What Did It Mean to Be a Flying Ace?

Jul 30, 2025

The term “ace” emerged in World War I to refer to an aviator who shot down five or more enemy aircraft.

French newspapers borrowed terminology from cards and tennis when they anointed one of the first high scoring pilots, Adolphe Pègoud, as l'as (ace). The term stuck. Gunners as well as pilots could achieve ace status.

World War I: The Birth of Military Aviation

World War I was the first time the air was also a battlefield, populated with planes as well as balloons. While balloons were used in earlier wars for aerial observation, pilots in World War I took fighting to the skies.

Armies began World War I using airplanes for reconnaissance. Aviators soon began battling one another to protect their side’s photographic planes, while keeping the enemy's away. The technologies and tactics for aerial combat took time to develop, but by 1916, fighter planes, fighter pilots, and fighter squadrons emerged as a specialized form of military aviation.

Balloon Busting

Balloons used for aerial reconnaissance became targets for enemy planes. Enemy aircraft often fired incendiary bullets that would ignite the balloon’s hydrogen gas. America’s top balloon-busting ace was Medal of Honor recipient Lt. Frank Luke Jr. He shot down 14 balloons before he died in action in 1918. Belgium’s Lt. Willy Coppens gained his fame by downing 35 observation balloons in six months.

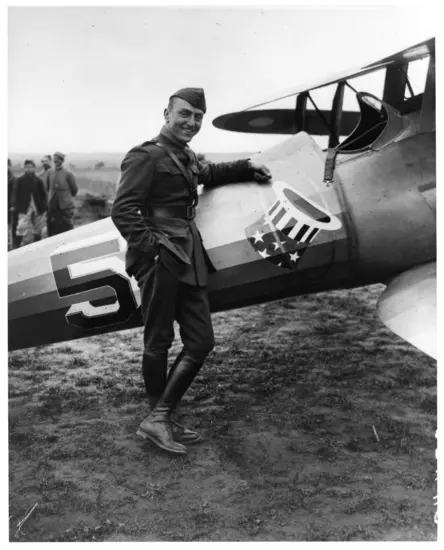

Second Lieutenant Frank Luke Jr. stands with the wreckage of an observation balloon he shot down. The caption that originally ran with the photo reads “Lieutenant Frank Luke, who is running Lieutenant Eddie Rickenbacker a spirited race for the honor of being called the "ACE" of the American fliers overseas. Lieutenant Luke brought down three German observation balloons in thirty five minutes.”

Dogfighting

Initially, planes were mostly used for aerial reconnaissance in World War I. However, that soon changed. Pilots flew pursuit planes (fighter planes) to control the air over battlefields.

Dogfighting refers to the close-range aerial battles that happened between planes. Dogfighting in World War I involved intense maneuvers, including sharp turns, rolls, and extreme dives.

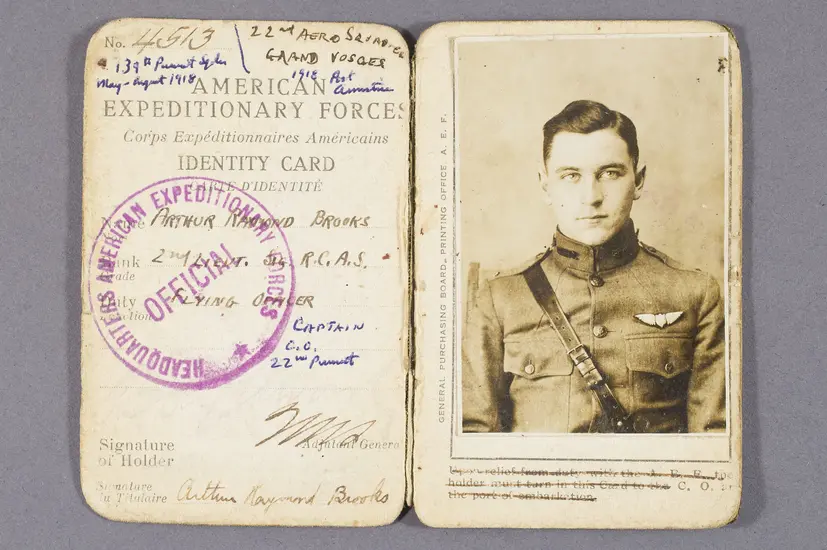

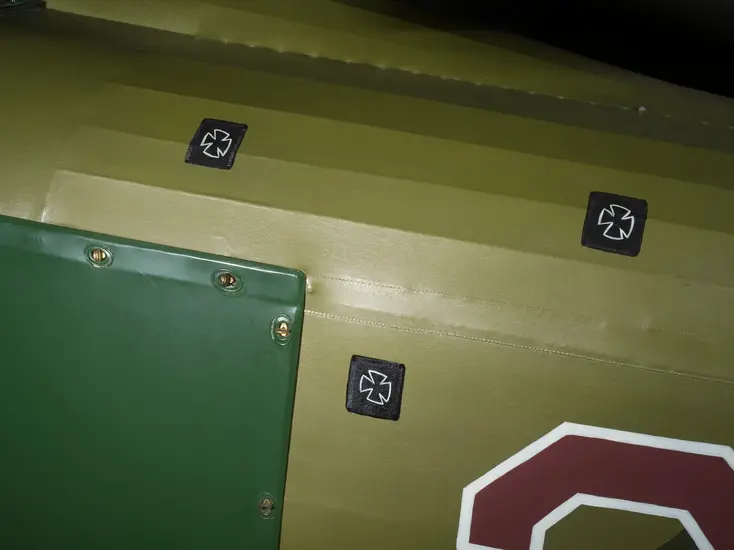

American ace Arthur Raymond Brooks described one dog fight as “the most exciting 10 minutes of his life.” On September 14, 1918, he was attacked by eight German Fokker D.VII fighters after being separated from his formation. Brooks recalled “more darn twisting and crazy positioning than I ever dreamed of doing.” In a logbook entry of the fight, Brooks wrote “Don't know how I got back. 120 bullets in plane, about 5 within 3 or 4 inches from my person.” He shot down two of his eight attackers and received the Distinguished Service Cross for the event.

