Military Reconnaissance

Jump to Content: Balloons Aircraft Satellites

Military reconnaissance is an operation to obtain information relating to the activities, resources, or military forces of a foreign nation or armed group. It uses balloons, aviation, and space technology and has played an important role in our history.

The technologies used to carry out military reconnaissance are varied. From balloon reconnaissance, which the United States military first used in the 1800s during the Civil War, to modern unpiloted aircraft such as the Predator drone, used heavily during conflicts in the Middle East in the late 1900s and early 2000s. On this page, we explore three technologies used for military reconnaissance: balloons, aircraft, and satellites.

Balloon Reconnaissance

More than Just a Map

Civil War Era Balloon Reconnaissance

It is sometimes hard to believe just how much you can learn from some old pieces of paper. While searching in the Archives of the National Air and Space Museum, curator Thomas Paone came across an odd-looking map from the American Civil War. The map features a label in the corner stating that it was drawn by Colonel William Small while onboard “Prof. Lowe’s balloon,” and is dated December 1861.

Who was Colonel Small and how did he find himself drawing a map from a balloon? Why was the map needed in the first place?

From George Washington to Abraham Lincoln, letters in our archives reveal interest from some of the nation’s earliest presidents in ballooning.

During the Civil War, both the Union Army and the Confederacy used balloons. This is the story of one unique balloon.

In this video, experts discuss how balloons were used during the Civil War.

Balloon Basket, United States Army Air Service

World War I Era Balloon Reconnaissance

Armies had experimented with balloons for observation in previous conflicts. In World War I, this technology found a new role. From balloons, observers informed artillery if their shots were on target. This coordination allowed them to operate with increased accuracy.

Military observers for the U.S. Army Air Service watched and photographed enemy troops from balloon baskets like this one. Flying close to the front lines, they reported details to commanders using telephone lines. Observers also noted changes over time, allowing them to see where troops were being staged for a possible attack, or where the enemy was moving supplies, for example. The balloons were tethered to a winch on the ground and usually floated around 1,500 feet (1,000 feet on windier days).

Meet Frank Luke Jr.

The increase in use of balloons during the war also influenced the development of airplanes. The usefulness of observation balloons made them prime targets for airplanes to shoot down. Balloon busters, as these pilots came to be known, became a standard feature of aerial combat in World War I.

Frank Luke Jr. was an American pilot from Phoenix, Arizona, whose short but impressive air combat career made him one of the top “balloon busters” of World War I.

Aircraft Reconnaissance

Early Spies in the Sky

The first major conflict in which photography taken from aircraft was used for military intelligence was World War I. Since then, special cameras, aircraft, and signals technology have been developed to better our military's reconnaissance capabilities. Reconnaissance photography and signals intelligence taken from aircraft and satellites have become an integral tools for the military.

Aerial Photography in Action

D-Day

Aerial photography was combined with code-breaking, spying, French resistance reports, and other intelligence sources to enable the successful execution of a massive invasion two years in the making. D-Day was the boldest, riskiest and most anticipated operation of the entire World War II European Theater. The Museum's Archives contains a small but intriguing batch of aerial photographs taken in the days and hours before, during, and after the D-Day invasion.

Military Reconnaissance and the Cuban Missile Crisis

On October 14, 1962, Maj. Richard Heyser approached the small island of Cuba. He reached into the controls of his U-2 spy plane and flipped on the camera. Heyser was in Cuban airspace for about 6 minutes and took 928 pictures. What those photos revealed triggered a crisis that pushed the world to the brink of nuclear Armageddon.

In the 1950s, reconnaissance specialists needed an aircraft to carry the cameras directly over Soviet territory without risking interception. They found that in the U-2 spy plane—but what they didn't know was that this aircraft would be an integral part of what was to be known as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

On Monday morning, October 15, 1962, CIA photo interpreters (PIs) hovered anxiously over a light table at the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC). The images were just 24 hours old and top secret—taken on a flight over Cuba in a high flying U-2 aircraft. This light table was at the epicenter of this unparalleled national crisis.

The Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird: A Powerhouse in Military Reconnaissance

The Museum's Blackbird accrued about 2,800 hours of flight time during 24 years of active service with the U.S. Air Force.

As the fastest jet aircraft in the world, the SR-71 has an impressive collection of records and history of service.

Walter Watson was the first and only African-American to qualify as a crew member in the SR-71. Hear from this amazing aviator.

Visitors are often surprised to find that SR-71 Blackbird is deeply connected to one of the greatest World War II fighter planes, the P-38 Lightning.

The Museum is fortunate that among our corps of docents, or guides, are people with direct experience flying or flying in a number of our aircraft. Among those docents is Buz Carpenter who knows what it's like to fly in a Blackbird.

In this live chat, hear from Sharon Caples McDougle, who began working with pressure suits for the SR-71 in 1982.

In this episode of STEM in 30, we take a look at the Blackbird's performance and operational achievements that placed it at the pinnacle of aviation technology developments during the Cold War.

A Drone That Transformed Military Combat

The Predator

As an aerospace milestone, the Predator marked several significant transformations underway at the beginning of the 2000s. The Predator can provide near real-time reconnaissance using a satellite data link system and perform attack missions as well. The Museum's Predator was one of the first three UAVs to fly operational missions over Afghanistan after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Satellite Reconnaissance

Development of photoreconnaissance satellites began in the mid-1950s, primarily to target the Soviet Union. They were much less provocative than aircraft overflights and photographed a far larger area.

A highly classified joint Air Force-CIA project, codenamed CORONA, developed the first-generation satellites. Officials assigned the cover name of Discoverer to the program, stating that it was a scientific satellite program. From its first successful mission in August 1960 to May 1972, more than 100 successful CORONA missions acquired critical photography. Among other things, it enabled U.S. officials to learn the numbers and locations of Soviet nuclear-armed missiles and bombers.

Two other photoreconnaissance satellite systems that performed the same missions have also been declassified – GAMBIT (1963-1984) and HEXAGON (1971-1984). All the many other systems remain completely classified.

Ask an Expert

The United States's First Spy Satellite

In early 1958, a few months after the Soviets launched the first Sputnik satellite, President Eisenhower authorized a top-priority reconnaissance satellite project jointly managed by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the U.S. Air Force. The project's goal was to launch into orbit a camera-carrying spacecraft that would take photographs of the Soviet Union and return the film to Earth.

The secret spy satellite was dubbed Corona by the CIA. To disguise its true purpose, it was given the cover name Discoverer and described as a scientific research program. From 1960 to 1972, more than 100 Corona missions took over 800,000 photographs. As cameras and imaging techniques improved, Corona and other high-resolution reconnaissance satellites provided increasingly detailed information to U.S. intelligence analysts.

In this video, listen to curator James David talk about the Corona spy satellite.

