Jul 31, 2025

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, into low Earth orbit. This event signaled to many the beginning of a space race between the United States and its Cold War rival. Over the past seven decades, continuing long since the end of the Cold War and the fall of the USSR, many thousands of spacecraft have been launched into orbit. While some of these have carried humans into space, the majority of what has been accomplished in space has been carried out by uncrewed robotic craft. While the first were relatively simple and limited in their automated or robotic functions, over time they have become increasingly complex and capable.

Sputnik, launched by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) on October 4, 1957, marked a simple, yet profound event in history: the placement of the first human-made satellite into Earth orbit.

Consider the case of satellites. Much of how we live on Earth today is facilitated by the nearly seven thousand satellites now operating in orbit. Our orbital infrastructure has evolved alongside the computing and communications technologies we use on the ground. We rely on these space-based assets for the level of connection we’ve come to expect for all of our many devices. They also provide weather and navigational information, as well as imagery, in addition to serving military and national security functions. The satellites nations and companies have put in orbit have built our space infrastructure, but their proliferation has meant that with every new launch, orbital space gets a little more crowded. Many of the previously functional satellites, now dead, remain in orbit taking up valuable space.

One solution to this crowding is to keep the existing satellites in orbit operating for as long as possible, so they can be replaced less frequently. Human astronauts have repaired satellites in orbit, but human missions are costly, not to mention risky. Robotic servicing, repair, and assembly could be a safer option. Companies are working to develop robotic tools that can provide this type of on-orbit work. Northrop Grumman’s Mission Extension Vehicle (MEV) is one example of this—this robotic spacecraft is designed to dock with an aging satellite and take over the functions of its propulsion system, keeping it in a useful orbit while it is still operational. If it is no longer operational, the MEV can also push it out of the way of newer satellites, into a deteriorating orbit where it will burn up safely in the atmosphere. Another robotic tool is the SPace Infrastructure DExterous Robot (SPIDER) arm, developed by MAXAR. This arm is designed to service and repair satellites, as well as to assemble components in orbit.

Beyond Earth orbit, robotic spacecraft are exploring our solar system. The first interplanetary spacecraft was NASA’s Mariner 2, which flew by Venus in 1962. Mariner 2 carried no cameras, but did carry instruments to study the planet’s atmosphere, surface, and magnetic field, as well as the conditions of interplanetary space. As far as space robots go, Mariner 2 was relatively simple. But in the past 60 years the robots we send to the planets have benefited from advances in robotics and computers, and they’ve grown into very capable explorers.

The unmanned Mariner 2 spacecraft began the era of robotic exploration of the planets, moons, asteroids, and comets in our solar system.

Consider the example of Mars rovers. The first rover to successfully operate on Mars was NASA’s Sojourner rover, which landed on the red planet in 1997. This little rover—about the size of a radio-controlled toy car—was delivered to Mars by the Pathfinder lander and spent 95 days exploring the small patch of land around Pathfinder. Like the Soviet Lunokhod lunar rovers that preceded it in the 1970s, Sojourner was able to drive up to rocks on the surface and study them up-close. But even this feat was later surpassed by larger and more sophisticated rovers that drove further, carried more instruments, and returned more data than Sojourner. The Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity, that landed on Mars in 2004, each had a robotic arm loaded with instruments and a tool for scraping the surface of rocks. They spent a combined 20 years exploring Mars and drove several miles to explore different types of terrain.

Three generations of Mars rovers, spanning 15 years (1996-2011), are on view at the Kenneth C. Griffin Exploring the Planets Gallery at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

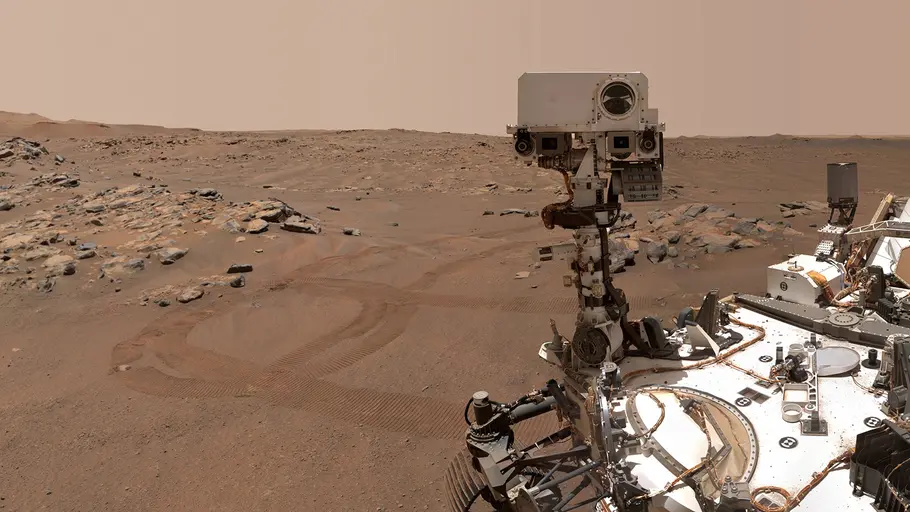

More recently, NASA has sent the compact-car-sized Curiosity and Perseverance rovers (landed in 2012 and 2021 respectively). These rovers have carried more instruments and miniature laboratories with them, have chemically analyzed soil and rock samples, and have even collected samples for later return to Earth. But they haven’t just explored Mars, they’ve also started to pave the way for human exploration of the red planet. The calibration target for Perseverance’s SHERLOC spectrometer instrument includes spacesuit materials that are being tested in the Mars environment. Perseverance also carried the Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment, which demonstrated that oxygen could be separated from the carbon dioxide in Mars’s atmosphere to potentially make breathable air and rocket propellant for human missions.

Close-up "selfie" image of the Perseverance rover. (NASA)

Robots are exploring space and preparing the way for human missions to the Moon and Mars. But their missions won’t end once humans arrive on these other worlds. Whatever humans do in space in the future, robots will almost certainly be there with them. They will be able to perform risky tasks for their human counterparts, work alongside them as helpers, and perhaps even provide companionship. We see this potential imagined in popular culture already. Since even before the first satellites were launched into orbit, science fiction books, comics, and movies imagined intelligent robots who acted as full members of crewed missions. One of the best known and beloved of these robots is R2-D2 from the Star Wars saga. Introduced in the first Star Wars movie in 1977, “Artoo” is a very capable Astromech droid who can perform starship repairs, navigate deep space, carry on lively conversation in beeps and chirps, and fight the Empire alongside his fellow rebels. While our current space robots haven’t yet lived up to R2’s example, each generation is a bit more autonomous than the last.

Home built R2-D2 by Adam Savage, on display at Futures In Space Gallery. Lent by Adam Savage.

Related Topics

You may also like

Related Objects

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.