From the Fokker E.III to the Sopwith Camel, What Aces Flew Made a Difference

When it came to dogfighting, the air was not a level playing field. A challenge for designers was how to design nimble aircraft with a mounted machine gun that could be fired at the enemy without hitting its own propeller. Airplane designers tried multiple configurations to solve this. For example, some aircraft used the pusher formation to mount the machine gun to the front and the engine and propeller behind the behind. However, this arrangement created extra drag.

This was the first aircraft to include a gun in its design. The rear propeller, or “pusher," resulted in reduced performance.

To put a machine gun on the front of the plane, you needed a way not to hit your own propeller. In May 1915, aircraft designer Anthony Fokker solved this by fitting one of his monoplanes with a forward-firing machine gun and the first practical machine gun synchronizer. This devastating combination created the Fokker Eindecker. Fokker pilots shot down so many Allied planes in late 1915 that the period was known by the Allies as the “Fokker Scourge.”

Britain unveiled the Sopwith Camel in mid-1917. The Camel was a versatile front-line fighter whose pilots downed more enemy aircraft than any other Allied plane: 1,294 aircraft. American Camel pilot Elliott White Springs declared the Camel “could fly upside down and could turn inside a stairwell . . . in a dogfight down low nothing could get away from it.” Canadian ace Donald MacLaren alone scored 54 victories, all while flying a Camel.

From Soldier to Celebrity: The Public Image of Flying Aces

Many ace pilots enjoyed celebrity status. Some became national heroes.

Captain Edward V. "Eddie" Rickenbacker was the United States' top scoring flying ace of World War I. Before America entered the war, Rickenbacker was an accomplished racecar driver. Because of his fame, he was offered the position of chauffeur to Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of U.S. forces in France. Soon after arriving in France in 1917, Rickenbacker was captivated by flying and requested a transfer to the fledgling U.S. Army Air Service. Rickenbacker scored 26 confirmed victories.

When Rickenbacker returned to the United States in 1919, there was a party of 600 people in his honor in New York. The Secretary of War himself read a message from General Pershing. New York’s festivities were a preamble to the celebration in Los Angeles which lasted three days, featuring a parade with at least seven bands, a barbeque, and a concert. Rickenbacker was awarded a Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Medal for Merit, and France’s Legion of Honor and Croix de Guerre.

Other aces recoiled from the spotlight that hid the dangerous and terrifying reality of being in the cockpit. For them, the potential cost of war was part of flying. “When I saw the flames touch that German pilot I felt sick for a minute and actually said to myself in horror: ‘There’s a man in that plane.’ Now I realize we can’t be squeamish about killing. After all, we’re nothing but hired assassins,” British ace James McCudden remarked.

Pilots risked their lives every time they flew. According the U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission, “Of the 20 highest scoring aces, 12 were killed in action.” In addition to being the targets of enemy fire, training and accidents could be very dangerous. At some points during the war, more pilots died in training and accidents than in combat.

After World War I Ended, The Title "Ace" Remained

While the term “flying ace” emerged in World War I, it wasn’t limited to the "Great War.” During World War II, thousands of pilots qualified for the title.

oday, aces are far fewer as the ways wars are fought change. However, pilots continue to claim the title. For instance, in 2022 Russia’s Ministry of Defense announced Lt. Col. Ilya Sizov had earned the title for “destroying” 12 Ukrainian aircraft.

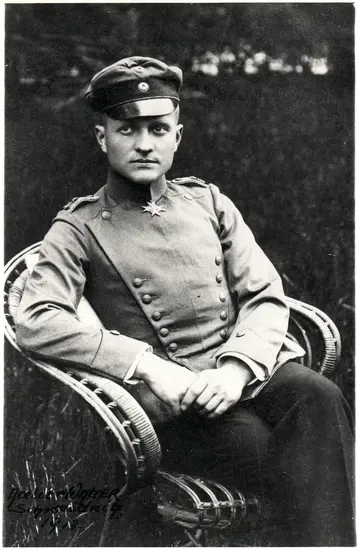

The title of “ace” has endured in popular culture as well. One of the most famous examples is Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. Starting, in 1965, Snoopy imagined himself as a World War I flying ace atop his “Sopwith Camel” doghouse. From comics to toys to games to a Christmas song, Snoopy and the Red Baron have dueled in dogfights for generations. (The real Red Baron is credited with shooting down 80 aircraft, the most of any World War I pilot.)

Of course, behind these pop culture icons are the real people—skilled aviators that fought, killed, and sometimes died in battle.

This story was adapted from the World War I: The Birth of Military Aviation exhibition.

Related Topics

You may also like

Related Objects

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.