GAMBIT-1

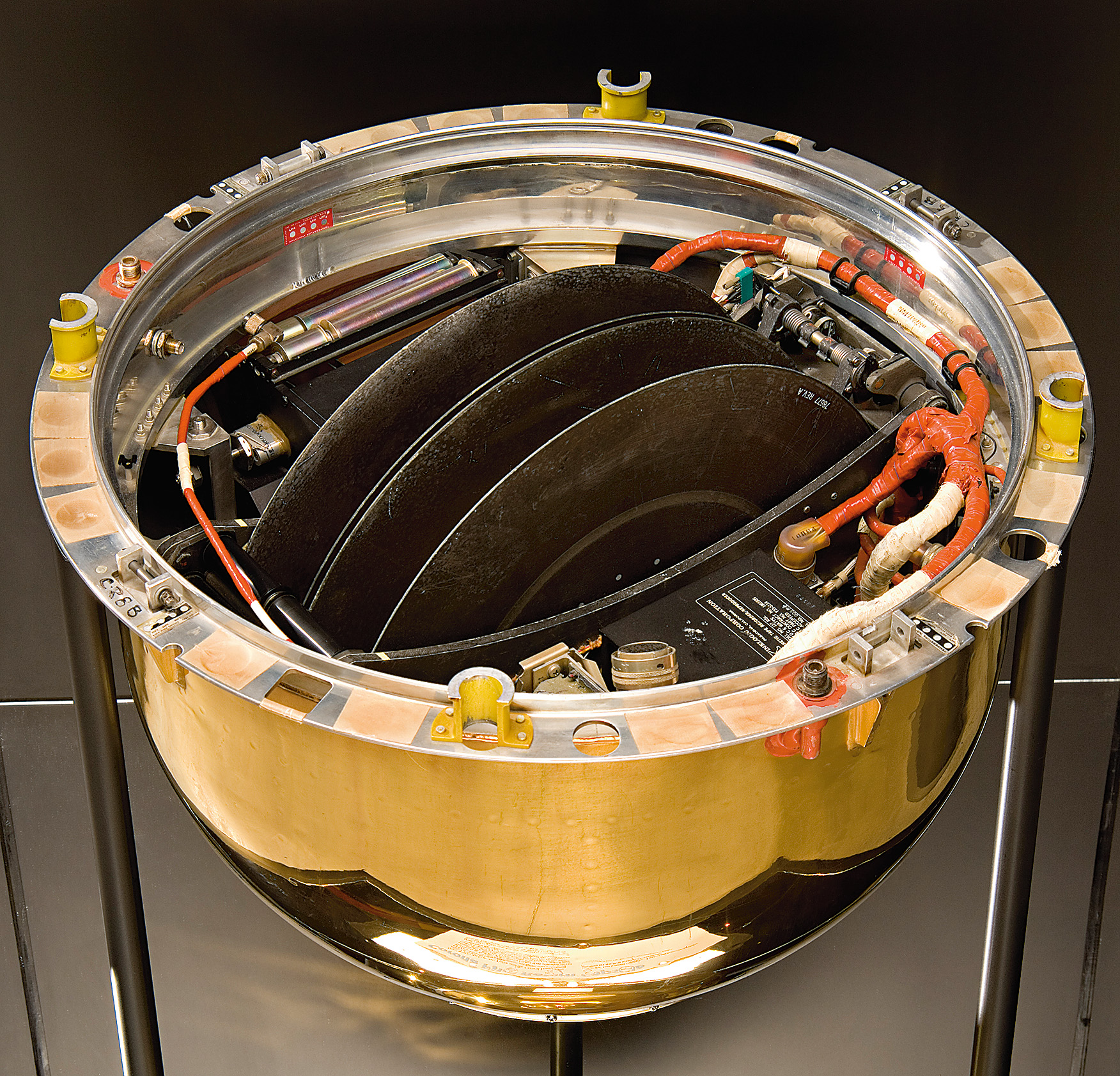

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) launched the first GAMBIT-1 high-resolution photoreconnaissance satellite on July 12, 1963. It enabled the United States intelligence community photo analysts to see more detailed images.

Also in the Collection

Want to keep learning about military reconnaissance? Check out these resources too!

On March 25 1961, in the heart of Soviet Russia, an ejector seat parachuted from a space capsule. Who was this mysterious space traveler?

After decades of unsuccessful attempts to gain access, the public is now finally able to review the President’s Daily Briefs (PDBs) from the Kennedy through Ford administrations. In this story, curator James David as he discusses some of his preliminary findings in the documents.

Quick name some famous spies! Who did you come up with? Jack Ryan? James Bond? Movie spies are fun and resourceful, but real life spies rely on a lot more than fancy gadgets and powerful informants.

People have been spying on each other for forever. This episode is about what changed when spies upped their game (literally), rising into the sky.