariEze construction plans, corrections, and tips from other builders. The newsletter was called the Canard Pusher. (A canard (French for “duck”) is an airplane with a small wing at the front of the fuselage. Rutan added a canard to the VariEze to give the pilot better control during a stall, when the wings lose lift. Rutan set the canard to stall before the main wing.) Rutan insisted that all VariEze builders subscribe to the Canard Pusher so that they could stay up to date on the latest information about the VariEze. Today, builders of homebuilt aircraft receive this information electronically.

The rise in popularity of the VariEze demonstrated that anyone with average building skills could construct their own airplane—and many did! U.S. Air Force pilot Charlie Precourt was a Space Shuttle commander who docked with the Russian Mir space station. He built his first airplane, a VariEze, in 1978. While Precourt was a professional pilot, he too stood to learn something from building the VariEze: “I was intrigued by the composite [FRP] construction and I thought building it would be useful for my career.”

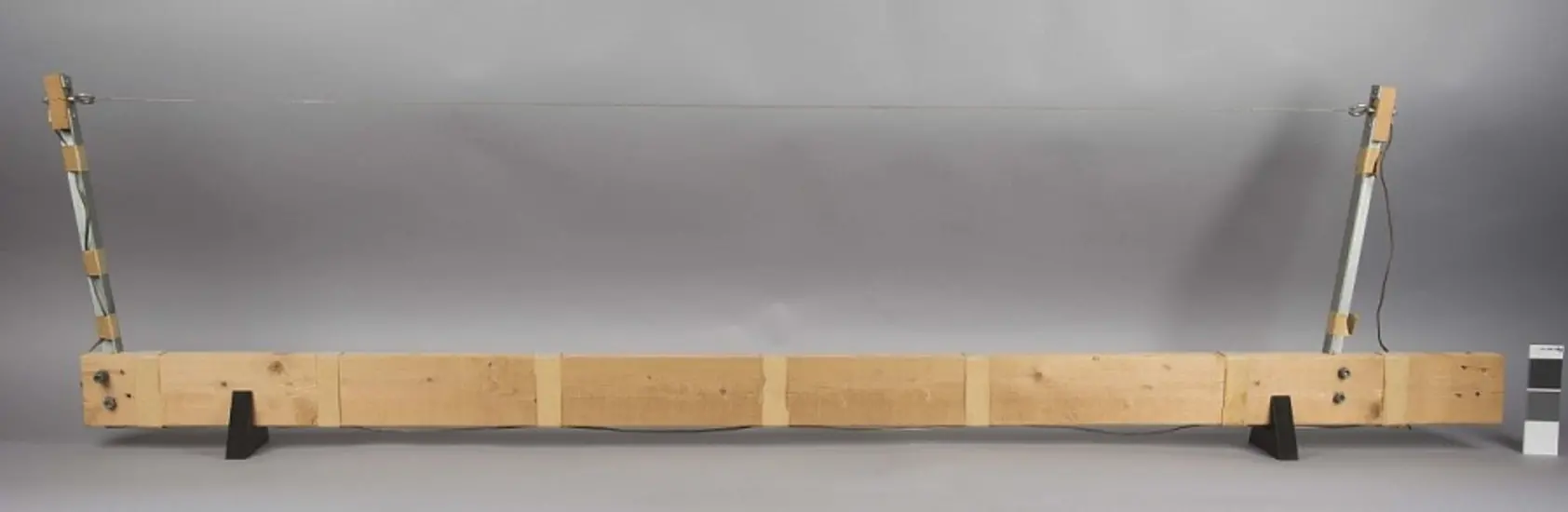

But you don’t need to be an astronaut to build your own homebuilt aircraft. Take a look at some of the steps to building the VariEze below—and who knows—maybe one day when someone asks you “what’s in your garage?” you’ll reply with “my very own homebuilt aircraft!”

Related Topics

Related Objects

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.