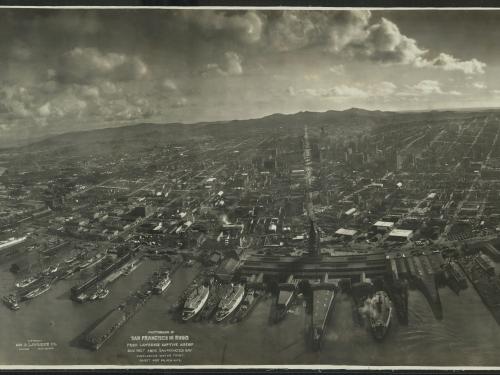

Reconnaissance

While reconnaissance often refers to the collection of information as it relates to military operations, the National Air and Space Museum also offers a large collection of objects and stories connected to aerial observation and observation from space—military or otherwise.

Jump to content:

Deep dives

While reconnaissance often refers to the collection of information as it relates to military operations, the National Air and Space Museum also offers a large collection of objects and stories connected to aerial observation and observation from space—military or otherwise.

Jump to content:

Deep dives

Stories

Exhibitions

Learning Resources

Student

cc-by-nc

Teacher

cc-by-nc

Student

cc-by-nc

Student

cc-by-nc

Student

cc-by-nc

Student

cc-by-nc